You might be familiar with the movie Castaway, starring Tom Hanks. The term “castaway” means someone who is shipwrecked or lost in a remote place.

In the film, Hanks was stranded on an island; in real life, Poon Lim faced an even more daunting challenge—being adrift in the open ocean.

Imagine being in the middle of nowhere. How would you survive when your supplies ran out? What if no one could hear you scream for help? Poon Lim faced these terrifying challenges head-on.

Scroll down to discover how he overcame these hardships.

How Lim became a steward on the SS Benlomond

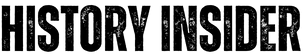

Poon Lim, born in 1918 on the Chinese island of Hainan, grew up during a tumultuous period as Japan sought to dominate China in the 1930s.

Fearing for his son’s safety and the potential for him to be drafted into the Chinese army, Lim’s father decided it was best for him to leave the country. Seeking a new path, Lim joined the British Merchant Navy as a cabin boy, following his brother into a life at sea.

Life aboard the British Merchant Navy ships provided Lim with a respite from the horrors of Japanese occupation. However, it introduced new challenges. Asian crew members, including Lim, faced severe discrimination and physical abuse from European officers.

This harsh treatment led Lim to leave the Merchant Navy in 1937. He relocated to Hong Kong, where he began working as a mechanic, seeking stability and a fresh start away from the sea.

The outbreak of World War II in 1939 led to significant manpower shortages for the British Navy. In a bid to attract more recruits, the British improved working conditions on their ships. In 1941, as Japan prepared to strike Hong Kong, Lim saw an opportunity to escape the impending invasion.

Despite his previous negative experiences, he decided to return to sea as a steward on the SS Benlomond, hoping for better conditions and a safer environment.

He got struck in the South Atlantic Ocean

On November 10, 1942, Poon Lim boarded the British-armed merchant ship SS Benlomond as the second mess steward. The ship departed from Cape Town, South Africa, heading to Paramaribo, Brazil, with a crew of 54 men. Despite being armed, the vessel was slow and sailed without escort.

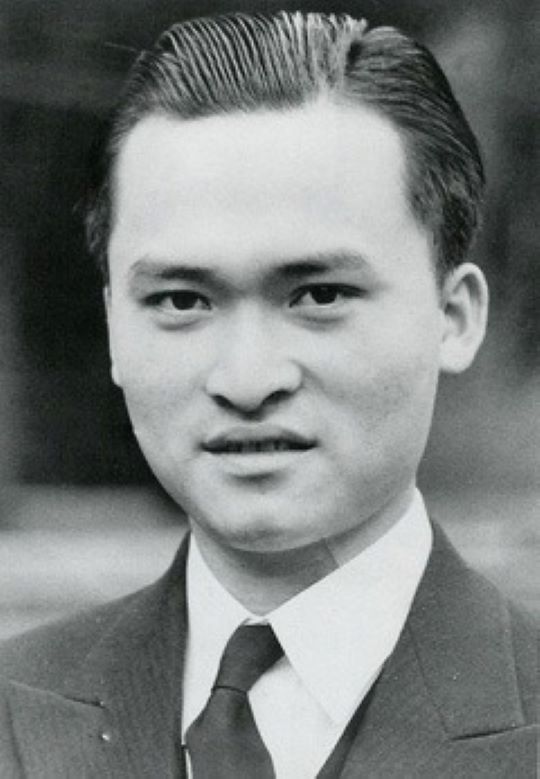

Just 13 days later, on November 23, the Benlomond was spotted by the German U-172 U-boat 750 miles east of Belém, Brazil. This area was considered safe, far from European military zones. Nevertheless, the U-boat launched two torpedoes, sinking the ship in just two minutes.

Lim was pulled underwater along with most of the crew but managed to surface. He saw five crew members in a raft and began swimming towards them. However, the U-boat surfaced and took the men aboard, likely for interrogation.

After some time, the five men were placed back on their raft. Just as Lim was about to reach them, the U-boat submerged again, causing the surrounding sea to churn. When the water calmed, both the raft and the crewmen were gone. Lim was left alone in the vast ocean.

How he survived 133 days alone at sea

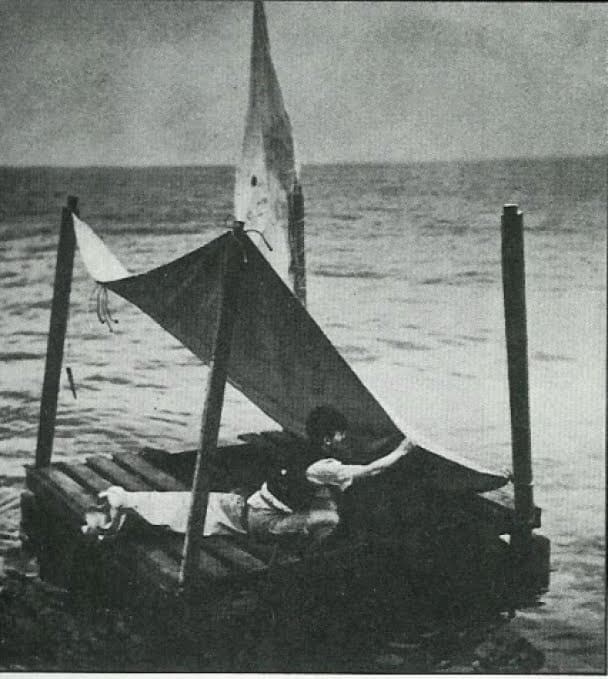

After a few hours of swimming, Poon Lim found a small wooden raft with limited supplies, including water, hardtack, chocolate, pemmican, and other essentials. Surrounded by undrinkable seawater, he quickly adapted to his new reality.

He built a canopy to protect himself from the sun and collected rainwater for drinking. The initial food supplies helped, but he soon had to rely on his ingenuity to survive.

Fishing, catching seabirds, and collecting rainwater became crucial for his sustenance. Lim, not being a strong swimmer, secured a rope from the raft to his wrist to prevent himself from drifting away if he fell into the sea.

He crafted a fishhook from a flashlight spring, used hemp rope for the fishing line, and baited it with crushed hardtack. He later improved his tools by using a nail from the raft to make a stronger fishhook, which allowed him to catch larger fish.

Lim’s resourcefulness didn’t stop there. He used parts of a pemmican can to create an improvised knife and repurposed an iron key from the water tank as a multi-purpose tool.

When birds landed on his raft, he captured them for food, preserving the meat by soaking it in seawater and drying it on the deck. This method effectively created jerky and ensured he had a steady food supply.

Sharks were a significant threat, but Lim adapted his fishing techniques for defense. He successfully caught a shark using bird remains as bait.

To protect his hands, he braided his fishing line to double its thickness and wrapped his hands in canvas. When a shark attacked after being pulled onto the raft, Lim used a water container to beat it and drank its liver blood to compensate for the lack of fresh water.

He was finally saved and recovered

Poon Lim faced numerous challenges during his time adrift in the Atlantic Ocean. During his time adrift, he encountered a few people in the ocean and called out for help in English. Sadly, most ignored his pleas, and some even mocked him. Lim believed he wasn’t rescued sooner because he was Asian.

Despite every reason to give up, he continued to fight for his life. His resilience is truly inspiring. Could you do the same in such dire circumstances?

Finally, in April 1942, three Brazilian fishermen rescued Lim. They found him nine nautical miles off the coast of Pará. He was so weak and had lost 20 pounds that the fishermen had to help him off the raft.

Due to the language barrier, Lim couldn’t share his harrowing story until three days after reaching land. It was only then he learned he was the sole survivor of the SS Benlomond. The ship’s captain, eight gunners, and 43 officers and men had all perished.

After spending 14 days in a Brazilian hospital, Lim was deemed fit to travel and returned to Britain, where he was awarded the British Empire Medal for his bravery. His survival story became a crucial part of Royal Navy survival manuals and a British Ministry of Information film about Chinese war efforts.

Later, Lim moved to the United States, where he gained citizenship with the help of Senator Warren Magnuson. He lived the rest of his life in Brooklyn, New York, until his death in 1991 at the age of 72.

Lim still holds the record for the longest time a single person has survived being lost at sea in a life raft. Reflecting on his record, he once said, “I hope no one will have to break it.”