If you’ve ever attended a U.S. sporting event, you know the routine: people stand, place their hands over their hearts, men remove their hats, soldiers salute, and sometimes jets soar overhead. Then, the crowd belts out, “O say can you see…”

Many mumble through the rest. A recent poll shows two-thirds of Americans don’t know the first verse of their anthem. However, if people knew the incredible history of the flag that inspired this song, they might find it easier to remember.

That iconic flag, commissioned by Major George Armistead for Fort McHenry during the War of 1812, sparked the poem that later became our beloved national anthem. Let’s delve into the captivating story behind “The Star-Spangled Banner” flag.

The creation of the flag

In the summer of 1813, Major George Armistead, the commander of Fort McHenry, knew his fort was a likely British target and wanted a flag so large that the British couldn’t miss it.

He said, “We, sir, are ready at Fort McHenry to defend Baltimore against invading by the enemy … except that we have no suitable ensign to display over the Star Fort, and it is my desire to have a flag so large that the British will have no difficulty seeing it from a distance.”

He hired Mary Young Pickersgill, a 37-year-old widow and professional flagmaker, to create a 30-by-42-foot flag with 15 stars and 15 stripes, representing the 15 states at the time.

Pickersgill, her family, and an indentured servant used 300 yards of English wool and cotton for the stars. They started in Pickersgill’s home but later moved to a brewery for more space. The flag was delivered to Fort McHenry on August 19, 1813.

Pickersgill was paid $405.90 for the large flag and another $168.54 for a smaller storm flag. It was the storm flag that flew during the battle, while the large flag was raised on the morning of September 14, 1814.

The Second Flag Act of 1794 required 15 stars and stripes to represent Vermont and Kentucky. The Third Flag Act of 1818 reduced the stripes to 13 and set the stars to match the number of states.

Armistead remained in command of Fort McHenry until his death in 1818. Historians aren’t sure how his family got the flag, but his wife Louisa inherited it. She likely added a red “V” or an “A” to honor Armistead.

Louisa started the tradition of giving pieces of the flag to remember her husband and the soldiers. When she died in 1861, the flag went to her daughter, Georgiana Armistead Appleton, despite legal objections from her son.

During her tenure as a textile conservator at NMAH in 2007, Suzanne Thomassen-Krauss stated that “Georgiana was the only child born at the fort, and she was named for her father; Louisa wanted Georgiana to have it.”

The tradition of distributing pieces

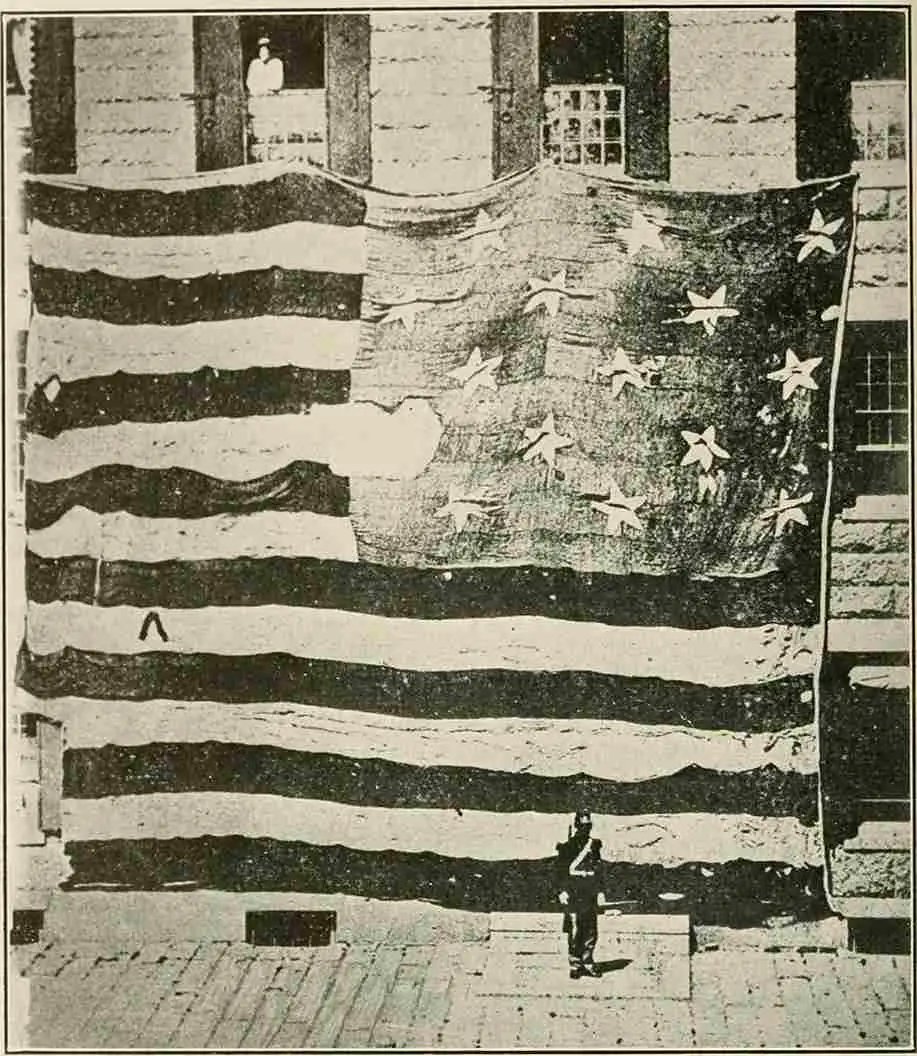

In 1873, Georgiana Armistead Appleton lent the flag to George Preble, a flag historian who thought it was lost. That year, Preble took the first known photograph of the flag at the Boston Navy Yard and displayed it at the New England Historic Genealogical Society until 1876.

While Preble had the flag, Appleton let him give away pieces as he wished. She also gave cuttings to other Armistead descendants and family friends. Appleton noted, “Had we given all that we have been importuned for, little would be left to show.” This tradition continued until 1880, when Armistead’s grandson gave away the last documented piece.

Some pieces of the flag have been found over the years. The National Museum of American History (NMAH) owns about a dozen, and curator Kathleen Kendrick said there are at least a dozen more in other museums and private collections.

However, the missing 15th star remains a mystery. “There’s a legend that the star was buried with one of the soldiers from Fort McHenry; another says that it was given to Abraham Lincoln,” Kendrick explained.

The flag’s conservation efforts

After Georgiana Appleton’s death in 1878, the flag went to her son, Eben Appleton. He lent it to Baltimore for its 1880 sesquicentennial celebration and later stored it in a New York City vault until 1907, when he lent it to the Smithsonian. In 1912, he made the donation permanent, ensuring the flag was publicly visible and well cared for.

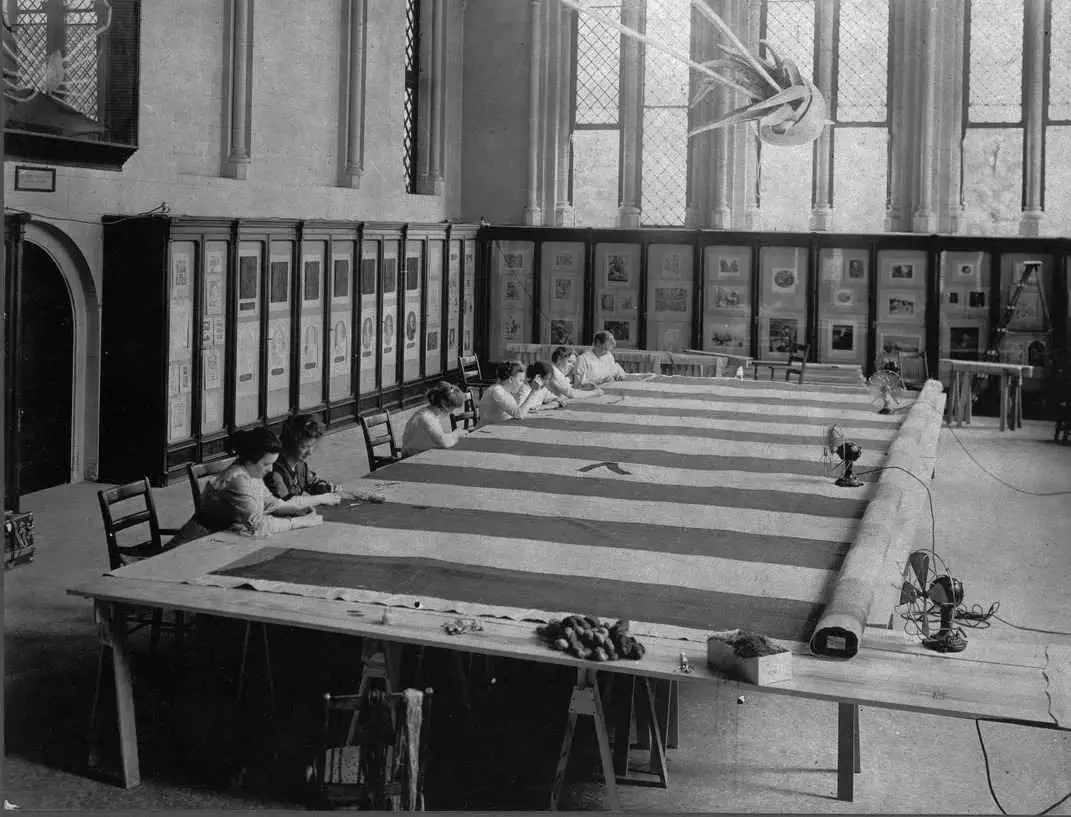

When the flag arrived at the Smithsonian, it was smaller and damaged from use and souvenir pieces being cut off. Amelia Fowler, an expert in flag preservation, restored it in 1914 with her patented linen backing method.

“Our goal was to extend [the flag’s] usable lifetime,” said Thomassen-Krauss. The aim wasn’t to restore the flag to its original appearance from Fort McHenry. “We didn’t want to change any of the history written on the artifact by stains and soil,” the conservator added. “Those marks tell the flag’s story.”

The flag was displayed at the Arts and Industries Building, though partially folded due to space constraints. In 1964, it became the centerpiece of the new National Museum of History and Technology, hanging fully for the first time.

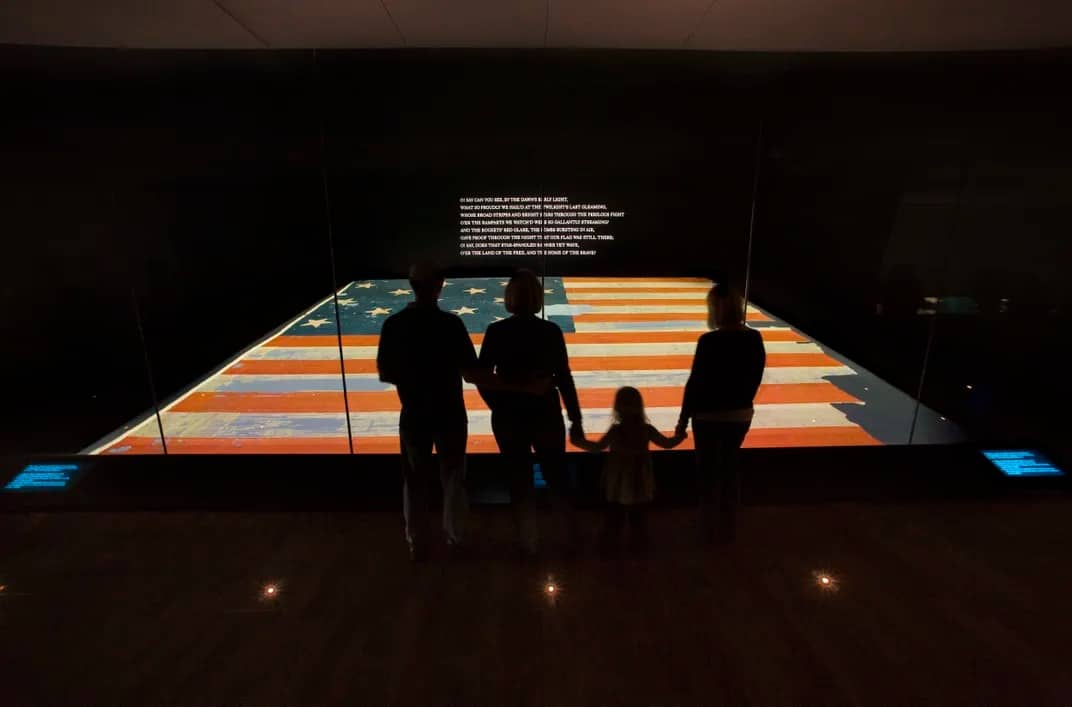

A major conservation project began in 1996, culminating in 2008 with the flag displayed in a climate-controlled gallery at the National Museum of American History.

“The survival of this flag for nearly 200 years is a visible testimony to the strength and perseverance of this nation, and we hope that it will inspire many more generations to come,” said Brent D. Glass, the museum’s then-director.

Transformation of Key’s poem into national anthem

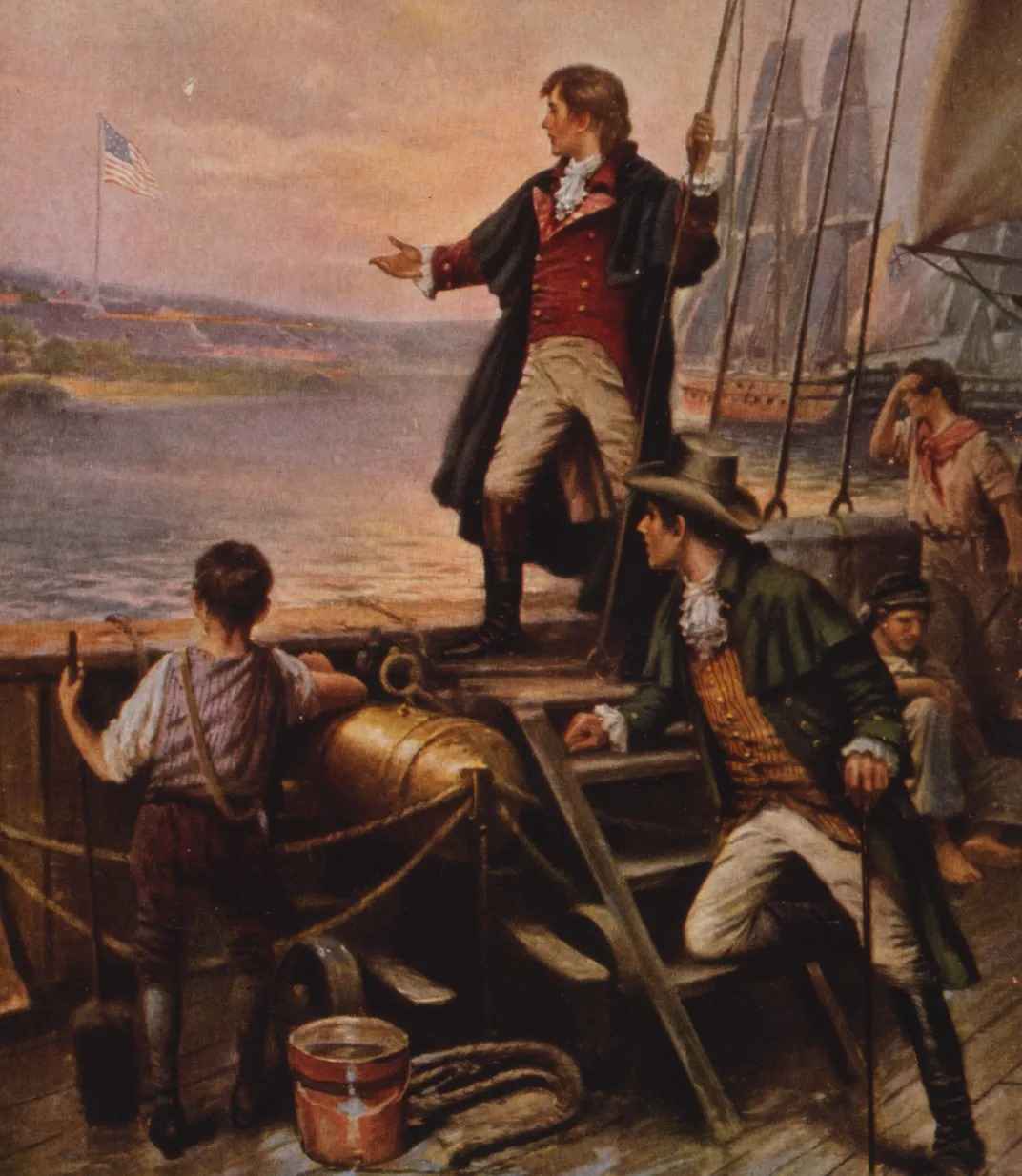

Francis Scott Key, a lawyer and amateur poet, found himself in an unexpected position during the War of 1812. In September 1814, Key boarded a British ship to negotiate the release of his friend, Dr. William Beanes, who had been captured by the British.

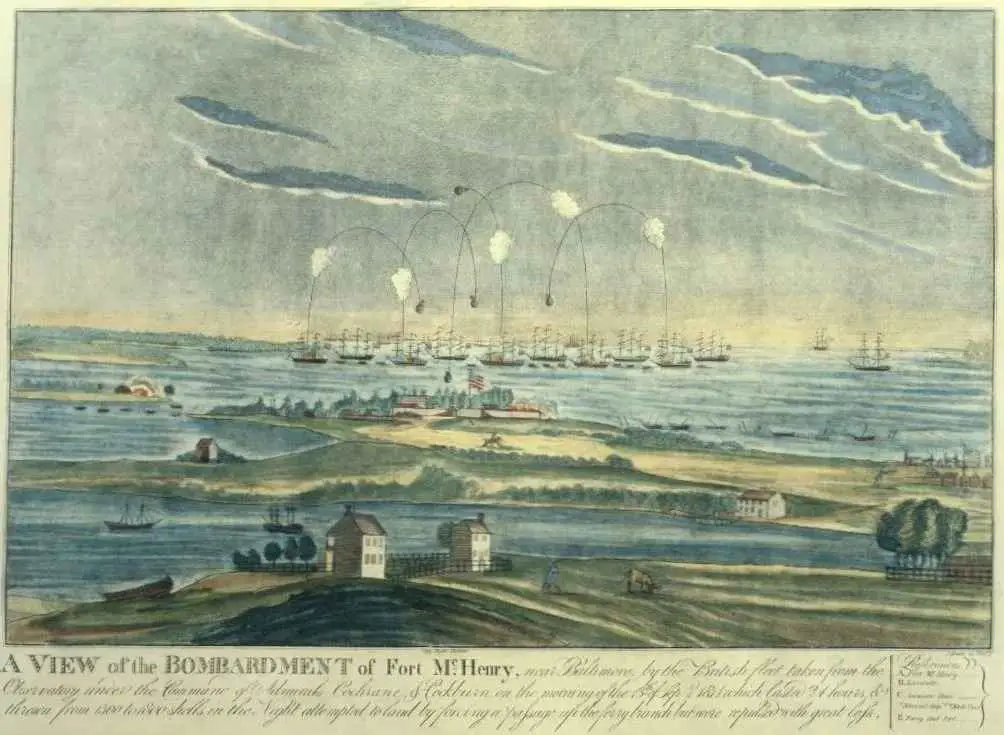

During these negotiations, Key witnessed the British bombardment of Fort McHenry in Baltimore Harbor. This intense 25-hour attack was part of the British campaign to capture Baltimore, a strategic American port.

From his point on the ship, Key anxiously observed the relentless assault. The night was filled with explosions, and the fort’s defense seemed uncertain.

“It seemed as though mother earth had opened and was vomiting shot and shell in a sheet of fire and brimstone,” Key later wrote. As darkness fell, he saw only red eruptions in the night sky. Given the scale of the attack, he was certain the British would win.

As dawn broke on September 14, 1814, Key was relieved to see the massive American flag still flying over Fort McHenry. This sight inspired Key to write a poem that captured his feelings of relief and patriotism.

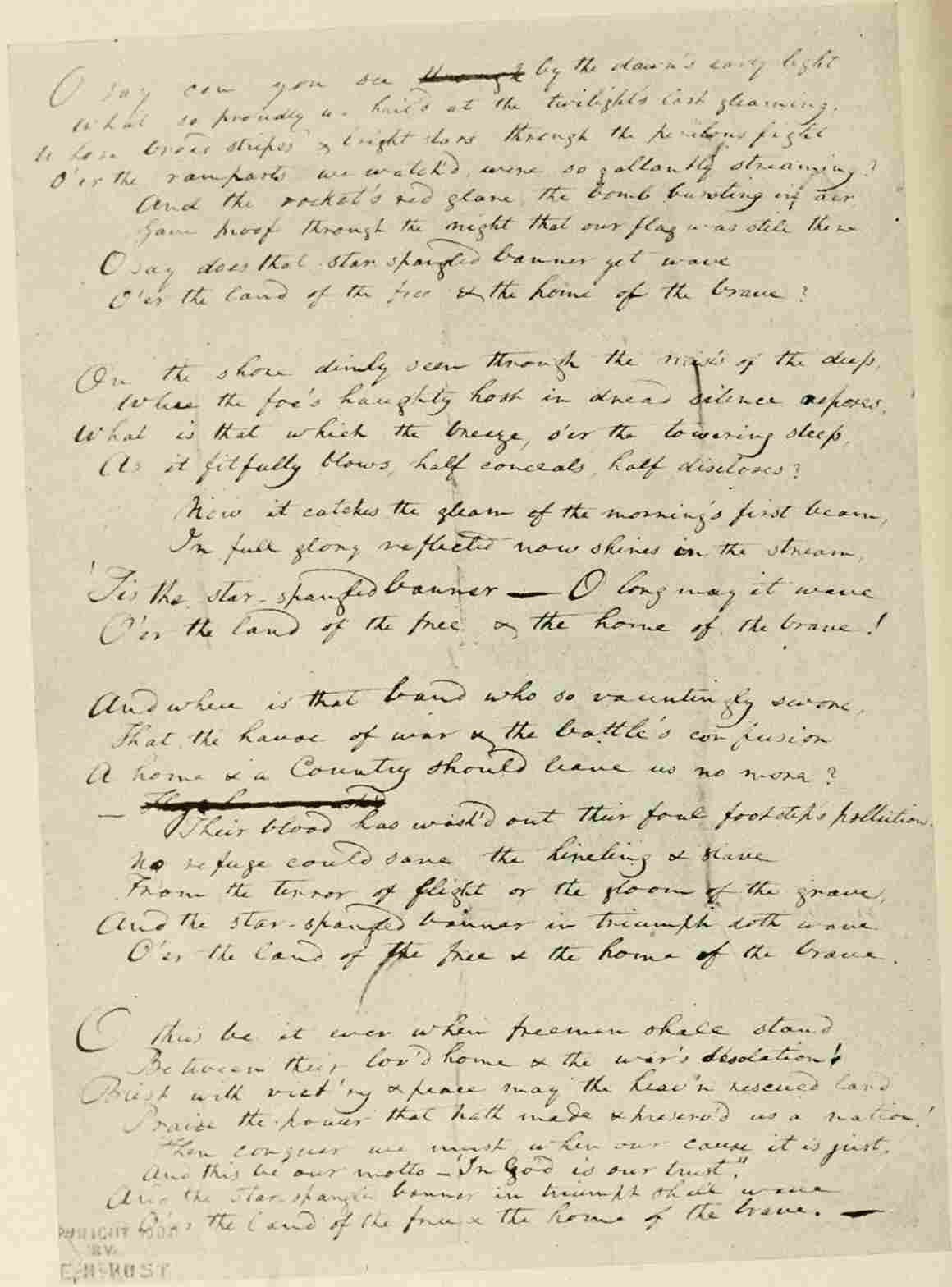

Key quickly jotted down verses on the back of a letter. His poem, originally titled “Defence of Fort M’Henry,” was later set to the tune of a popular British song, “To Anacreon in Heaven.” The melody, combined with Key’s stirring words, became widely popular and was eventually renamed “The Star-Spangled Banner.”

The poem’s vivid imagery and emotional resonance struck a chord with Americans. It was officially designated as the national anthem of the United States by Congress in 1931, forever linking Key’s words and the iconic flag with American identity and pride.

Symbolism and legacy of the flag

Reflecting on the Star-Spangled Banner’s significance, Kendrick said:

“The Star-Spangled Banner resonates with people in different ways, for different reasons. It’s exciting to realize that you’re looking at the very same flag that Francis Scott Key saw on that September morning in 1814. But the Star-Spangled Banner is more than an artifact—it’s also a national symbol. It evokes powerful emotions and ideas about what it means to be an American.”

The Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History in Washington, D.C., receives about four million visitors a year, according to military history curator Jennifer Jones, who is part of the team preserving the flag.

“It embodies our values, and everybody’s values are different,” she said. “People bring their own ideals to this object, not just this flag, but any American flag.”

After the War of 1812, the flag and the words it inspired became a sensation. “Those words were inspirational to a nation fighting to become independent and to create a more perfect union,” said Jones.

Today, the flag stands as an enduring symbol of democracy. “If you look at how fragile the flag is … that’s really synonymous with our democracy,” said Jones. “We have to be participants. We have to be thinking about it. We have to protect it.”