Betty Skelton was a trailblazing figure in the world of aviation and motorsports. Known for her fearless spirit and exceptional skills, she made a name for herself as a pilot, aerobatics performer and then race car driver.

Bill France stated, “I would venture to say there is no other woman in the world with all the attributes of this woman. The most impressive of them all is her surprising and outstanding ever-present femininity, even when tackling a man’s job”.

Betty Skelton’s Journey Into The Skies

Betty Skelton was born in Pensacola, Florida, on June 28, 1926. Her parents were young when they had her, and she was their only child.

Even as a little kid, she was obsessed with airplanes, especially the ones flying over her house near the Naval Air Station. Instead of playing with dolls, she loved playing with model airplanes.

When she was 8, she began reading books on aviation and that made her parents realize how serious she was about flying.

Whenever they could, her family would hang out at the local airport, and Betty would charm pilots into letting her go for rides on their planes.

Kenneth Wright, a Navy ensign, took a special interest in the Skeltons and decided to become her instructor. He let her fly his Taylorcraft airplane solo at just 12 years old, even though it wasn’t allowed. When Betty turned 16, she got her private pilot’s license from the Civil Aviation Authority.

She wanted to join the Women Airforce Service Pilots (WASP) program, but you had to be 18½, so she had to wait.

This program let women fly Air Force pilots and planes to their destinations, and it was the only one that took women. Unfortunately, it ended four months before Betty turned 18½.

At age 18, Betty got a job as a clerk for an airline but kept on flying. She also got her commercial pilot’s license and became a flight instructor the next year. She started teaching at Tampa’s Peter O. Knight Airport. A few years after the Civil Air Patrol began in 1941, Betty joined them too.

Breaking Barriers In Aviation And Setting New Heights

Skelton’s dad, David, held an amateur airshow in 1945 to raise money for the local Jaycees. When the airport manager in Tampa suggested Bettydo some basic stunts, she accepted the challenge though she’d never done aerobatics before.

She borrowed a Fairchild PT-19 and was taught by Clem Whitteneck, a famous aerobatic pilot from the 1930s. Within two weeks, she got the hang of it and mastered simple tricks at the air show, which she would perform on the show.

In 1946, she bought her own biplane, 1929 Great Lakes 2T-1A Sport Trainer biplane, and performed at the Southeastern Air Exposition, kicking off her pro aerobatic career.

Skelton could do lots of tricks, but her most impressive maneuver involved flying upside down and cutting a ribbon with her propeller just 10 feet off the ground.

With that experience came a career. She made a career change and became an aerobatic pilot. Shortly after, she got her own plane, which she named Little Stinker, and flew all kinds of aircraft like blimps, gliders, helicopters, and jets.

“My first aerobatic biplane, at Great Lakes, was a real crate! I found it behind a hangar. It was in bad shape. It had crashed and was in pieces. It was not nearly as manageable as a true aerobatic plane should be,” she said.

In 1949, she set a world record by flying a Piper Cub to a staggering altitude of 25,763 feet (7,853 meters).

Just two years later, she broke her own record, reaching an incredible height of 29,050 feet (8,850 meters), still in a Piper Cub.

Not stopping there, she also claimed the world speed record for piston-engined aircraft by flying a P-51 Mustang racing plane at an astonishing 421.6 mph (678.5 km/h) over a 3-kilometer course. I

n 1950, she took on a new role as the hostess of Van Wilson’s Greeting Time, a popular radio show.

The incredible woman claimed, “It is not easy to be the best. You must have the courage to bear pain, disappointment, and heartbreak. You must learn how to face danger and understand fear, yet not be afraid. You must establish your goal, and…in your every waking moment you must say to yourself, ‘I can do it.’”

But while records she set, along the way, friends she lost. In her words,

“One of the hard things about flying the aerobatic circuit was enduring the pain of watching friends die. At times it felt like a waiting game. I wondered who would be next. Learning to fear death without actually being afraid was something you had to do to make it through.”

Despite her remarkable achievements, she began to feel frustrated with the lack of new challenges in aerobatics.

The demanding air-show circuit left her mentally and physically drained, prompting her decision to retire from aerobatics.

How Betty Skelton Became Speed Queen

Skelton found a new interest in cars. In 1954, she got invited to be a pace car driver for a race during Nascar’s speed week in Daytona Beach, Florida, by Bill France Sr., one of the founders of the stock-car circuit.

They met when she flew some of his drivers to Pennsylvania. Back then, Nascar didn’t have the famous racetrack in Florida, so she drove on the beach, speeding around tide pools.

After parking the pace car, she hopped into a Dodge sedan and set the women’s stock-car speed record at 105.88 mph. Two years later, she boosted the speed to 156.99 mph.

Her love for racing took her across South America’s Andes Mountains and Mexico’s Baja Peninsula. This passion also extended to her work in advertising, where her keen sense of style shone.

In the mid-1950s, when female ad executives were rare, she excelled, particularly in promoting Chevrolet.

Her Dream To Fly In The Space

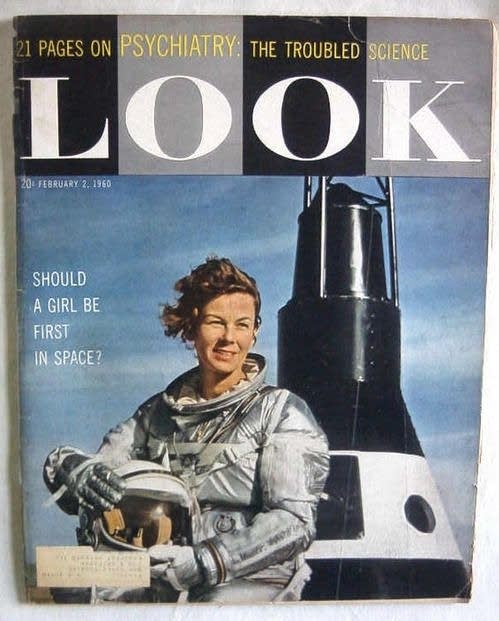

In 1959, when NASA offered her the chance to join in a centrifuge as part of a rigorous training program for women she eagerly accepted.

She undergo intense training alongside astronauts like Scott Carpenter, Alan Shepard, and Wally Schirra.

However, she understood that it would be another quarter-century before women would actually travel into space. So she wouldn’t be one of them. “I realized this from my past experiences in flying in air shows,” Skelton said.

She didn’t let this realization diminish her excitement and commitment to the training program.

“I felt it was an opportunity to try to convince (NASA) that a woman could do this type of thing and could do it well,” she said. “I think my entire association for even that brief period of time was probably the most soul-searching thing I’ve ever been involved with. To suddenly walk into the NASA compound, so to speak, and have them explain what it was they were trying to do, how they were going about it, what the problems were, you know, prior to that, prior to the first manned flight, a lot of these missiles were blowing up, and it was a very frightening thing, a touch-and-go thing. They had a tremendous job to do, and I had great respect for all of their efforts.”

People repeatedly asked her, “What makes you tick?”

Her response: “My heart makes me tick, and it’s my heart that makes me do these things, what I feel inside. As (Edmund) Hillary said, he climbed Mount Everest because it was there. I don’t think I have any better answer than that, except that everyone is built a little differently, and my heart and my will and my desires are mixed up with challenge.

“I love any kind of challenge. I love skydiving and have enjoyed that. Anything that’s challenging, usually with mechanized equipment, I find most interesting.”