Wars could bring many surprises, and some laws passed during WWI, still in place in Britain today, are no exception.

When WWI began in 1914, Britain enacted new rules, with the most important being the Defence of the Realm Act (DORA) on August 8, 1914, to ensure public safety.

DORA gave the government the power to prosecute anyone whose actions were seen as a threat to military success or aiding the enemy. This broad definition meant DORA controlled nearly every aspect of life on the home front and expanded as the war continued.

Let’s explore the ten surprising measures introduced by DORA.

Whistling for a taxi

Whistling for London taxis was banned to prevent confusion with air raid warnings. Imagine a Londoner whistling for a cab late at night, only to be mistaken for signaling an air raid, causing unnecessary panic.

Britons were also prohibited from talking on the phone in a foreign language, buying binoculars, or hailing a cab at night. For example, if someone was caught speaking German on a phone call, they could be suspected of espionage and swiftly taken in for questioning.

These strict measures aimed to maintain security and order during a time of heightened tension.

Loitering

Under DORA, people’s movements were severely restricted. They could no longer go wherever they wanted, and activities such as hanging around areas near bridges and tunnels or lighting bonfires were banned. Some parts of the country even imposed curfews.

In 1915, Mona Jeffery, a respectable woman from Edinburgh, was arrested under DORA powers. Her crime? She had taken a photo of the Forth Bridge. As punishment, her camera was confiscated.

Criticism was aimed at DORA because it restricted people from participating in otherwise legal activities. Those who enjoyed kite flying or bell ringing, for example, did not believe their actions would actually impact Britain’s chances of winning the war.

These limitations were seen as unnecessary and overly restrictive.

Clocks go forward

One lasting impact of DORA is British Summer Time. Instituted in May 1916, this rule was designed to maximize daylight hours for work, especially in agriculture. By advancing the clocks an hour forward, people had more daylight in the evenings.

Under DORA’s powers, the government changed the time in spring and autumn to extend daylight working hours. This practice, still in effect today, standardizes time across the UK and continues to benefit various sectors.

Drinking

DORA imposed several rules that affected alcohol consumption. Pubs had to reduce their opening hours, and beer was watered down to make it weaker. Customers were also not allowed to buy rounds of drinks, thanks to the “No Treating Order,” which made it an offense to purchase drinks for others.

These measures were introduced because claims arose that drunkenness was hampering war production. As a result, licensing laws were also introduced, restricting pub opening times to lunchtime and evening hours, closing at 11 pm.

By controlling the strength of beer, the government aimed to reduce intoxication and maintain productivity among workers.

Some people feared that DORA was limiting their free time. They were angry about having to drink weaker beer, not being allowed to go to the pub whenever they wanted, and not being able to buy their friends a drink. These restrictions caused frustration and resentment among the public.

Drugs

For the first time, drugs were banned under DORA. Cocaine and opium possession became illegal except for medical professionals. These drugs, desperately needed in hospitals, could no longer be used recreationally as they had been previously.

Unauthorized possession of cocaine or opium became a criminal offense, reflecting the government’s effort to prioritize medical use and curb recreational abuse.

Compulsory blackouts

A blackout was introduced in certain towns and cities to protect against air raids. British towns and cities had to go dark, hiding them from enemy aircraft and reducing the risk of bombings.

Plans for blacking out British coastal towns in wartime were drawn up in 1913 by Winston Churchill, then First Lord of the Admiralty. These plans were implemented on August 12, 1914, just eight days after the UK entered the war.

On October 1, 1914, the Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police ordered that bright exterior lights in London be extinguished or dimmed and street lamps partially painted with black paint. In other areas, local authorities decided on blackout measures.

When the German bombing campaign began in early 1915, some towns without blackouts saw residents taking matters into their own hands, smashing street lamps to prevent attracting air raids. By February 1916, blackout restrictions were extended to the whole of England.

Press censorship

Censorship was a key part of DORA, regulating what the press could and couldn’t report. Press censorship severely limited the reporting of war news, and many publications were banned.

DORA also banned public discussions and rumors about military issues. Newspapers faced strict censorship regarding their war coverage.

The first person arrested under DORA powers was John Maclean, a Glasgow school teacher. Active in anti-war campaigns, Maclean was arrested for his outspoken anti-war speeches.

Censoring newspapers and stopping rumors about military matters also caused concerns. People were unsure if they were getting the truth and didn’t know how Britain was faring in the war or if it faced defeat. This uncertainty created a sense of mistrust and confusion among the public.

Postal censorship

Censorship under DORA extended to private letters, particularly between soldiers and their families or anyone writing abroad. Military censors examined 300,000 private telegrams in 1916 alone.

Anyone sending a letter abroad was forbidden from using invisible ink. Military censors read soldiers’ letters to ensure no secrets were being disclosed, affecting personal communication.

Soldiers writing home knew their letters would be read, often limiting what they felt comfortable sharing.

White flour production

DORA imposed strict rules to preserve food stocks. Bread, a staple during the war years, was heavily regulated. It became illegal to use spare food, like bread, to feed chickens, ducks, and horses.

Fines were imposed for producing white flour instead of whole wheat and for poor rat control in wheat stores. These restrictions on food production eventually led to the introduction of rationing in 1918.

Foreign nationals

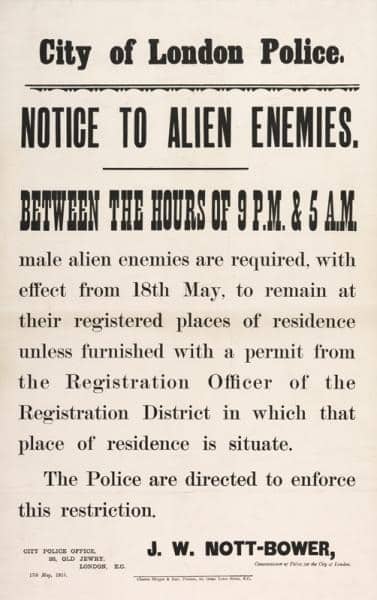

DORA placed heavy restrictions on foreign nationals from enemy countries living in Britain. Their freedom was severely limited, with many interned. These “aliens” had to register their residence and were restricted in their movements, often limited to certain times of the day.

Opponents of the war could also be arrested and imprisoned. Foreign spies caught in Britain faced harsh punishments under DORA. For instance, Carl Lody, a German, was caught sending letters from Edinburgh to Berlin that could aid the enemy. He was executed in November 1914.