The Eiffel Tower, an iconic symbol of Paris, stands as a testament to human ingenuity and architectural prowess.

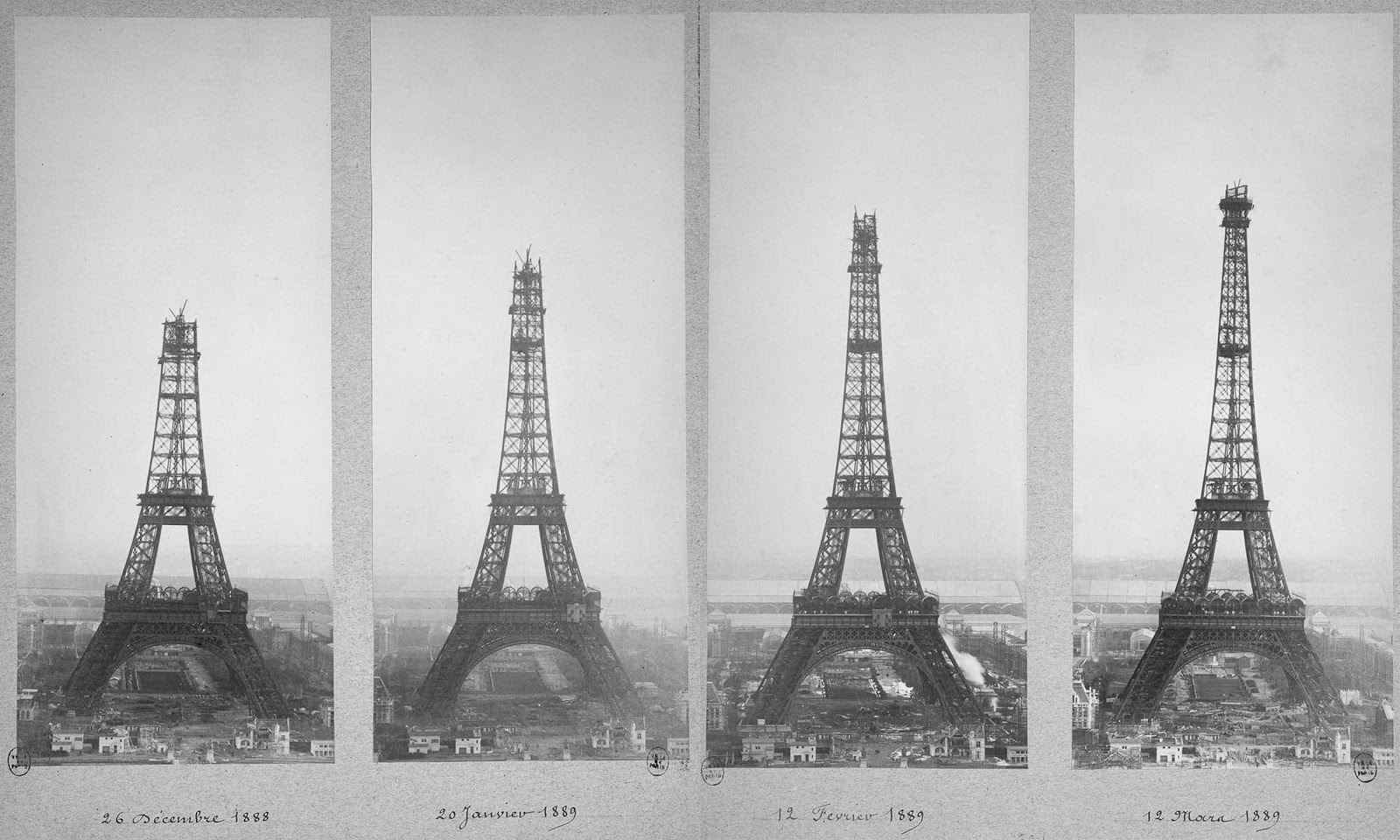

Its construction, spanning from 1887 to 1889, involved groundbreaking design and engineering techniques that captivated the world. Despite initial criticism, the Tower emerged as a beloved landmark, embodying the spirit of innovation.

How did this monumental structure come to be? Keep scrolling down to delve into the remarkable story behind the creation of the Eiffel Tower.

The ingenious design of the Eiffel Tower

In 1889, Paris hosted the World’s Fair to celebrate 100 years since the French Revolution. Over 100 artists submitted plans for a monument on the Champ-de-Mars to serve as the fair’s entrance.

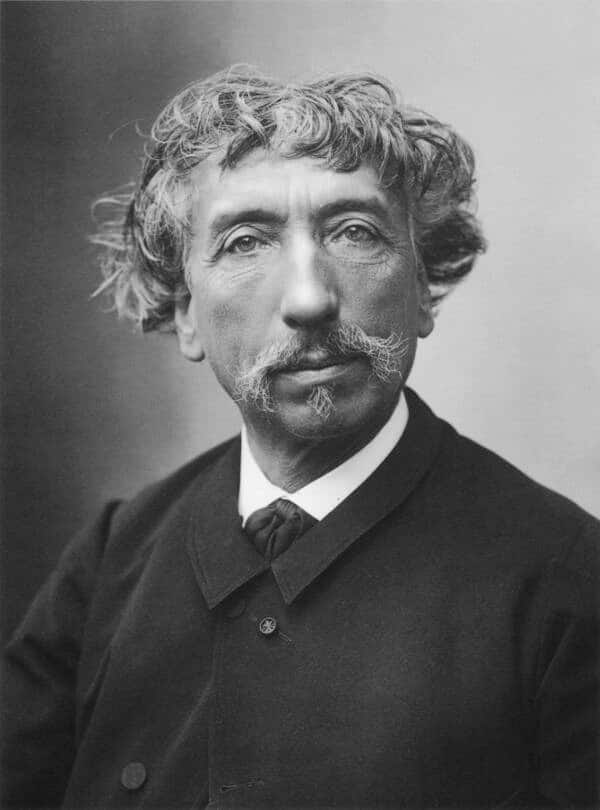

The project was awarded to Eiffel et Compagnie, a firm led by the famous engineer Alexandre-Gustave Eiffel. Though Eiffel gets most of the credit, his employee Maurice Koechlin, a structural engineer, developed and refined the idea.

The plan was to build a 300-meter iron tower. This idea came from Koechlin and Emile Nouguier, the two chief engineers at Eiffel’s company, in June 1884. They envisioned a tall tower with four lattice columns joined by metal girders.

Their design, chosen from 107 proposals, included Eiffel as the entrepreneur, Koechlin and Nouguier as engineers, and architect Stephen Sauvestre. Eiffel patented the design on September 18, 1884, for constructing metal supports over 300 meters high.

To make the project more appealing to the public, Nouguier and Koechlin asked Sauvestre to enhance the tower’s appearance.

A unique first edition of the Eiffel Tower

Sauvestre suggested stone pedestals for the legs, big arches to connect the columns and the first floor, and glass halls on each floor. The top was designed like a lightbulb, and other decorations were added.

The final design was simpler than originally planned, but it kept some key elements like the large arches at the base, which give it a distinctive look.

The curve of the columns was calculated to reduce wind resistance efficiently. According to Eiffel, “All the cutting force of the wind passes into the interior of the leading edge uprights.

Lines drawn tangential to each upright, with the point of each tangent at the same height, will always intersect at a second point, which is exactly the point through which passes the flow resultant from the action of the wind on that part of the tower support situated above the two points in question.

Before coming together at the high pinnacle, the uprights appear to burst out of the ground, and in a way to be shaped by the action of the wind”.

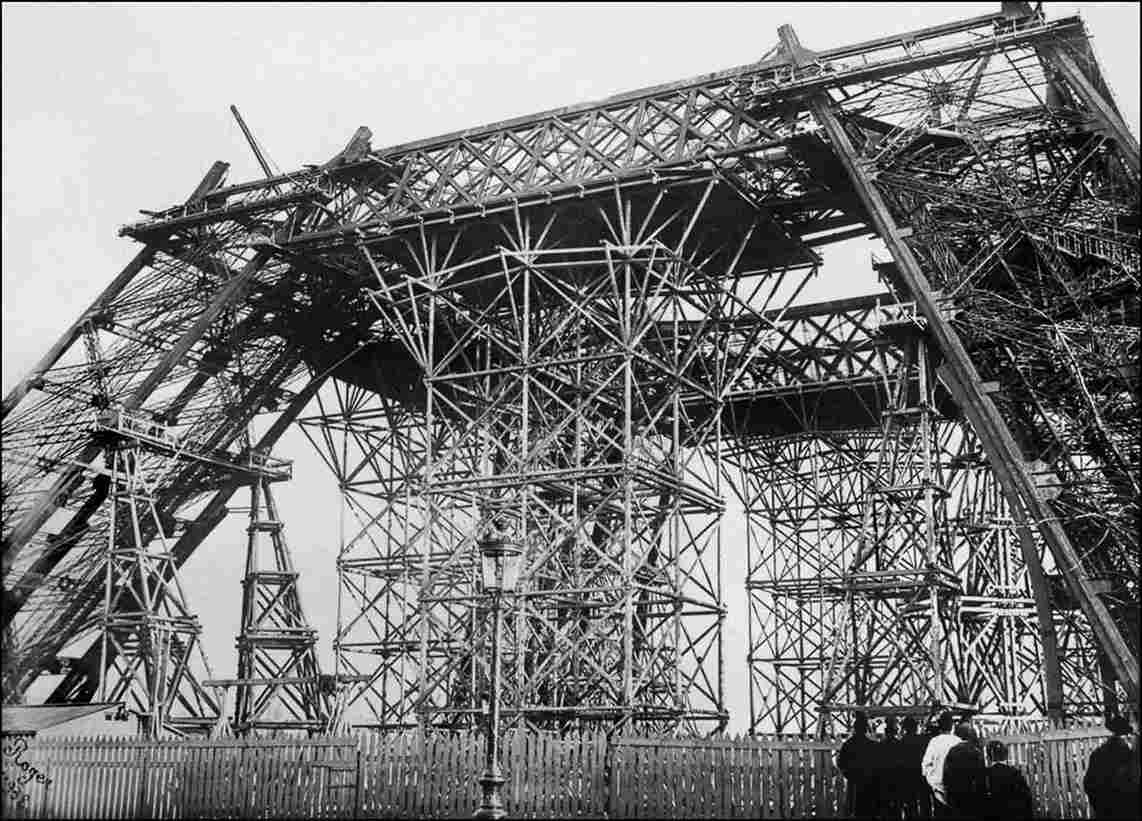

Constructing the iconic tower

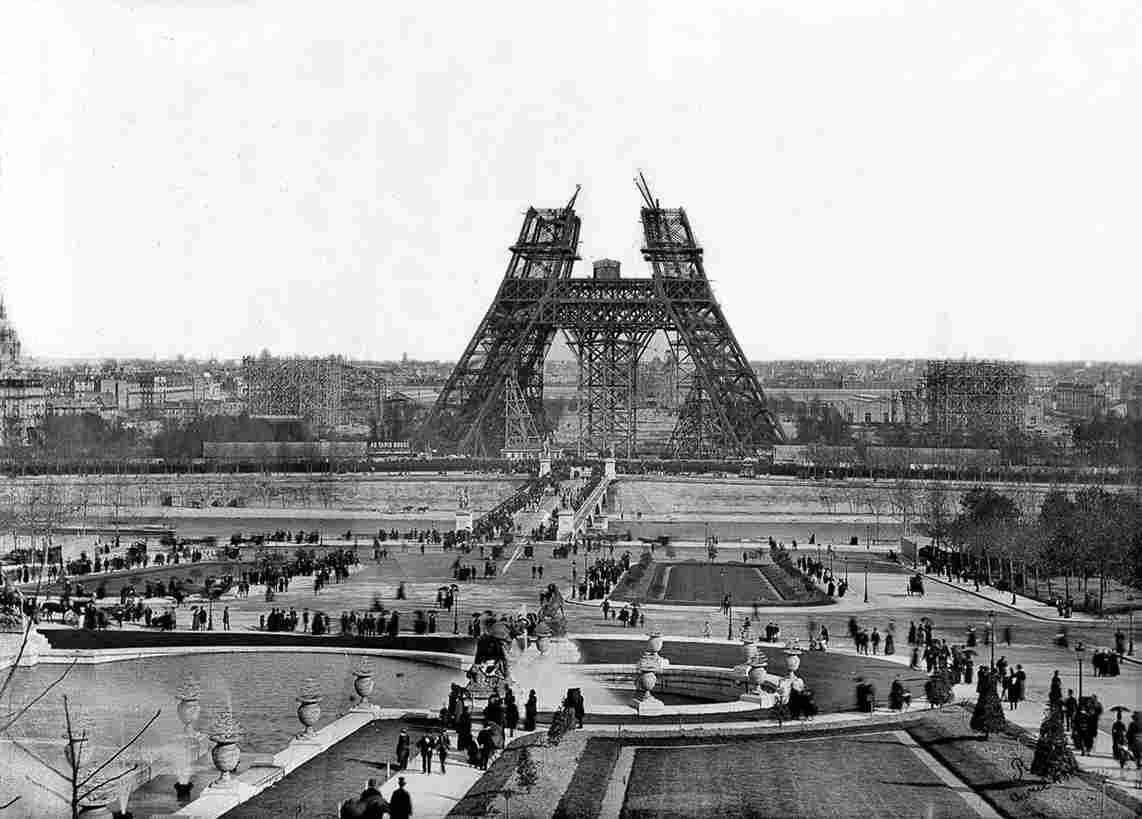

Construction of the supports began on July 1, 1887, and finished 22 months later. All parts were made at Eiffel’s factory in Levallois-Perret near Paris.

The 18,000 pieces used for the Tower were meticulously designed and measured to within a tenth of a millimeter. They were then assembled into sections about five meters long.

A team of 150 to 300 workers, experienced from building large metal viaducts, put the pieces together on-site like a giant erector set.

The Tower’s metal parts are joined with rivets, a refined method at the time. Originally, bolts held the pieces together in the factory, later replaced with rivets that tightened as they cooled.

Four men worked on each rivet: one heated it, another held it, a third shaped its head, and a fourth hammered it into place. Only a third of the 2,500,000 rivets used were put in on-site.

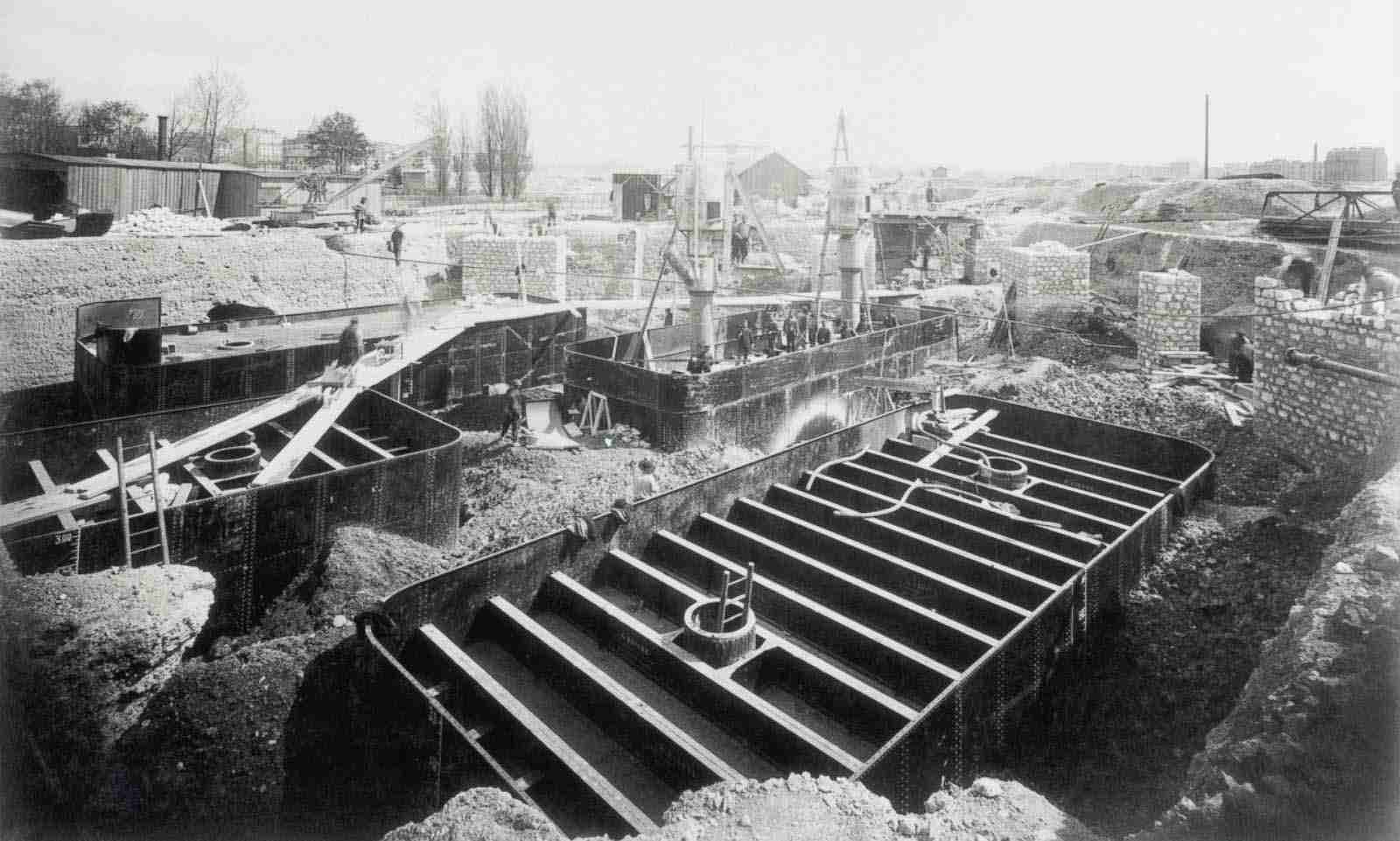

The uprights sit on concrete foundations a few meters underground, supported by compacted gravel. Each corner rests on its own block, with a pressure of 3 to 4 kilograms per square centimeter, and walls connect the blocks.

On the Seine side, builders used airtight metal caissons and compressed air to work below water level.

Wooden scaffolding and small steam cranes on the Tower were used for assembly. The first level was built using twelve temporary scaffolds, each 30 meters tall, and four larger ones at 40 meters.

“Sandbox” molds and hydraulic jacks, later replaced with wedges, positioned girders to within a millimeter.

On March 31, 1889, Eiffel marked the completion by leading officials and the press up the tower’s stairs. At the top, he raised the French flag to the booms of a 25-gun salute.

Though not fully finished, the tower opened to the public nine days after the exposition on May 6. Almost 30,000 visitors climbed its 1,710 steps before elevators were ready on May 26.

It took five months for the foundations and 21 months for the metal pieces. Considering the technology available back then, this was remarkably quick. All historians of that era praised the Tower’s assembly for its precision.

Debate and controversy surrounding the Eiffel Tower

During and after the World’s Fair, millions of visitors marveled at Paris’ new architectural wonder, the Eiffel Tower. However, not all Parisians shared the enthusiasm.

Even before it was finished, the Tower sparked heated debates. It faced criticism from prominent figures in art and literature, yet it stood its ground and eventually gained the recognition it deserved.

Guy de Maupassant, a French author, famously called it “a diabolic undertaking of a boilermaker with delusions of grandeur.” His disdain persisted even after its completion, joking that he dined there because it was the only place in Paris where he didn’t have to see it.

Other critics were even harsher in their descriptions of the Tower: Léon Bloy called it “a truly tragic street lamp,” Paul Verlaine likened it to “a belfry skeleton,”

François Coppée described it as “a mast of iron gymnasium apparatus, incomplete, confused, and deformed,” while Maupassant mocked it as “a high and skinny pyramid of iron ladders, an ungainly skeleton sitting on a base that seems fit for a colossal monument but ends up looking like a thin factory chimney.”

Joris-Karl Huysmans referred to it as “a half-built factory pipe, a carcass waiting for stone or brick, a funnel-shaped grill, or a hole-riddled suppository.”

Initially planned for demolition after 20 years, the Tower’s value for communication spared it. By the time it was completed, criticism had faded in the face of its popularity.

Gustave Eiffel defended it as a monumental achievement, likening its dismissal to disregarding the ancient pyramids.