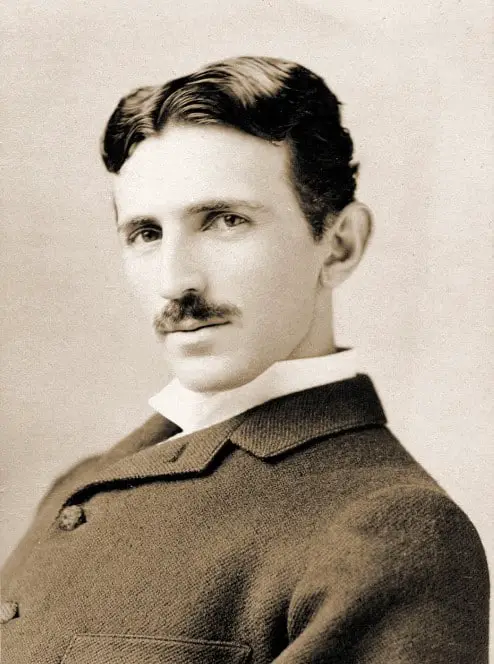

Nikola Tesla is a brilliant inventor and engineer whose groundbreaking work revolutionized the world of electricity.

He is best known for creating things like the alternating current (AC) system, which powers a lot of our world today. His inventions, like the Tesla coil and wireless electricity, still influence how we live today.

Nikola Tesla’s Journey: From Manhattan To Colorado Springs

In late 1886, Tesla met Alfred S. Brown, a Western Union superintendent, and New York attorney Charles Fletcher Peck. These two men were experienced in setting up companies and promoting inventions for profit.

Impressed by Tesla’s ideas for electrical equipment, they decided to support him financially and manage his patents. They provided him with a laboratory at 89 Liberty Street in Manhattan, where Tesla worked on improving electric motors, generators, and other devices.

As the World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893 approached in Chicago, Westinghouse enlisted Tesla’s help to provide power.

With AC electricity, Tesla lit up the fair with more light bulbs than the entire city of Chicago had. Audiences were amazed by his demonstrations, including a wirelessly powered electric light

Tesla faced challenges along the way. In 1895, a fire destroyed his Manhattan lab, wiping out his notes and prototypes. Then, in 1898 at Madison Square Garden, his wireless boat control demo was called a hoax by many.

Despite setbacks, he shifted focus to wireless power transmission, believing it could revolutionize global electricity and communication. To test his theories, he built a lab in Colorado Springs.

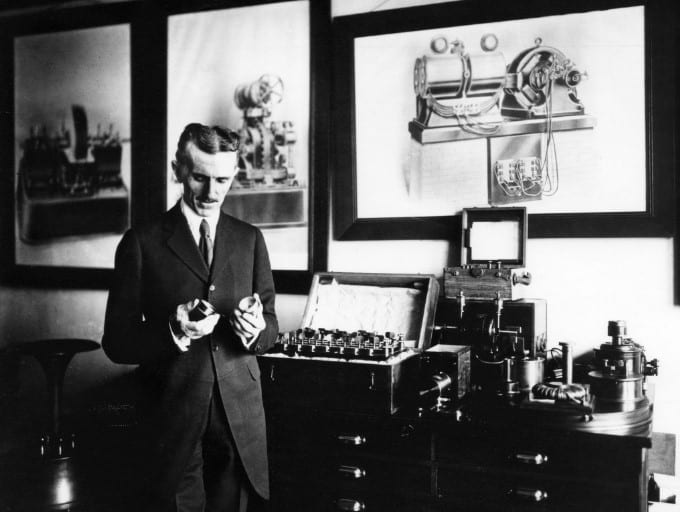

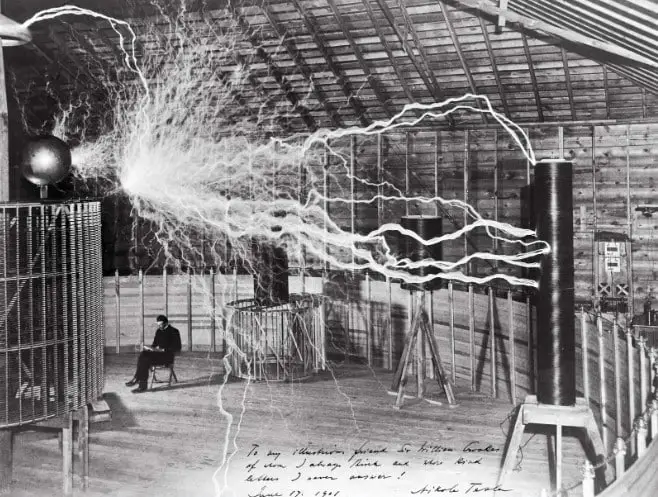

Some of rare photos of Nikola Tesla in his Colorado Springs laboratory, 1899

Publicity photo of Serbian-American inventor Nikola Tesla in December 1899 sitting in his laboratory in Colorado Springs next to his magnifying transmitter high voltage generator while the machine produced huge bolts of electricity.

This image was created by Century Magazine photographer Dickenson V. Alley using “trick photography” via a double exposure. The electrical bolts were photographed in a darkened room.

The photographic plate was exposed a second time with the equipment off and Tesla sitting in the chair. In his Colorado Springs Notes Tesla admitted the photo was a double exposure:

“To give an idea of the magnitude of the discharge the experimenter is sitting slightly behind the “extra coil”. I did not like this idea but some people find such photographs interesting. Of course, the discharge was not playing when the experimenter was photographed, as might be imagined!”

This photo was published in Century Magazine, June 1900, with caption: “The photograph shows three ordinary incandescent lamps lighted to full candle-power by currents induced in a local loop consisting of a single wire forming a square of fifty feet each side, which includes the lamps, and which is at a distance of one hundred feet from the primary circuit energized by the oscillator. The loop likewise includes an electrical condenser, and is exactly attuned to the vibrations of the oscillator, which is worked at less than five per cent. of its total capacity.”

This photo, taken by Carl Duffner, shows one of Nikola Tesla’s assistants at the variable-inductance crank in the primary circuit of the large Colorado Springs experimental station oscillator in 1899.

The primary winding was a heavy, two-turn, multi-strand cable measuring 50 feet in diameter.

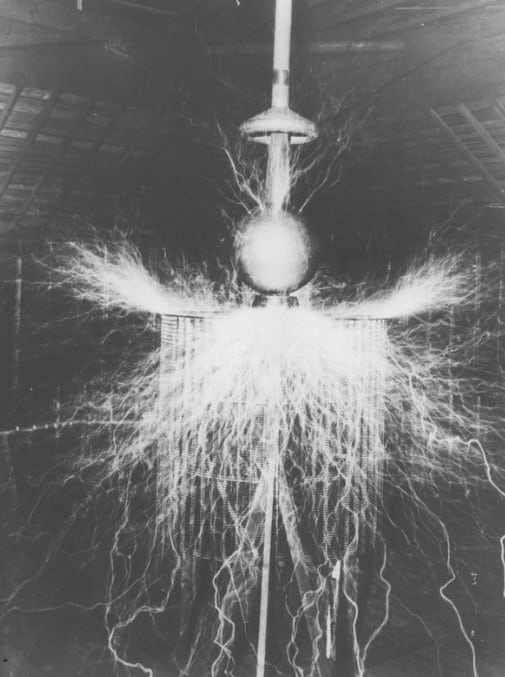

This image from Colorado Springs illustrates the oscillator’s ability to generate electricity of millions of volts and a frequency of 100,000 alternations per second.

It was featured in Century Illustrated Magazine in June 1900, highlighting Tesla’s groundbreaking work on increasing human energy.

“Here is a photo from Colorado Springs, Colorado (in 1899), illustrating the capacity of the oscillator to create electricity of millions of volts and a frequency of 100,000 alternations per second.

The ball shown in the photograph, covered with a polished metallic coating of twenty square feet of surface, represents a large reservoir of electricity, and the inverted tin pan underneath, with a sharp rim, a big opening through which the electricity can escape before filling the reservoir.

The quantity of electricity set in movement is so great that, although most of it escapes through the rim of the pan or opening provided, the ball or reservoir is nevertheless alternately emptied and filled to over-flowing (as is evident from the discharge escaping on the top of the ball) one hundred and fifty thousand times per second”.