Imagine waking up before dawn, knowing your day will be deep underground, surrounded by darkness and danger. This was the daily reality for coal miners.

Their work was not just a job but a grueling battle extracting the coal that powered the industrial age. Let’s delve into the lives of these brave individuals to see their challenges in the early 20th century.

The rise of coal industry early 20th century

At the turn of the 20th century, the coal industry experienced a dramatic rise, fueling the rapid industrialization sweeping across the globe. Coal became the backbone of the industrial revolution, powering factories, trains, and ships.

Coal’s importance skyrocketed as industries grew. Factories used coal to power steam engines, which in turn produced goods at unprecedented rates. Railroads, essential for transporting these goods, also relied heavily on coal.

The demand for coal surged, leading to the expansion of mining operations across the United States, Europe, and other industrializing regions.

The coal industry was a major economic driver. It created millions of jobs, not just in mining but also in related industries such as transportation, steel production, and manufacturing.

Coal mining towns sprang up around rich coal seams, leading to the development of entire communities dependent on coal for their livelihood.

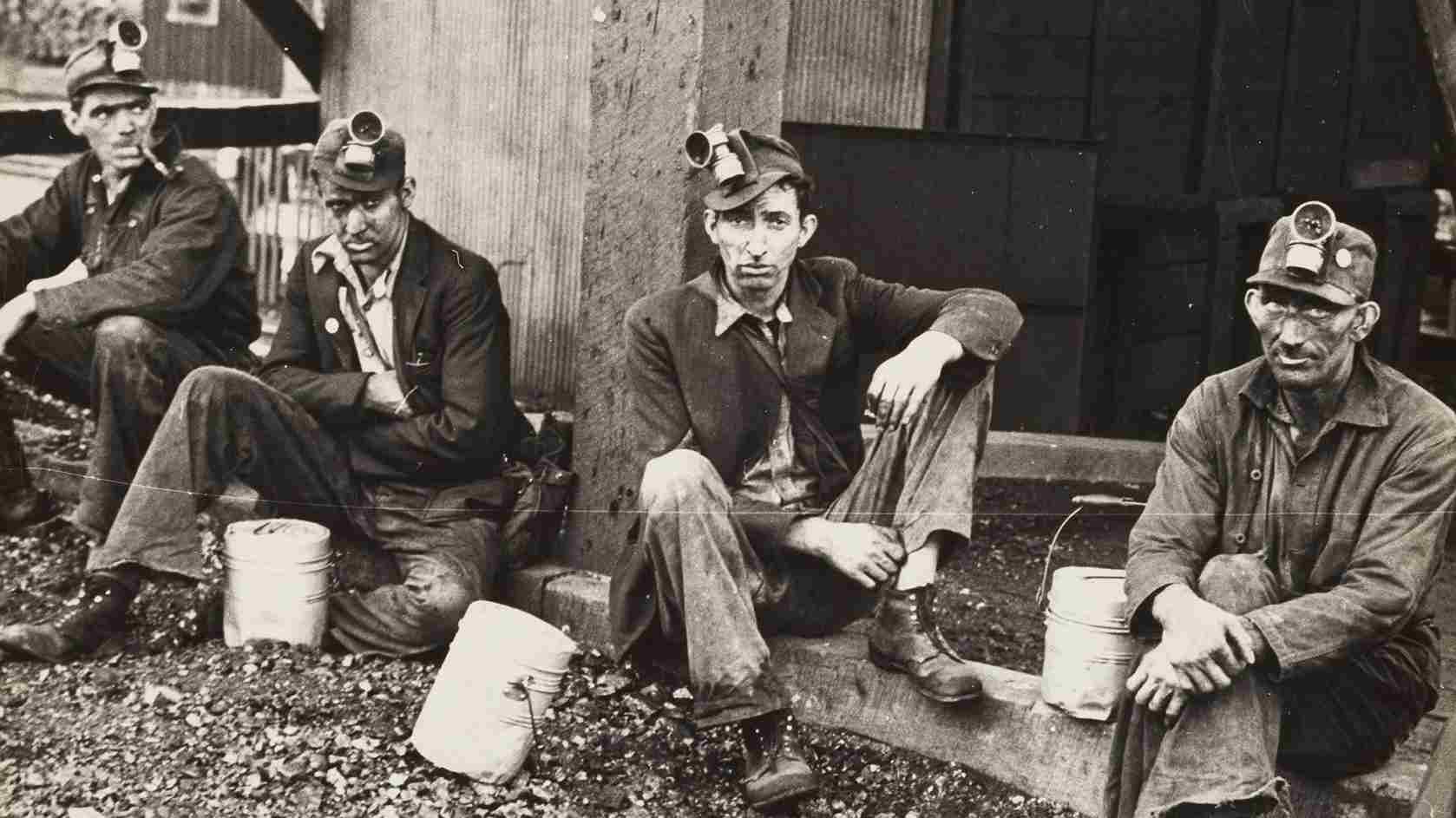

Despite its economic benefits, the rise of the coal industry came with significant challenges. Miners faced harsh working conditions, long hours, and low pay.

The challenges faced by coal miners

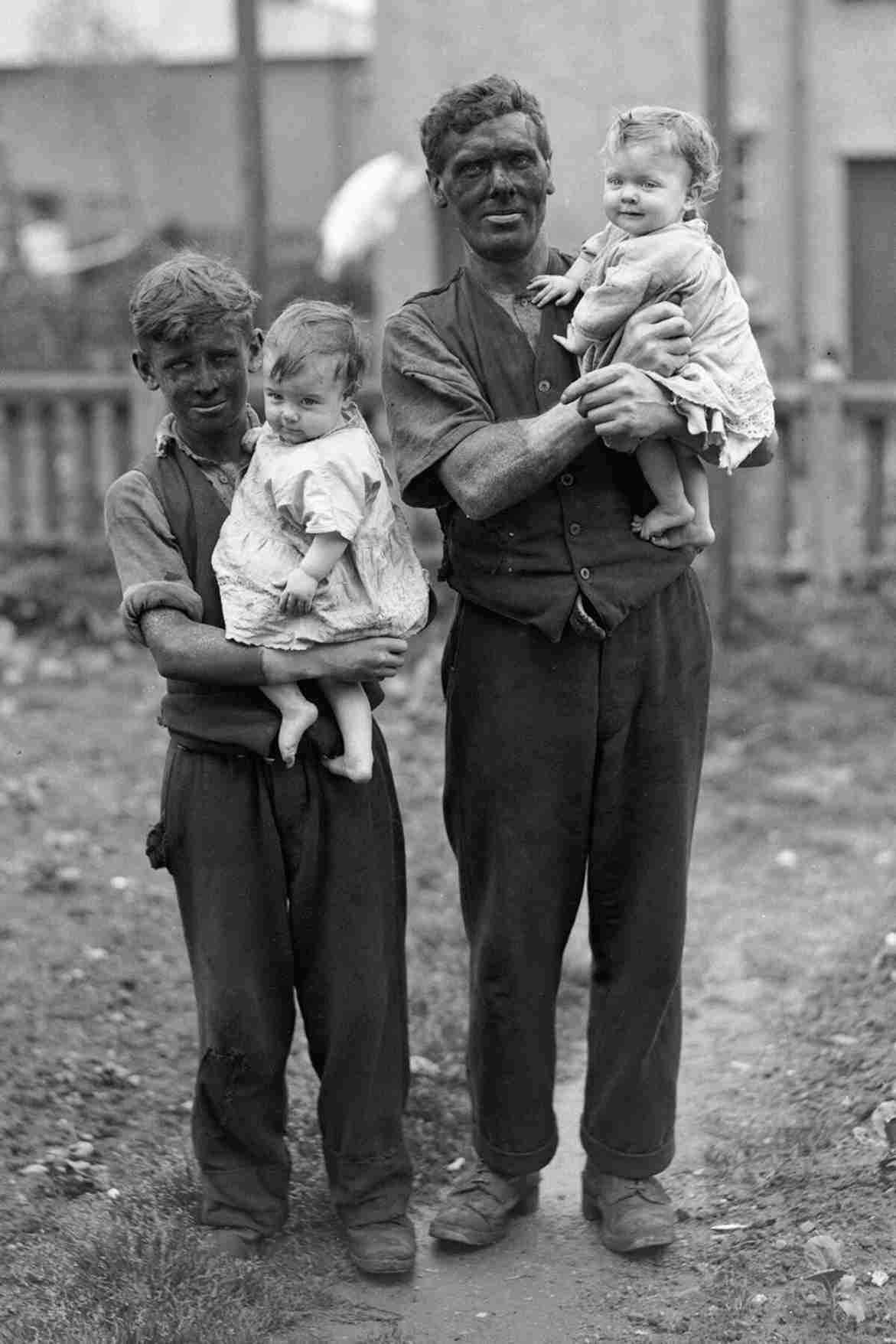

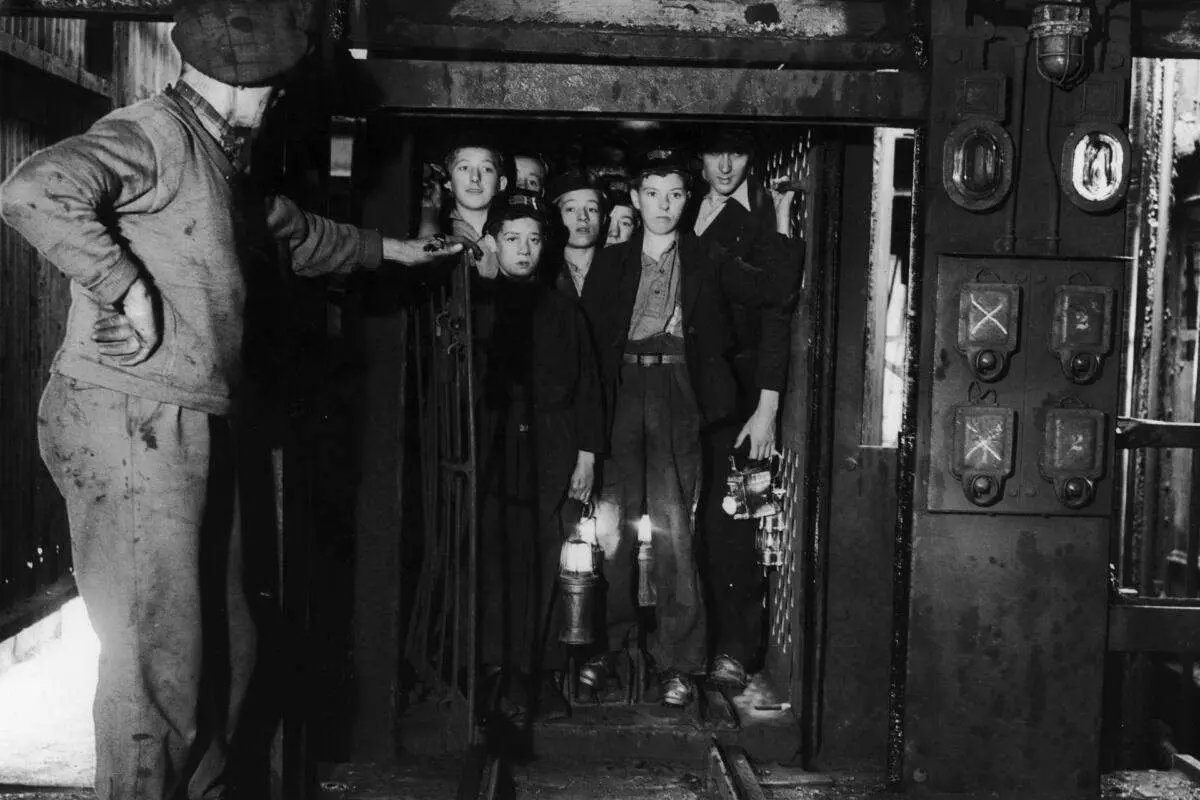

Life was very different for those who powered the Industrial Revolution. Coal mining was often a family affair, with different members doing various jobs in the mines. Men and boys, some as young as nine, went underground, while girls were not allowed to work in the mines.

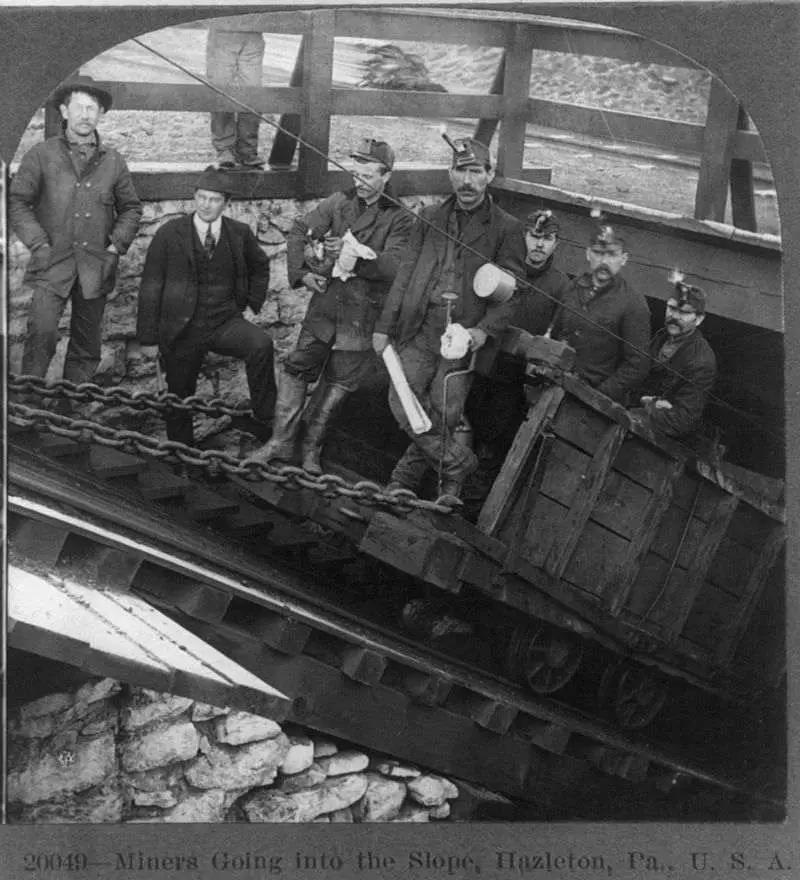

The mining itself was challenging and dangerous. Miners worked long hours, often traveling deep underground by elevator.

Men, called hewers, cut the coal from the seam. Boys worked as putters. After the hewers filled a cart with coal, the putter pushed it to where it could be raised to the surface. They also open and close trap doors in the mine tunnels, improving airflow by directing it to needed areas.

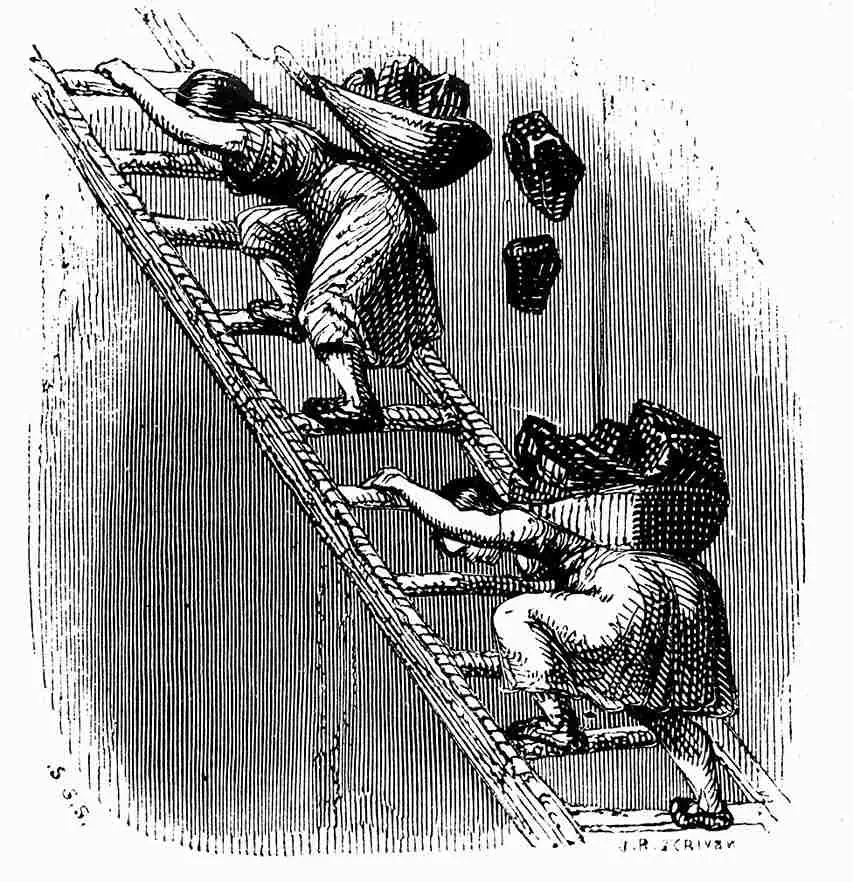

And women, known as bearers, carried or dragged the coal to the surface. Women also managed the financial struggles of their families, using creativity to maintain their homes and feed their families.

Miners rarely made more than a few dollars a week—one 1902 account mentioned a daily salary of $1.60 for a ten-hour shift, equivalent to about $4.50 an hour today.

Much of their money was taken back by the mining company for housing, medical care, and necessities from the company store. Families lived in houses close to the mines, built by pit owners.

The mines were dark, damp, and cramped, with restricted visibility and movement and the constant risk of severe accidents.

The air quality was poor, filled with coal dust that posed significant health risks, leading to conditions like black lung disease. Safety regulations were often ignored, leaving workers to rely on each other against the dangers of mining.

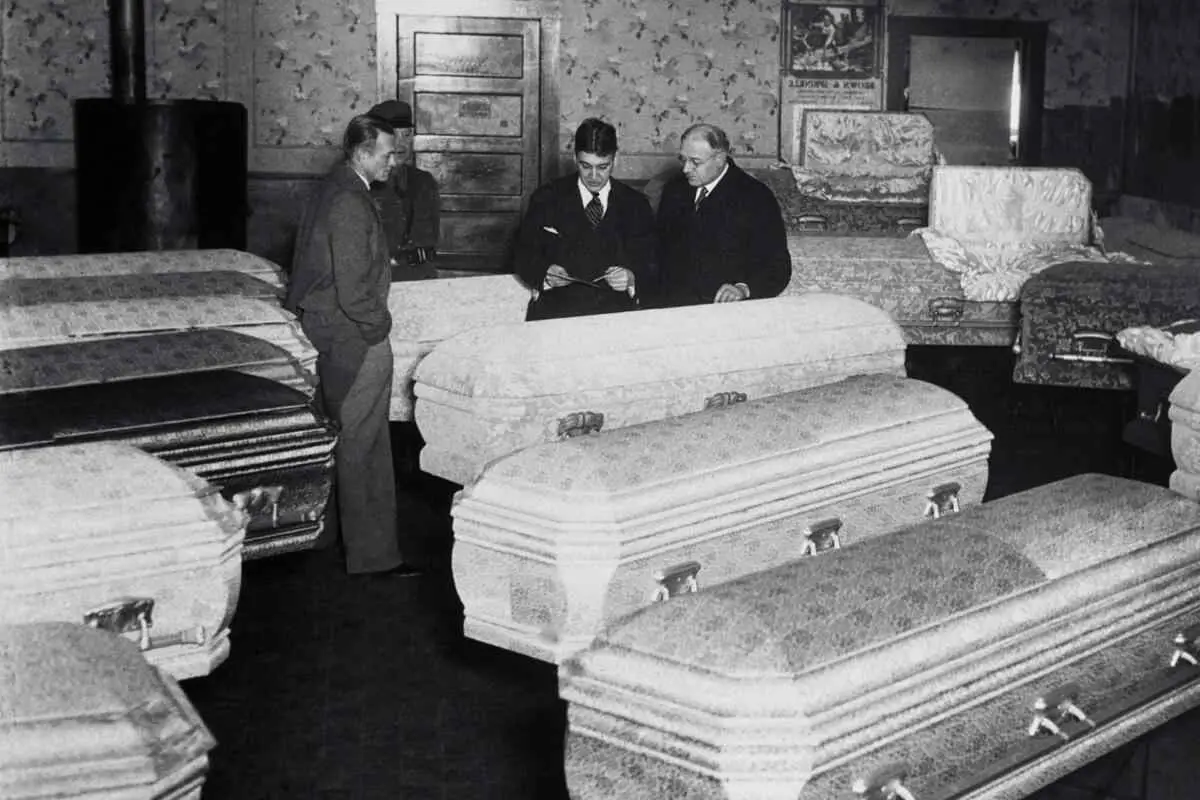

In the early 20th century, hundreds of thousands worked in the mines, and tens of thousands died there because of flooding and gas explosions.

In the mines, without enough clean air, miners could die from choke-damp gases rich in carbon dioxide, which happened frequently in the late previous century. At the New Hartley Colliery in Durham, a mining shaft was blocked by falling machinery.

The 1862 accident led to 204 men and boys dying, some only 10 years old, many from carbon monoxide gas. By the 1890s, miners used canaries to detect deadly gases; if the canaries died, it meant the miners had to leave.

Flooding was a constant threat, with water collecting in tunnels, causing wooden supports to collapse.

As miners dug deeper, the risk increased, sometimes extending tunnels far under the sea. Steam-powered water pumps were used to keep mines dry, but if they failed, the mines could flood quickly.

One notable instance of flooding occurred in 1950 at the Knockshinnoch Castle Colliery in Ayrshire, Scotland. Over 100 miners were trapped underground when an underground lake of liquid peat broke into the mine. Thirteen men died in this disaster.

This incident highlights the constant threat of water in mines, where wooden supports could collapse and cause tunnels to cave in, trapping miners inside.

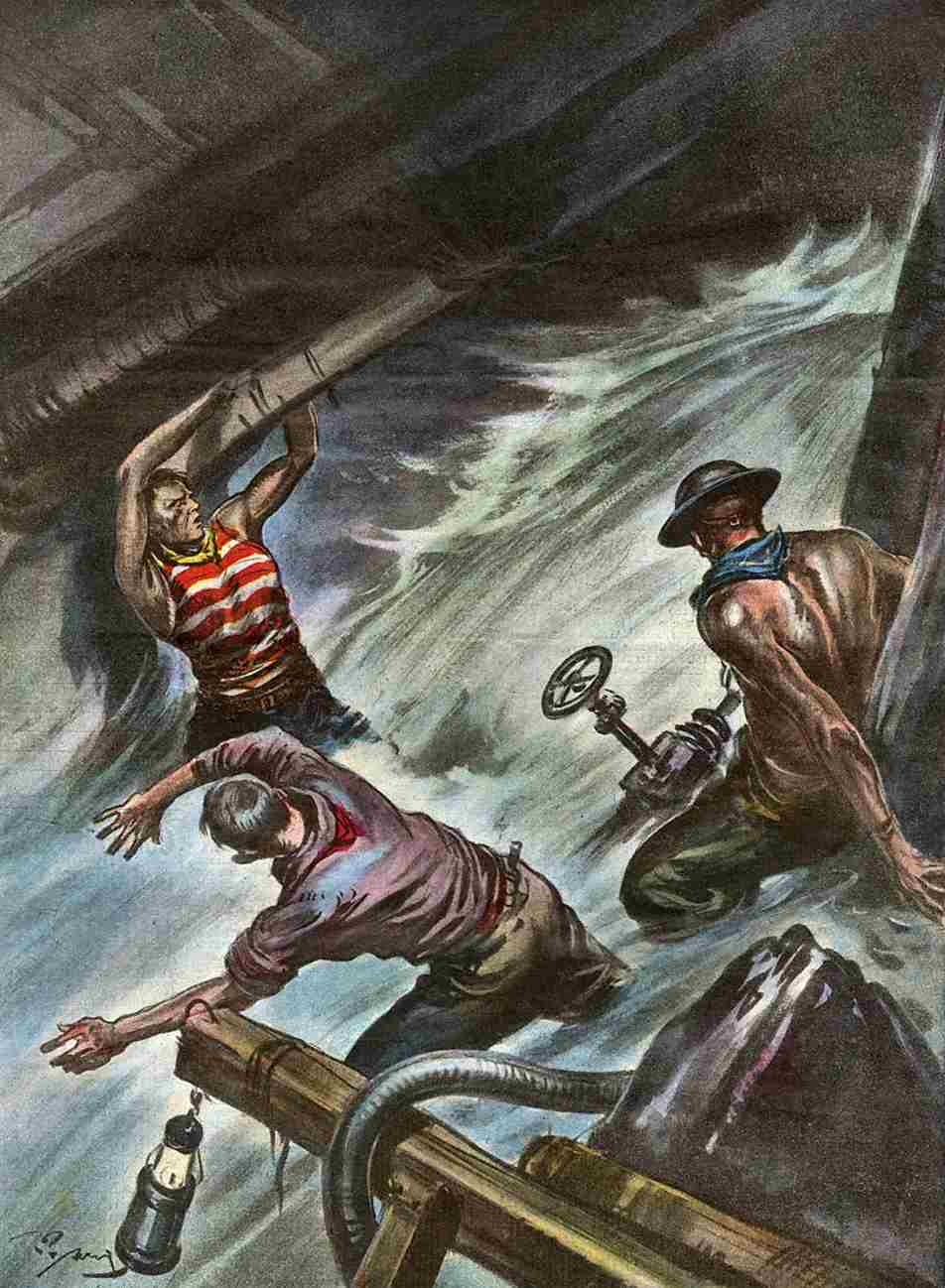

Natural gas was lethal because it might choke workers in a poorly ventilated mine and explode unexpectedly during blasting.

Gas explosions were a frequent and deadly hazard. Methane from coal seams mixed with stale air, forming firedamp, which could ignite and cause fires. This risk was worsened when miners used candles for light.

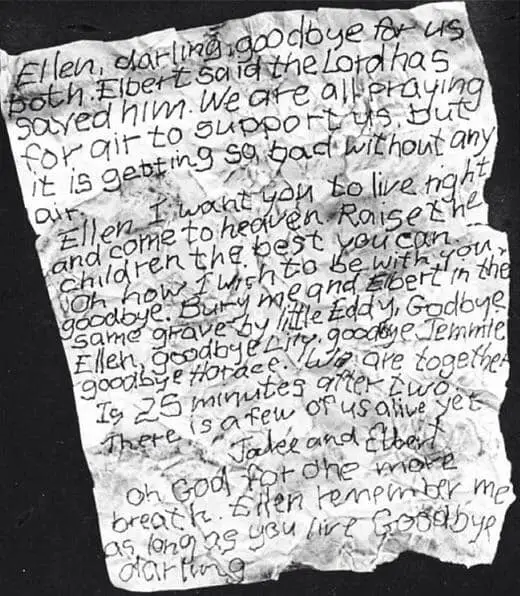

On May 1, 1900, at the Fraterville Mine in Tennessee, an explosion killed 216 miners. Rescue efforts were often delayed due to the presence of choke-damp.

During the explosion, miners trapped underground wrote heartbreaking letters to their loved ones.

One miner, Jacob Vowell, wrote, “Ellen, I want you to live right and come to Heaven. Raise the children the best you can. Oh, how I wish to be with you. Good-bye all of you, good-bye. Oh, God, for one more breath.”

The formation of the labor movement and trade unions

Coal miners who endured low wages and dangerous working conditions for a long time realized they had to unite.

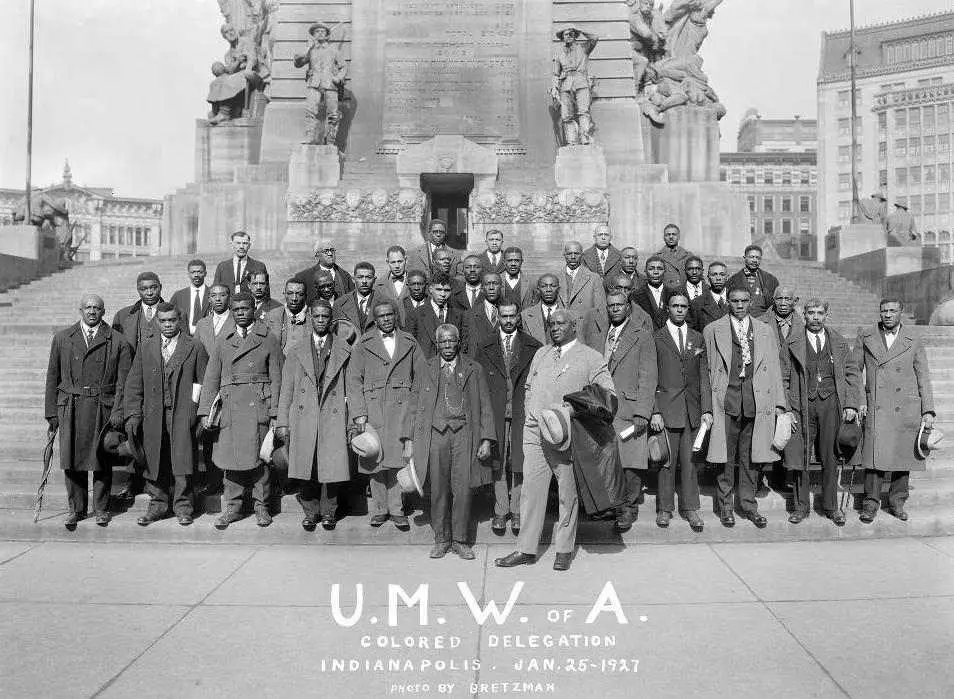

As the labor movement gained momentum, they began organizing themselves into unions to collectively bargain with employers. One of the earliest and most important unions was the United Mine Workers of America (UMWA), founded in 1890.

Labor unions fought for higher wages, increased safety, and better healthcare. However, reforms were often not enforced. Conflicts between unions and mine owners sometimes turned violent, especially in the early 20th century.

Many mines closed due to accidents and decreasing profitability, leading to widespread poverty by the 1930s. While mine safety has improved, gains in healthcare and retirement benefits are threatened when coal companies fail.

According to the Department of Natural Resources, the 185 coal mines employing more than fifty thousand people in 1930 have dwindled to nineteen mines employing fewer than four thousand.