Do you remember the devastating flood that hit Cambridge in 1974? Maybe you’ve heard the stories passed down through your family, or perhaps you lived through it yourself. Fifty years have gone by since the Grand River overflowed, marking the start of what would become known as “The Great Flood.”

Today, we’re here to take you through this unforgettable event, so keep scrolling to discover the full story.

Before The Great Flood

As winter’s snow melted and spring rains fell, the Grand River, typically a calm waterway, started overflowing its banks. While rivers naturally rise and fall with the seasons, the extent of this flooding took many by surprise. It soon became one of the most significant natural disasters in the area’s history, impacting lives, reshaping the landscape, and changing how communities interacted with the river that flows through them.

On May 17, 1974, the day began with bright sunshine and warmth, creating a false sense of security for many. Judge W.W. Leach, who led a provincial inquiry into the flood, noted that people were “unaware of the approaching catastrophe.”

When the rain finally arrived, it was too late to take action, as the reservoirs were already at capacity. The inquiry revealed that while warnings were issued, they did not reach everyone who needed to know, leaving many unprepared for the disaster that was about to happen.

What exactly happened

At 7 p.m., the Grand River surged through downtown Galt at an astonishing rate of 1,490 cubic meters per second, a record that still stands. In contrast, the summer low flow is just 15 m³/s. As the river swelled, dikes broke in Bridgeport and Brantford, and floodwaters swept through Paris, Caledonia, Cayuga, and Dunnville.

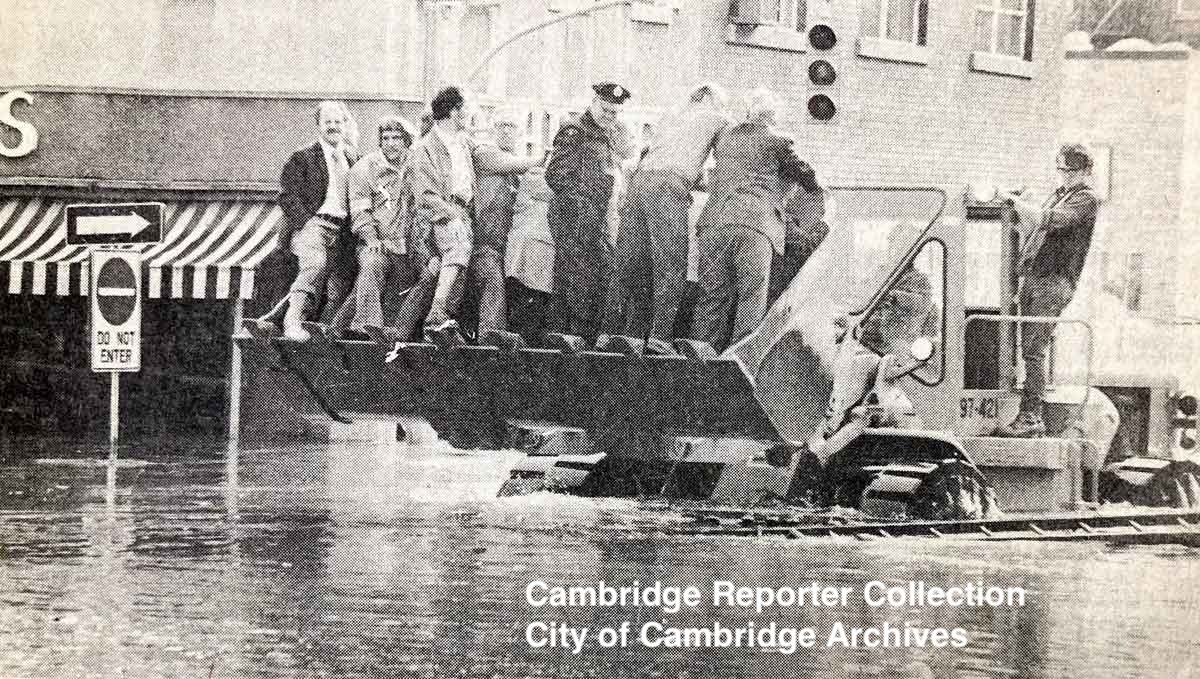

The Grand River overflowed its banks and flooded downtown Cambridge, with water levels rising more than five meters. The disaster caused $34 million in damages, but the community came together to support rescue and cleanup efforts.

Several bridges were washed away, and the flooding caused significant damage to homes, businesses, and infrastructure. The floodwaters destroyed roads and utilities, leaving thousands without electricity or access to clean water. Despite the scale of the disaster, no lives were lost, a testament to the emergency efforts led by local authorities.

The Waterloo Regional Police Service helped evacuate residents while the Region of Waterloo set up an emergency shelter. They also treated the water and tested it daily since Cambridge was under a boil water advisory.

What made it worse

Homer Watson, a renowned artist and conservationist from the Grand River area, once expressed concern about the destruction of forests, saying, “Year after year the forest was spoiled to furnish food for the saw.” He saw the cutting down of the towering “cloud-cleaving pines” as a reckless act that led to devastating floods—nature’s way of seeking revenge.

By the end of the 19th century, nearly 95% of the trees in the Grand River watershed were gone, contributing to frequent flooding. This eventually led to the creation of the Grand River Conservation Authority in the 1930s. Since then, communities and the GRCA have worked together: plant trees every spring to restore and protect the land’s health.

Moreover, the Region’s emergency planning was handled by just one person at that time. This individual coordinated everything from issuing bulletins and delivering supplies to shelters, to providing food for volunteers and assisting with rescues during times of crisis.

How Community Spirit Shined During the Great Flood

One of the most heartwarming things about the flood was the incredible unity and community spirit it brought out. People from all walks of life came together to help one another. Families opened their homes to those who had to evacuate, and volunteers worked tirelessly filling sandbags for days. This cooperation became a bright spot, showing the resilience and compassion of the community.

Adversity often leads to innovation, and this was no different. With communication difficult during the chaos, people came up with creative solutions. Ham radio operators volunteered to keep communication going, and boats were used to deliver supplies to areas cut off by the flood.