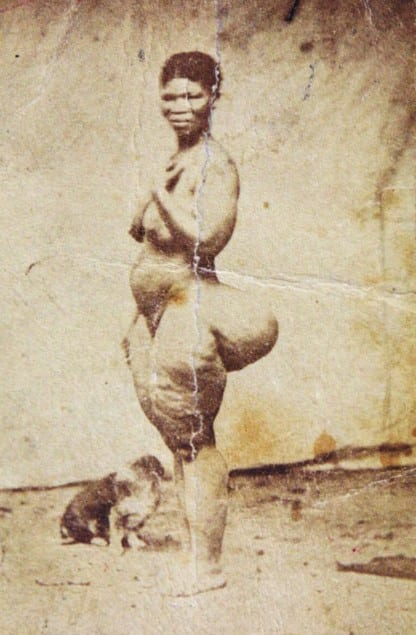

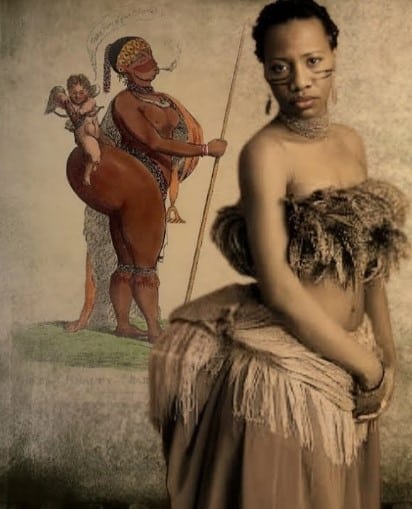

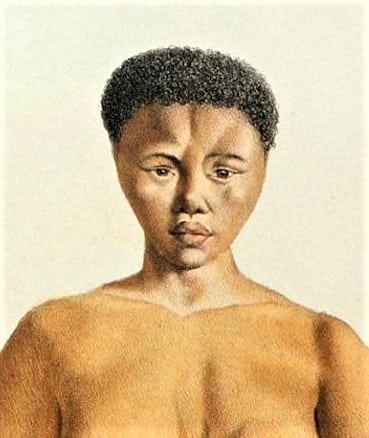

Saartjie Baartman, known as Sara Baartman, was a woman whose tragic story captured the world’s attention in the early 19th century.

Born in South Africa, she became a victim of exploitation and racial objectification when she was taken to Europe. There, she was exhibited as a curiosity because of her “unusual” physical features

Derisively nicknamed the “Hottentot Venus,” her body was subjected to public scrutiny and inhumane treatment throughout her short life.

Baartman’s early years filled with hardship and loss

Sara Baartman was born in 1789 at the Gamtoos River, now known as the Eastern Cape in South Africa. She and her family were part of the Gonaquasub group of the Khoikhoi people. Growing up on a colonial farm, Baartman and her family likely worked as servants.

Tragedy struck early in her life: her mother died when she was an infant, and her father was later killed by Bushmen while driving cattle.

During her childhood and teenage years, Baartman lived on Dutch European farms. In the 1790s, she met Peter Cesars, a free black trader who encouraged her to move to Cape Town. It’s unclear whether she left willingly, was sent by her family, or was forced to go with Cesars.

In Cape Town, Baartman worked as a washerwoman and nursemaid, first for Peter Cesars, then for a Dutch man. She eventually became a wet nurse in the household of Peter’s brother, Hendrik Cesars. It is known that she had two children, but both sadly died in infancy.

Her life darker by the contract

In 1810, 21-year-old Baartman, who could not read, was said to have signed a contract with William Dunlop, a physician and friend of the Cezar brothers.

The contract stated she would travel with the Cezar brothers and Dunlop to England and Ireland to work as a domestic servant, as slavery had been abolished in Great Britain.

Additionally, she was to be displayed for entertainment, earning a share of the profits and returning to South Africa after five years. However, the contract was fraudulent, and she remained enslaved for the rest of her life.

Dunlop led the plan to exhibit Baartman. A British legal report from November 26, 1810, included an affidavit from Mr. Bullock of Liverpool Museum, outlining the details.

“Some months since a Mr. Alexander Dunlop, who, he believed, was a surgeon in the army, came to him to sell the skin of a Camelopard, which he had brought from the Cape of Good Hope…. Some time after, Mr. Dunlop again called on Mr. Bullock, and told him, that he had then on her way from the Cape, a female Hottentot, of very singular appearance; that she would make the fortune of any person who shewed her in London, and that he (Dunlop) was under an engagement to send her back in two years…”

Lord Caledon, governor of the Cape, had given permission for the trip but later expressed regret upon learning its true purpose.

Be exhibited in Europe

Dunlop arranged for Baartman to be exhibited, with Cesars acting as the showman. Dunlop exhibited Baartman at the Egyptian Room, London. He believed he could make money because Londoners were unfamiliar with Africans and curious about Baartman’s large buttocks.

According to Crais and Scully in their well-documented book “Sara Baartman and the Hottentot Venus: A Ghost Story and a Biography, Sara was always seen as a symbol and never as a human being.

Crais and Scully allege that: “People came to see her because they saw her not as a person but as a pure example of this one part of the natural world”.

The tradition of freak shows was well established in Europe at this time, and historians have argued that this is at first how Baartman was displayed. Baartman never allowed herself to be exhibited nude, and an account of her appearance in London in 1810 makes it clear that she was wearing a garment, albeit a tight-fitting one.

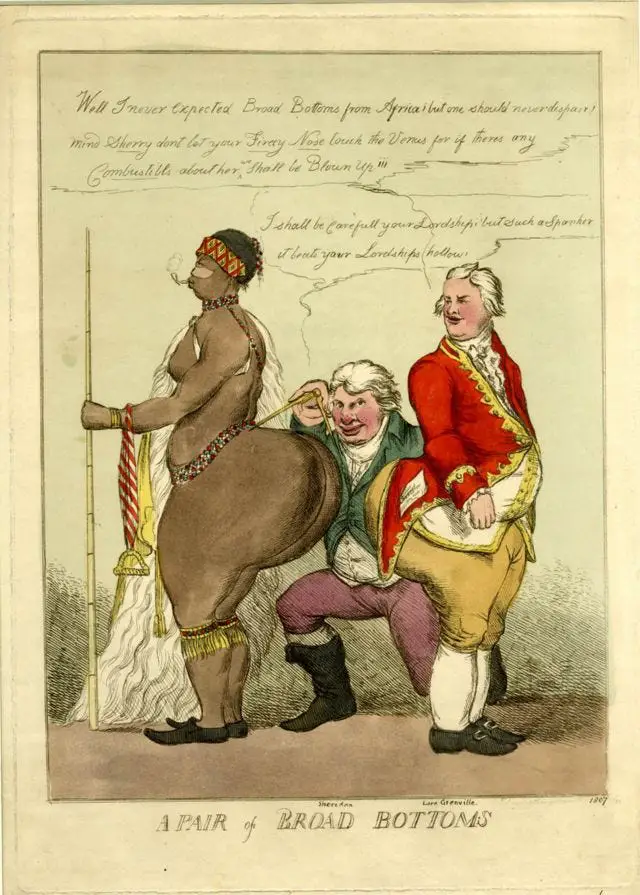

She became a subject of scientific interest, albeit of racist bias frequently, as well as of erotic projection. It is alleged she was marketed as the “missing link between man and beast”

Baartman was first exhibited in London at the Egyptian Hall in Piccadilly Circus on November 24, 1810. Her public treatment soon caught the attention of British abolitionists, who accused Dunlop and the Cezars of holding her against her will.

Despite their efforts, the court ruled against Baartman after Pieter Cezar presented a signed contract. Baartman also testified that she was not being mistreated.

The court trial’s publicity made Baartman even more popular as an exhibit. She was taken on tours throughout England and, by 1812, as far as Limerick, Ireland.

In September 1814, after four years in Great Britain, Baartman was taken to France and sold to S. Reaux, an exhibitor known for showcasing animals. He displayed Baartman in various locations around Paris, frequently at the Palais Royal.

In Paris, her exhibition became closely tied to scientific racism. French scientists were curious about her physical features, particularly whether she had elongated labia.Georges Cuvier, a leading naturalist and pioneer in comparative anatomy, was among those who examined her.

She was even depicted in several scientific paintings and was closely studied at the Jardin du Roi in March 1815.

Beyond the scientific community, she was displayed at affluent parties and private salons. Crais and Scully noted, “By the time she got to Paris, her existence was really quite miserable and extraordinarily poor”. At some points a collar was placed around her neck.

Her final years were marked by poverty, likely exacerbated by the economic depression in France after Napoleon’s defeat. This downturn meant there were fewer people willing to pay to see her

Tragic Fate

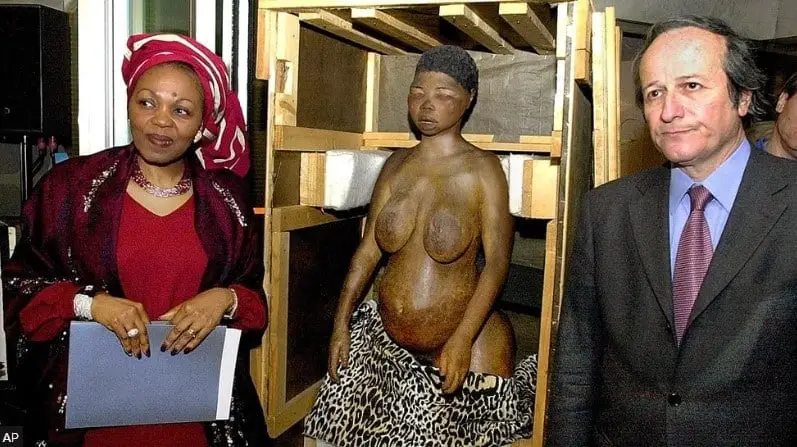

Sara Saartjie Baartman died in Paris on December 29, 1815 at aged 26 for unknown reasons. Even after her death, many parts of her body were put on display at the Musée de l’Homme in Paris, perpetuating racist ideologies about African people.

In 1827, her skull was stolen but later returned. Despite these controversies, her skeleton and skull continued to attract curiosity. Some of her remains were kept publicly displayed until 1974.

After the African National Congress (ANC) won the 1994 South African general election, President Nelson Mandela requested France to return Sara Saartjie Baartman’s remains.

After extensive legal discussions and debates in the French National Assembly, France agreed on March 6, 2002.

Her remains were repatriated to her homeland, the Gamtoos Valley, on May 6, 2002, and laid to rest on August 9, 2002, at Vergaderingskop hill in Hankey, more than 200 years after her birth.