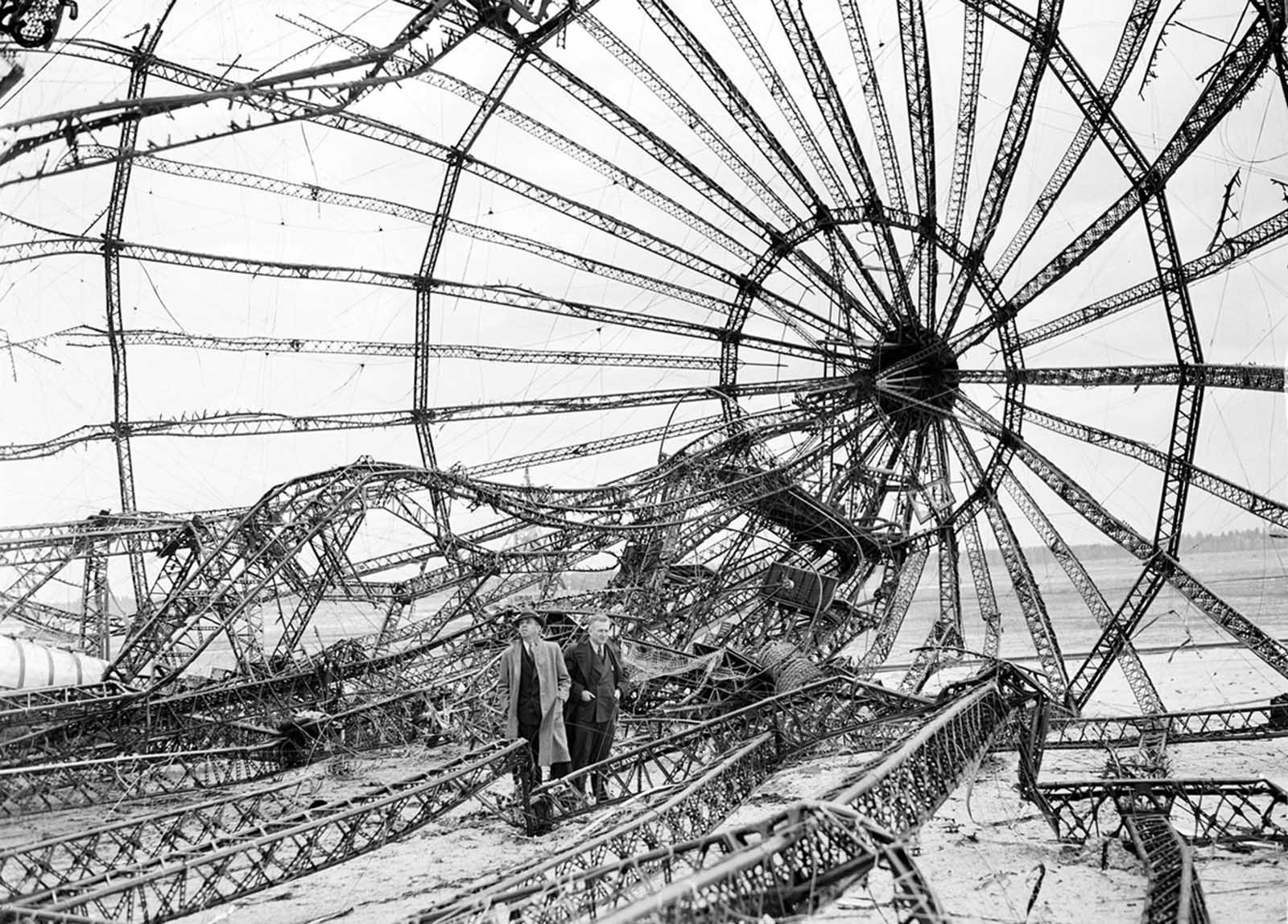

When the massive German dirigible Hindenburg caught fire over Lakehurst, it resulted in the deaths of 36 people and left behind a wreckage of burning debris. The disaster quickly turned into a compelling mystery: What caused this horrific event?

Right from the start, theories began to surface. Just a few days after the incident, the New York Daily News was already speculating on various causes.

Some suggested natural events like lightning, while others pointed to more alarming possibilities like sabotage. Each theory added to the confusion and mystery surrounding the event.

The speculation didn’t stop there. In the following weeks, experts, enthusiasts, and even some with wild ideas flooded the investigation with their own theories.

The Hindenburg was Nazi Germany’s pride and joy

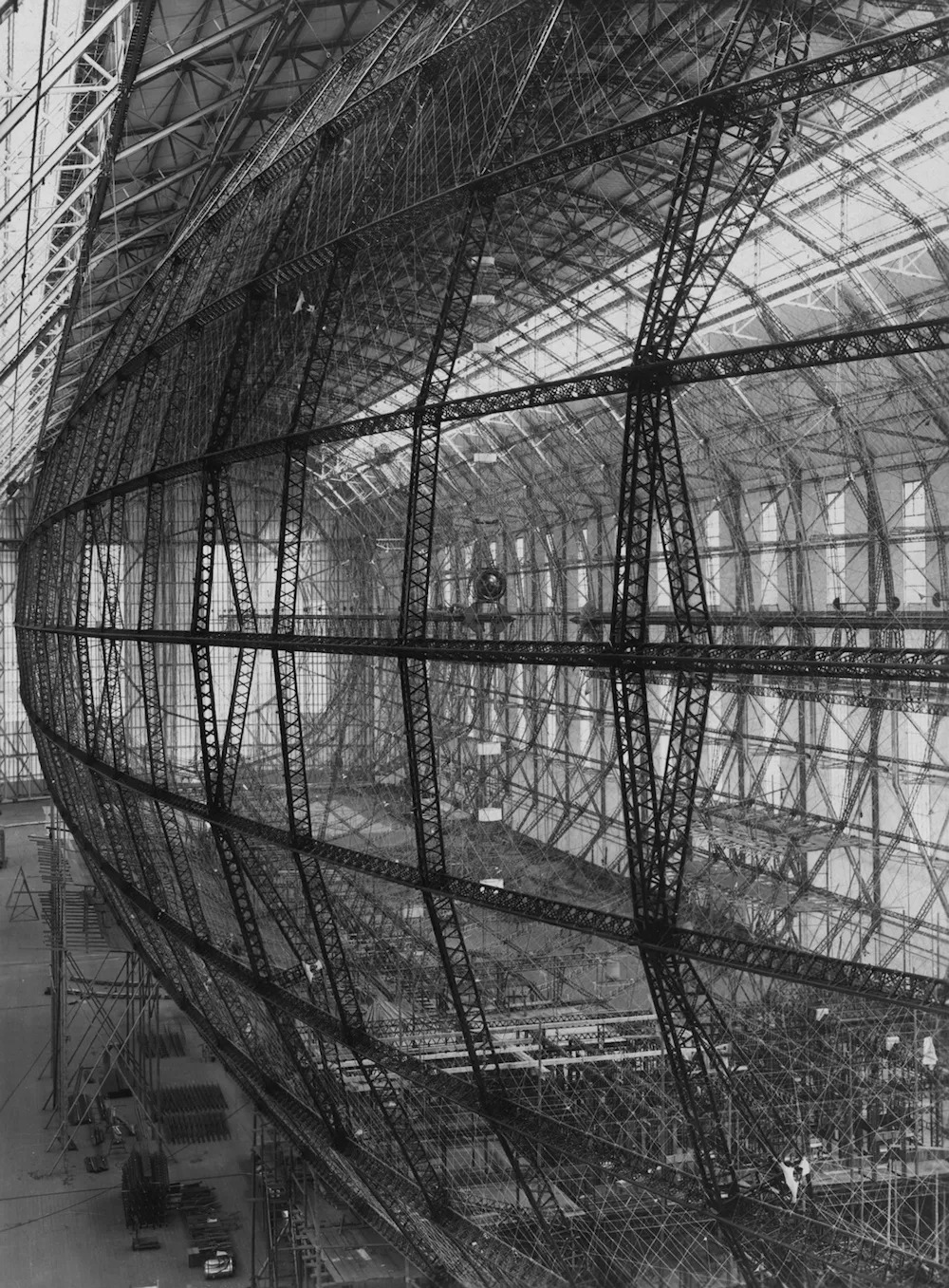

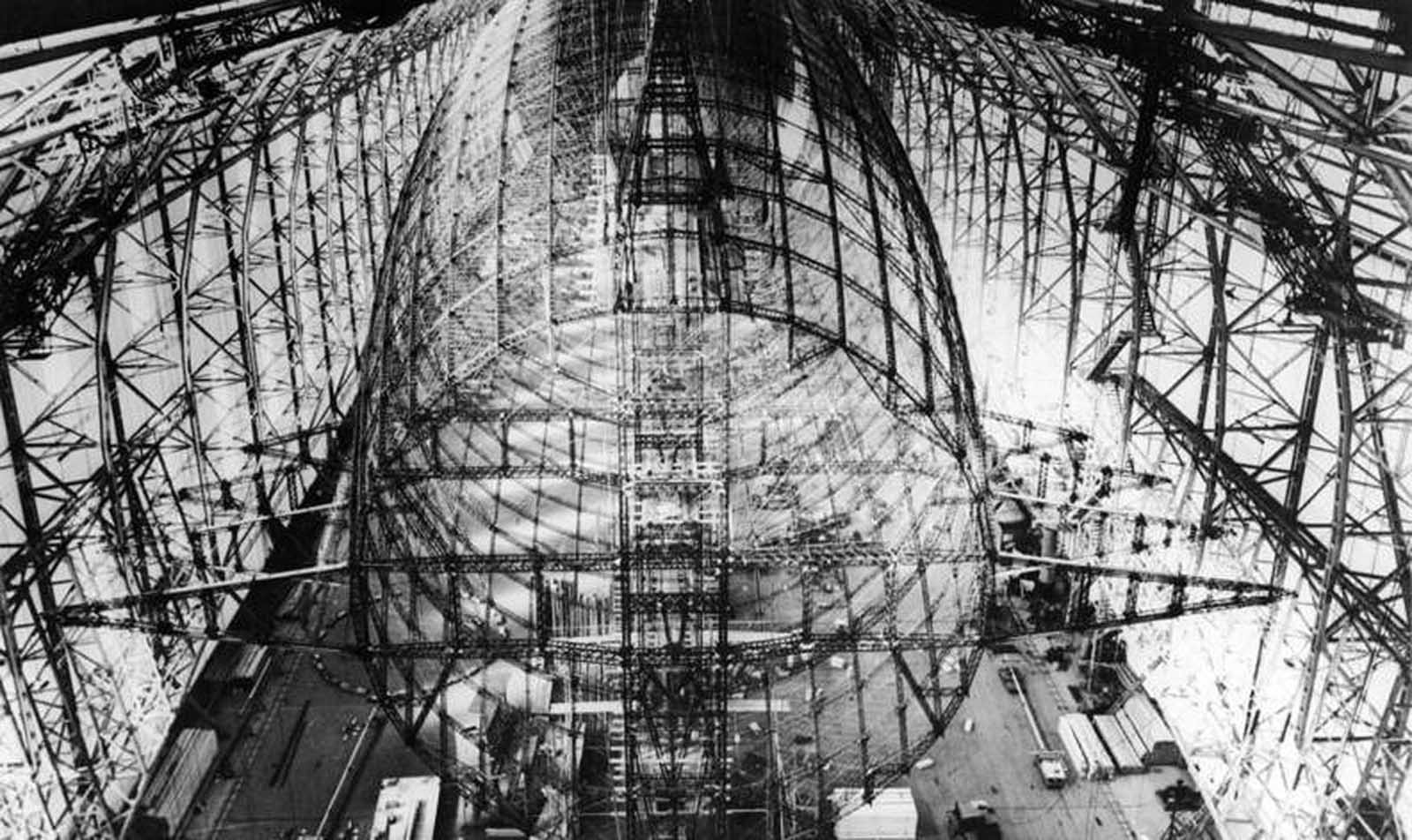

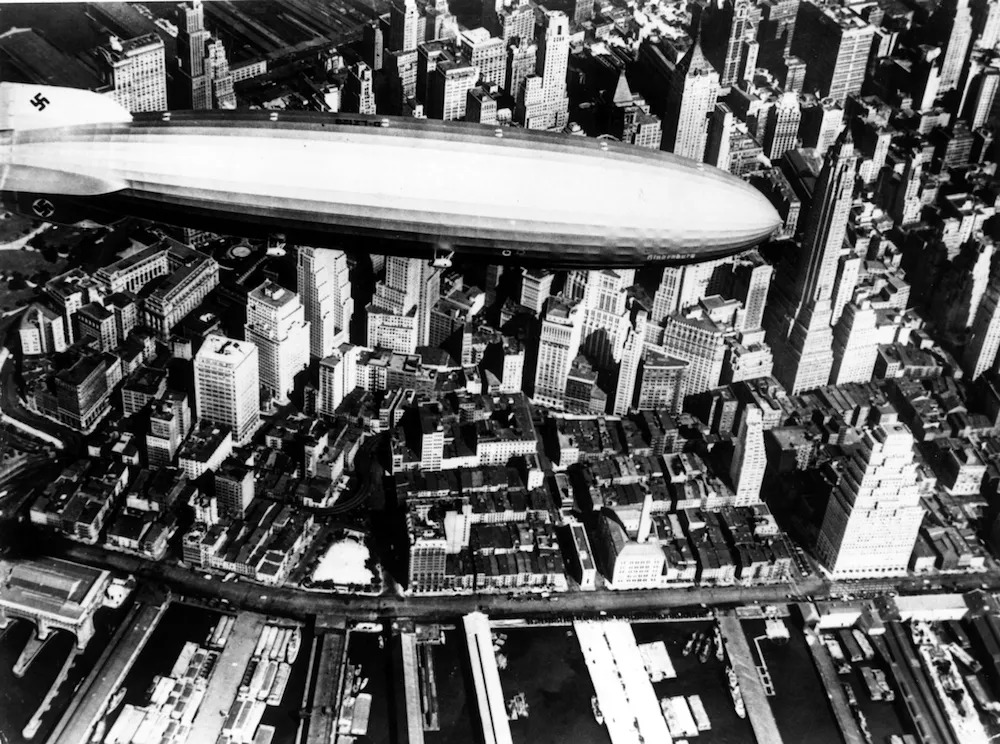

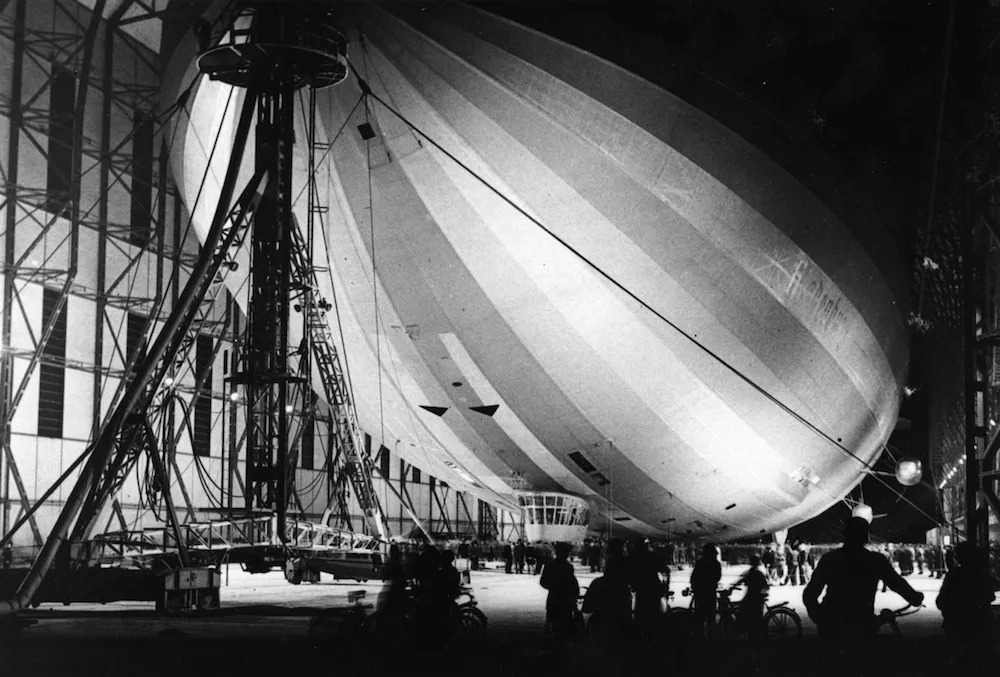

In 1936, the future seemed promising for rigid airships, also known as dirigibles or zeppelins. The Hindenburg, a symbol of Nazi Germany’s technological pride, made headlines as it carried passengers across the Atlantic in style.

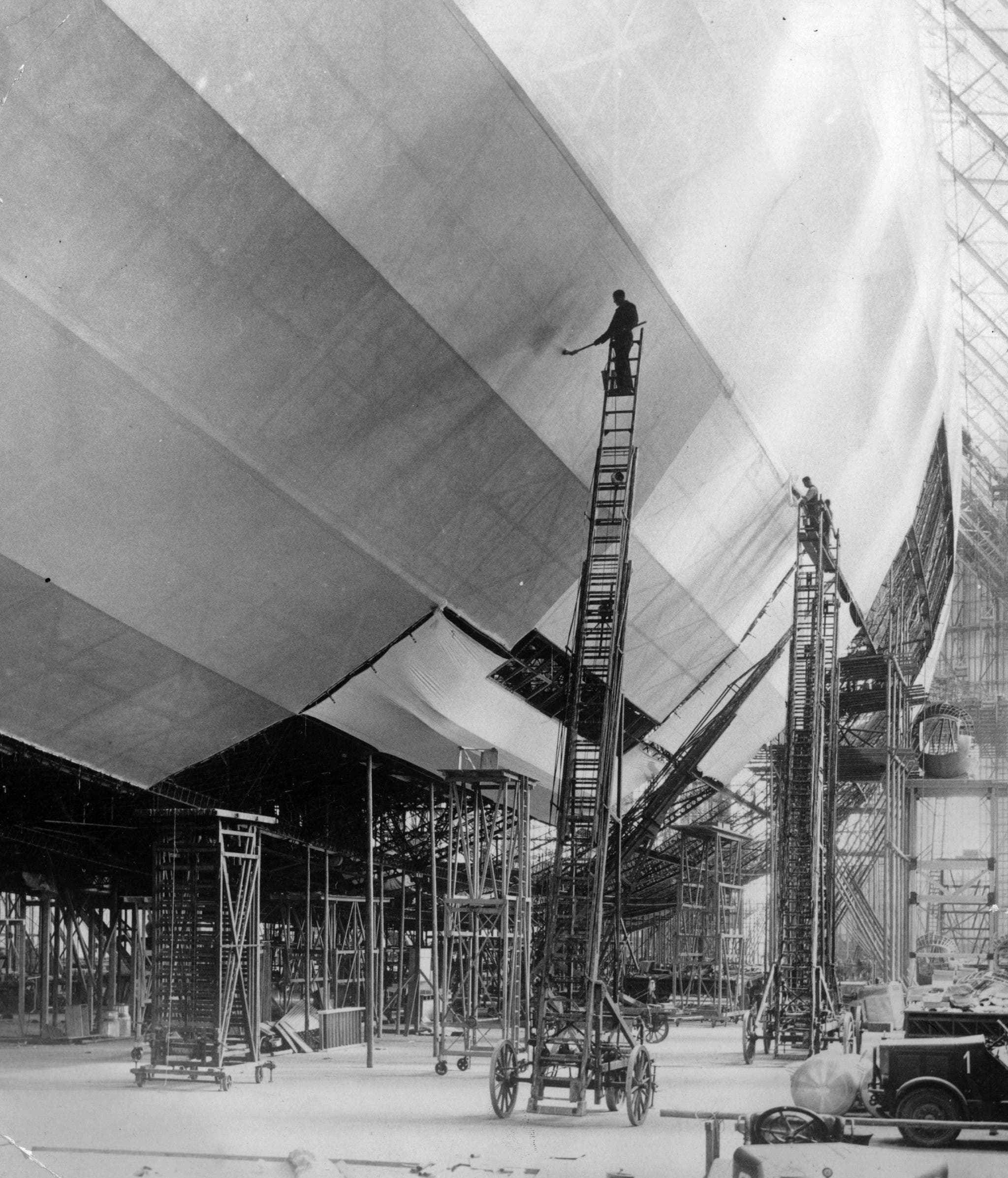

The Hindenburg, a massive 245 meters (804 feet) long, was launched from Friedrichshafen, Germany, in March 1936.

With a maximum speed of 135 km/h (84 mph) and a cruising speed of 126 km/h (78 mph), it quickly became known for its luxurious transatlantic flights, completing 10 round trips between Germany and the United States with 1,002 passengers.

Interestingly, the Hindenburg was initially designed to use helium gas, which is safer and non-flammable. However, due to U.S. export restrictions against Nazi Germany, the airship was filled with hydrogen, a highly flammable gas, instead.

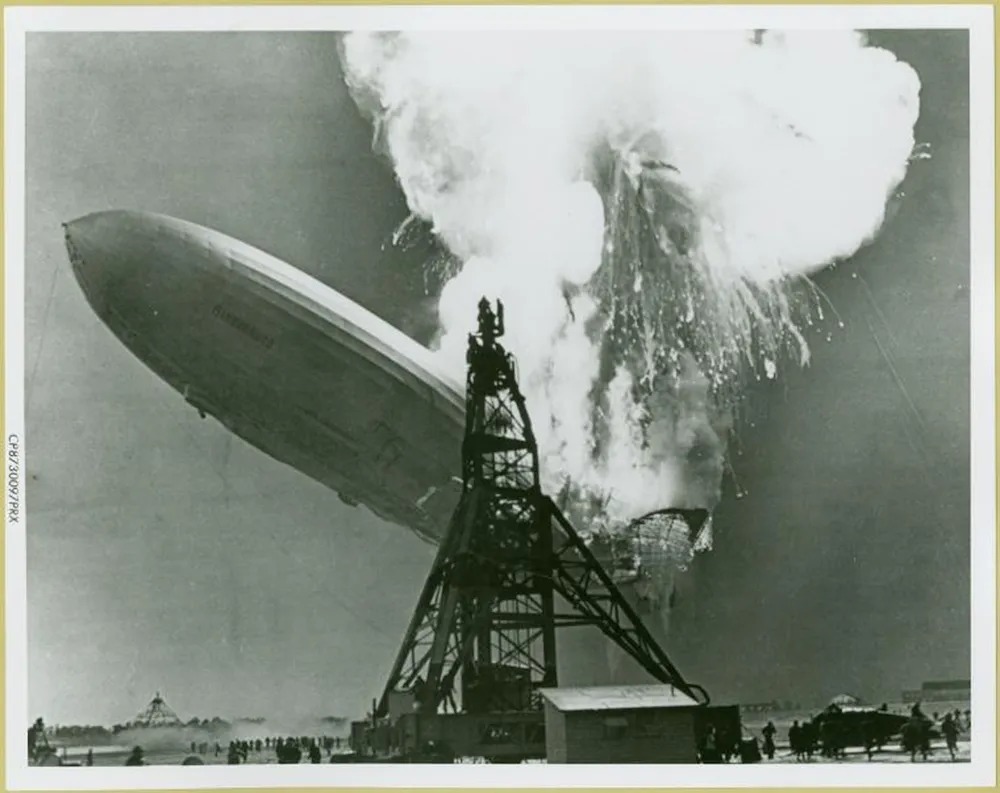

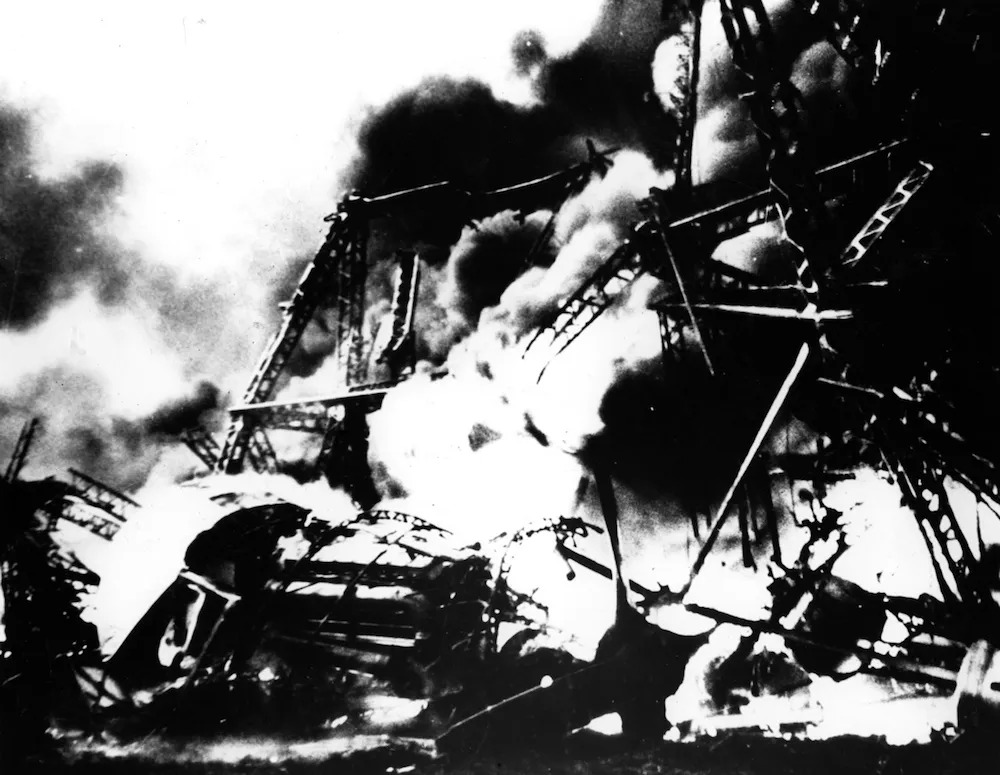

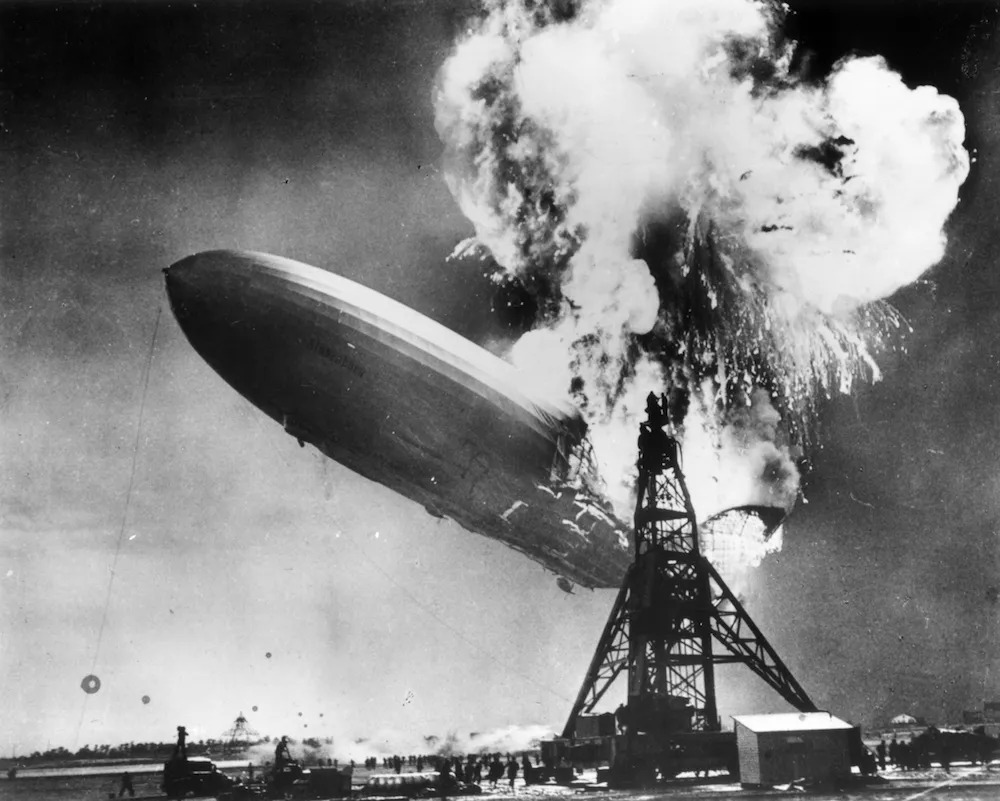

The 30-second crash shocked the world

On May 6, 1937, the Hindenburg airship was nearing the end of its 35th transatlantic journey, having left Frankfurt, Germany, and almost reached Lakehurst, New Jersey.

Out of the blue, after a trouble-free voyage, the majestic zeppelin suddenly burst into flames just under 300 feet from the ground.

Under a minute, the massive ship was reduced to ash and wreckage as it crashed down, killing 36 people. Passengers and crew were seen desperately trying to escape.

The world watched in shock as unforgettable images of the flaming zeppelin and its tragic descent were broadcast.

That night, newspapers around the world splashed the dramatic photos on their front pages while newsreel footage was shown in theaters the next morning.

Radio announcer Herbert Morrison’s emotional broadcast on May 6, 1937, as he witnessed the Hindenburg disaster, became legendary.

His anguished cry, “Oh, the humanity!” was broadcast live and quickly became one of the most memorable audio recordings of the event.

The Nazis rejected the sabotage theory

When news of the Hindenburg disaster reached German Chancellor Adolf Hitler at his mountaintop retreat in Berchtesgaden, his reaction was one of “stunned silence.” The catastrophe struck a heavy blow, and the initial shock left him at a loss for words.

Hugo Eckener, a prominent figure in German airship development and head of the Hindenburg’s manufacturing company, initially considered the possibility of sabotage.

However, he quickly changed his stance, suggesting that a stray spark might have ignited the airship’s highly flammable hydrogen gas.

Nazi leader Hermann Göring, head of the German air command, was swift to dismiss the sabotage theory.

He attributed the disaster to an “act of God,” proclaiming, “We bow to God’s will,” and vowed to continue advancing the regime’s goals with relentless determination. His dismissal of sabotage seemed puzzling.

In his 2021 book, “Empires of the Sky,” author Alexander Rose speculates on why the Nazis were so quick to reject the sabotage theory.

He suggests that if sabotage had been the cause, it would have shown that Hitler was not universally liked and would have hurt the image of Germany as a stable and orderly nation under Nazi rule.

This could have given enemies of the Reich, like Jews and Communists, false hope that the regime was vulnerable.

Conspiracy theories emerge

Unlike their German counterparts, Americans had no restrictions on their investigation into the Hindenburg disaster.

Contemporary newspaper reports and declassified FBI files reveal that, even though the FBI didn’t conduct a formal investigation, it helped the U.S. Commerce Department’s inquiry and gathered theories from the public.

Many American correspondents leaned towards sabotage rather than technical faults.

The theories ranged from anti-Nazi groups—like communists, Jews, or Spaniards opposed to Germany’s support for Francisco Franco—to more far-fetched ideas suggesting the Nazis themselves had orchestrated the explosion to claim insurance money.

Various imaginative scenarios emerged. Some believed an incendiary bullet fired from the ground caused the fire. Others suggested a small plane might have attacked the Hindenburg from above.

One theory even proposed that a New York City police lieutenant, acting on orders from Mayor Fiorello La Guardia, shot down the dirigible. The most common theory was that a bomb hidden inside the airship was detonated by a timer or barometric changes.

One theory focused on Joseph Spaeh, an American passenger with a background as a contortionist and acrobat.

Spaeh’s aloof demeanor and his ability to maneuver within the airship’s structure made him a suspect in the eyes of some. Despite these suspicions, the FBI’s investigation found no evidence linking Spaeh to the disaster.

Spaeh was not the only suspect in the Hindenburg disaster. In a well-known 1962 book, “Who Destroyed the Hindenburg?”, writer and military historian A. A. Hoehling suggested that Eric Spehl, a 26-year-old rigger, might have been the saboteur.

Hoehling’s theory proposed that Spehl, allegedly influenced by his communist girlfriend, planted a bomb on the airship. However, Hoehling admitted that his case was based on circumstantial evidence.

The suspicion surrounding Spehl continued into the 1970s. In 1972, Michael M. Mooney’s book, “The Hindenburg,” also pointed to Spehl as the person behind the disaster.

This led to a German investigation, where Spehl’s ex-fiancée rejected the idea, calling it “absolute madness.”

Despite this, Mooney’s book inspired the 1975 film The Hindenburg, which told a similar story but used a different name for the alleged saboteur.

The real Eric Spehl, however, could not defend himself. He had tragically died in the Hindenburg crash in 1937, leaving behind no chance to clear his name.

Official story: Was it just bad weather that caused the Hindenburg to burn?

The U.S. and German governments each conducted their own investigations into the Hindenburg disaster, releasing their reports in July 1937 and January 1938, respectively.

Both reports attributed the tragedy to atmospheric conditions on that rainy night but differed on the specifics.

The American investigation suggested that a “brush discharge” could have ignited leaking hydrogen, causing the fire. In contrast, the German report supported Hugo Eckener’s spark theory.

Despite these conclusions, neither investigation completely ruled out sabotage, and conspiracy theories have continued over the years.

Today, most experts agree that the disaster was likely an accident, but the exact cause or potential involvement of sabotage may never be known for sure.