The rapid growth of New York City starting in 1820 set the stage for gang culture to flourish. The city was flooded with poor immigrants from various backgrounds who sought community in the chaotic urban landscape.

Factors like overcrowding, poverty, and a strong sense of identity bonded these diverse groups. In such tumultuous times, some individuals quickly recognized opportunities to profit from the chaos.

One notorious figure from this era was Fredericka Mandelbaum, known as “Old Mother,” “Marm,” or the “Queen of Fences.” She became the talk of the town, with everyone from police officers to writers discussing her. Her death even made international headlines in February 1894.

Her early life

Marm was born Friederike Henriette Auguste Wiesener in 1827 in Hanover, Prussia. At 23, she joined her husband, Wolf Israel Mandelbaum, in New York City after he immigrated there.

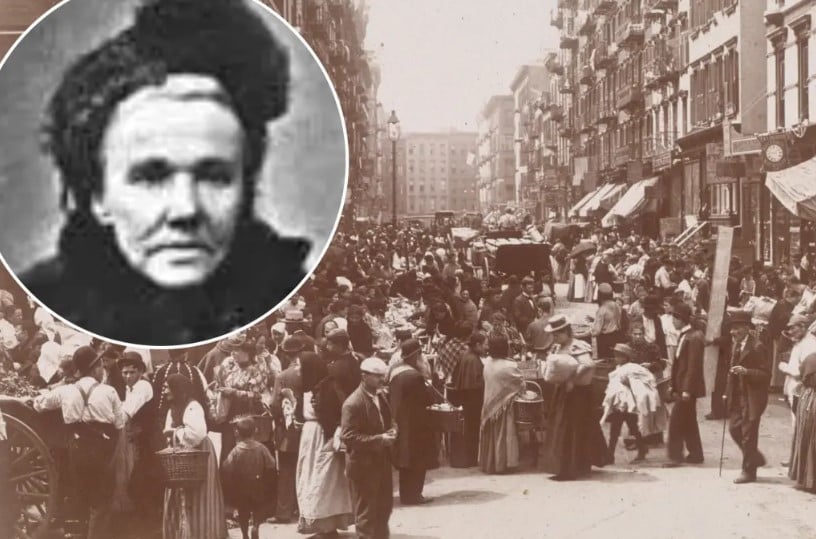

They settled in the Lower East Side, an area called Kleindeutchland (Little Germany), where 15 people crammed into small tenement apartments of just 325 square feet. The air in these cramped spaces was hardly enough for one person.

Children were cautioned to stay away from the mysterious Gypsy women on Orchard Street, known for their flowing skirts and flashy gold jewelry. However, most families in Little Germany didn’t have fortunes worth chasing after.

After the economic collapse in 1857, life became even harder for struggling families. With businesses shutting down, banks failing, and countless people out of work, hungry children wandered the streets, selling scraps of rope and coal to get by. Many turned to stealing from vendors and pickpocketing, often with their parents’ approval.

“I was not quite 6 years old when I stole my first pocketbook,” wrote Sophie Lyons, who would later become one of Marm’s most successful protégés. “I was very happy because I was petted and rewarded; my wretched stepmother patted my curly head, gave me a bag of candy, and said I was a ‘good girl.’ ”

How she lived as a queen

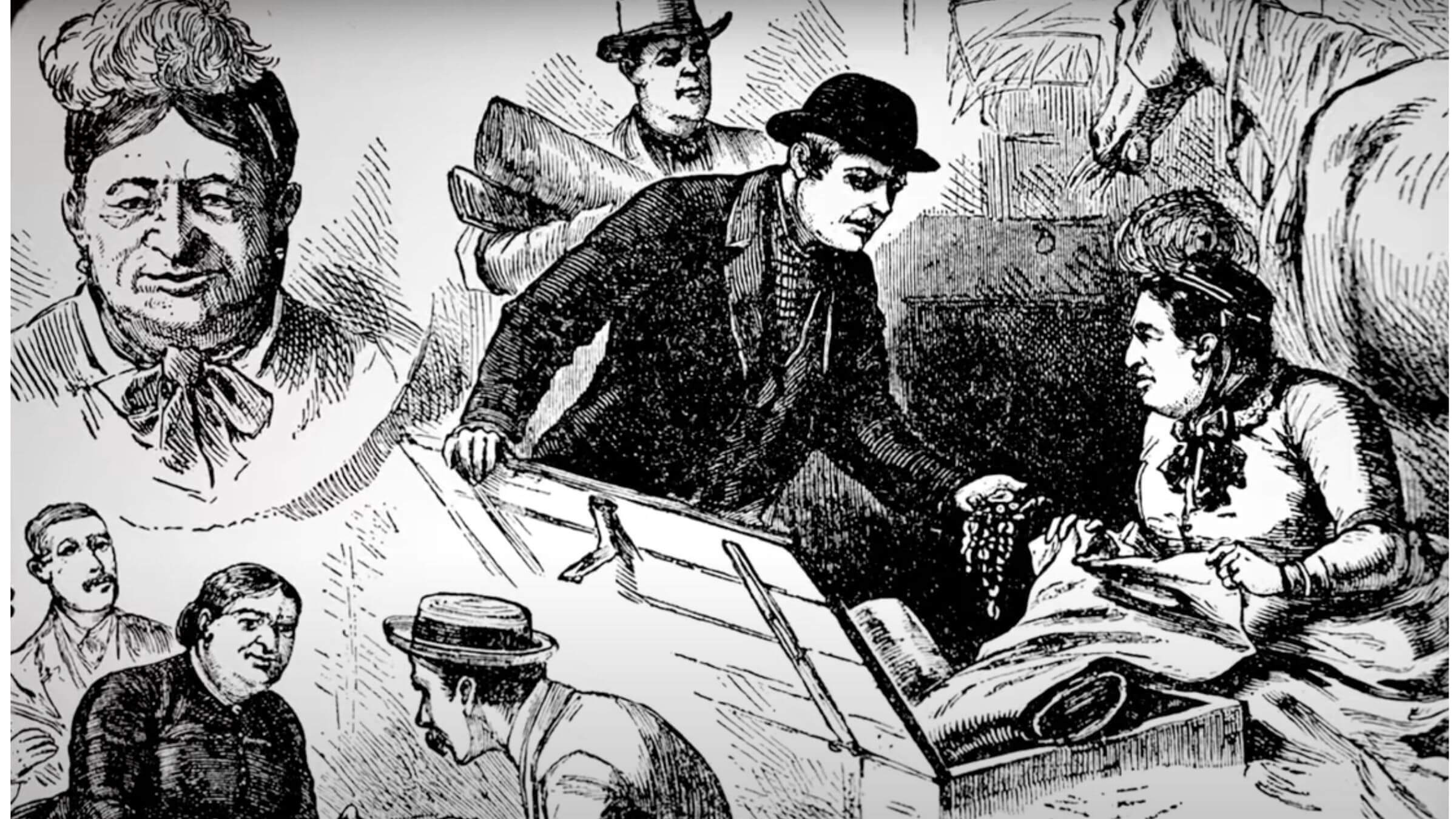

Marm Mandelbaum was truly the central figure in a vast underground network on Manhattan’s Lower East Side. Marm had the eyes of a sparrow, the neck of a bear and fat, florid cheeks. Her hair, styled in tight black rolls and adorned with a feathered fascinator, added a touch of humor to her otherwise tough appearance. Known for her sparse but impactful speech, she cherished her own mantra, “It takes brains to be a real lady,” and lived by it.

She was regarded as a motherly figure among a unique “family” of confident men, pickpockets, shoplifters, and burglars. Marm wasn’t just a passive overseer—she actively helped these street urchins and sneak thieves sharpen their pickpocketing and petty crime skills, turning them into skilled operators in New York’s hidden world of crime.

For over 20 years, Mother Mandelbaum was the go-to for receiving and laundering stolen goods, operating right out of her unassuming shop on Clinton Street in New York’s Lower East Side. To the public, she sold dry goods and haberdashery, but behind the scenes, she was the queen of crime. Her influence and wealth allowed her to hire top lawyers and keep the police on her side.

Reasons for Her Loyalty Among Many

Marm Mandelbaum, a sharp-minded entrepreneur, built a profitable underworld network through trust, loyalty, and strategic manipulation. Her store was a bustling hub for female gangsters, where she played multiple roles—mentor, banker, agent, and even a host for elaborate gatherings.

She offered her “associates” financial support, handled their stolen goods, and even put in requests for items to be pilfered, making her operation a one-stop shop for New York’s infamous underbelly.

When her partners got caught, she didn’t hesitate to bail them out, but always at a hefty cost—ensuring they were both indebted and loyal to her.

What people said about her

In 1884, the co-director of the Pinkerton National Detective Agency, Robert Pinkerton, said of Mandelbaum, “She is known at least by name to every thief and detective in the United States, and has received plunder from nearly every city in the country secured by traveling gangs of professional thieves.”

The city’s Chief of Police, George W. Walling, wrote in his memoir, “She attained a reputation as a business woman whose honesty in criminal matters was absolute,” while her obituary in The New York Times noted, “her success was in a great measure due to her friendship for and her loyalty to the thieves with whom she did business. She never betrayed her clients, and when they got into trouble she procured bail for them and befriended them to the extent of her power.” And the Brooklyn Daily Eagle called her (perhaps with a tinge of irony) “a most respectable and philanthropic receiver of stolen goods in New York.”

In spring 1884, New York District Attorney Peter Olson brought in the Pinkerton Detective Agency to break up Marm Mandelbaum’s criminal network. Pinkerton detective Gustave Frank, posing as “Stein,” learned the trade from a silk merchant to gain Marm’s trust. After being introduced by a “trusted” client, Marm began doing business with him. Soon after, police raided her warehouses and found the silk Frank had sold her along with enough stolen goods to convict her for life.

Even as she failed to appear at her final court date, the prosecuting attorney admitted, “I suspected it…the old girl…was so awfully cocky. She had been in the business so long that she positively thought it was improper for us to arrest her.”

And her lawyers, attributing her flight to “impulsive mania” did not “regard the unfortunate victim…with any degree of sorrow, for they laughed merrily and winked sympathetically.”

Mother Mandelbaum’s story, as reported by Walling and Lyons, offers a peek into the criminal world of late 19th-century New York City. Her protégé, Sophie Lyons, claimed that the tale of the “uncrowned ‘Queen of the Thieves’” emphasized the idea that “CRIME DOES NOT PAY.” Despite this warning, Mandelbaum is portrayed as a folk anti-hero, earning the reluctant respect of her enemies.