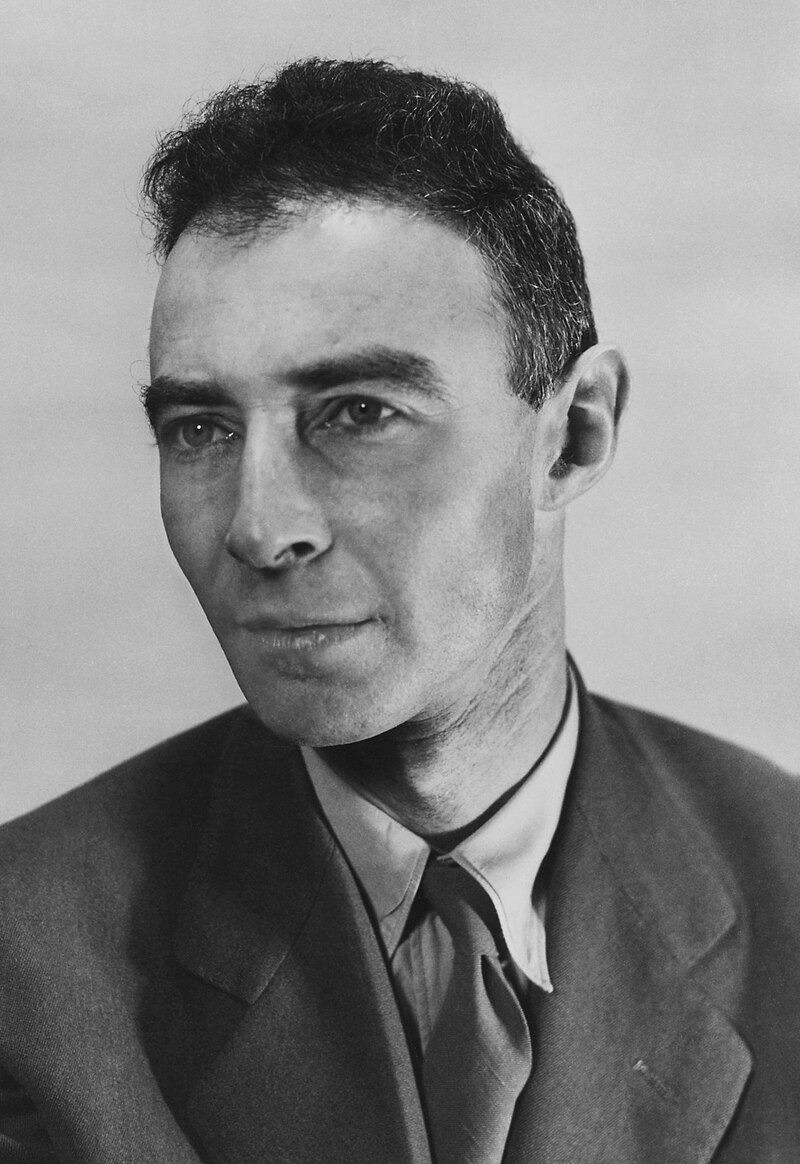

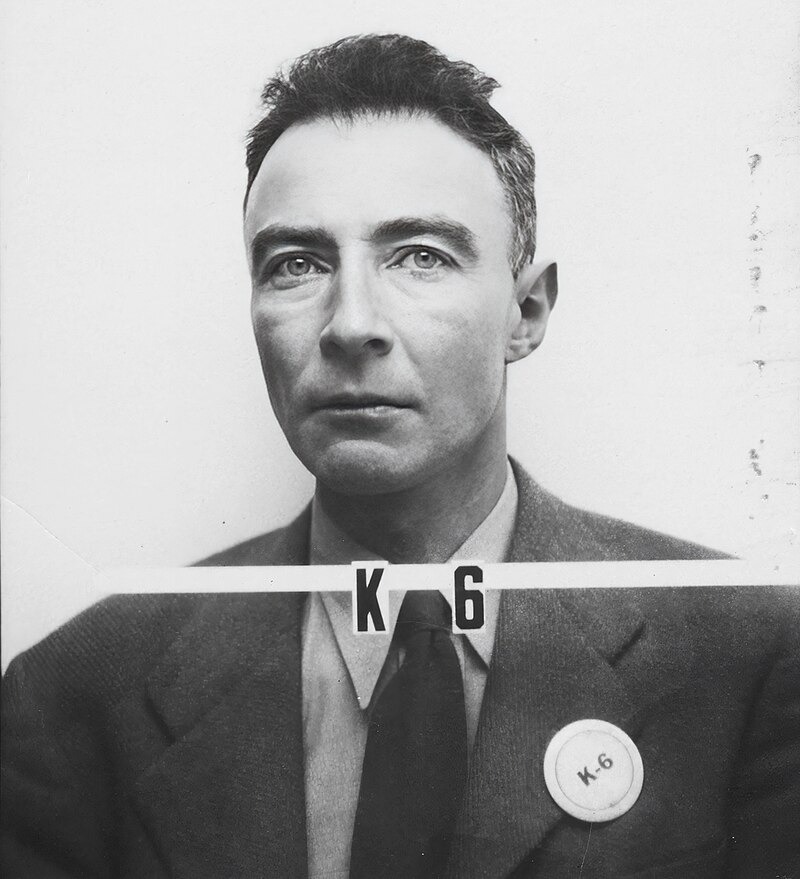

Robert Oppenheimer, celebrated as the “Father of the Atomic Bomb,” played a pivotal role in shaping modern warfare through his leadership of the Manhattan Project.

Yet, despite his immense contribution to ending World War II, Oppenheimer’s legacy became clouded during the Cold War.

In 1954, amid growing political paranoia and the hunt for Communist sympathizers, Oppenheimer was blacklisted and stripped of his security clearance.

This marked the fall of a man who had helped change the course of history. But why did the U.S. turn its back on one of its greatest minds?

Let’s explore the complex reasons behind Oppenheimer’s blacklisting, his moral struggle with nuclear weapons, and the lasting impact of his story.

The Manhattan Project and the Creation of the Atomic Bomb

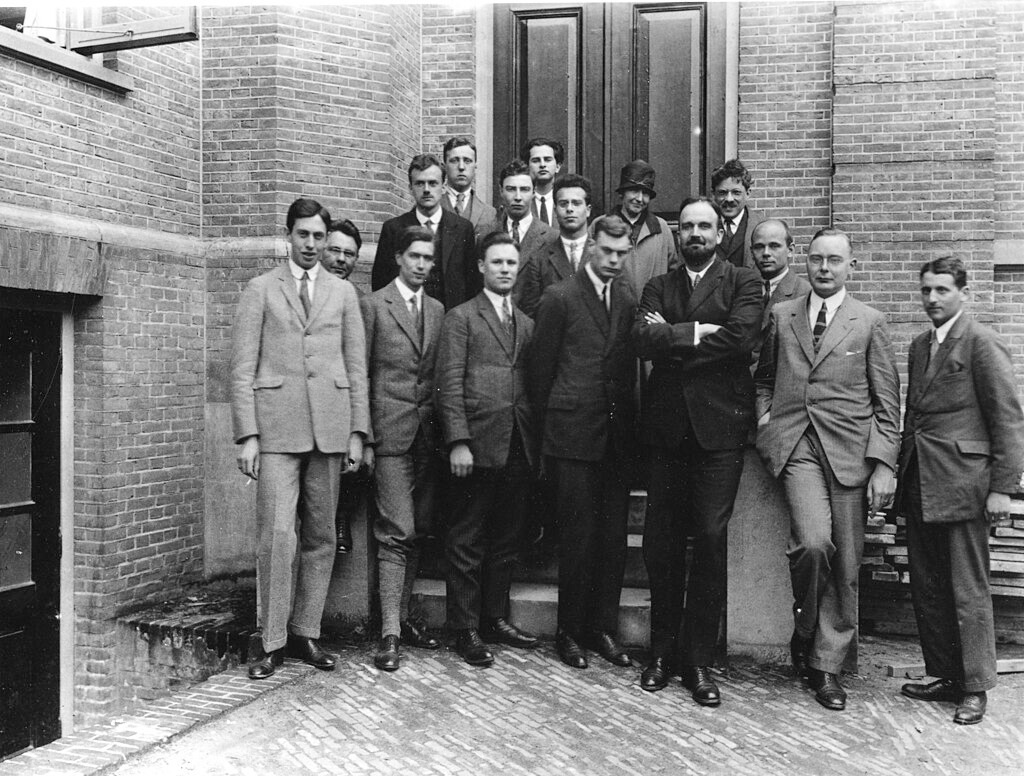

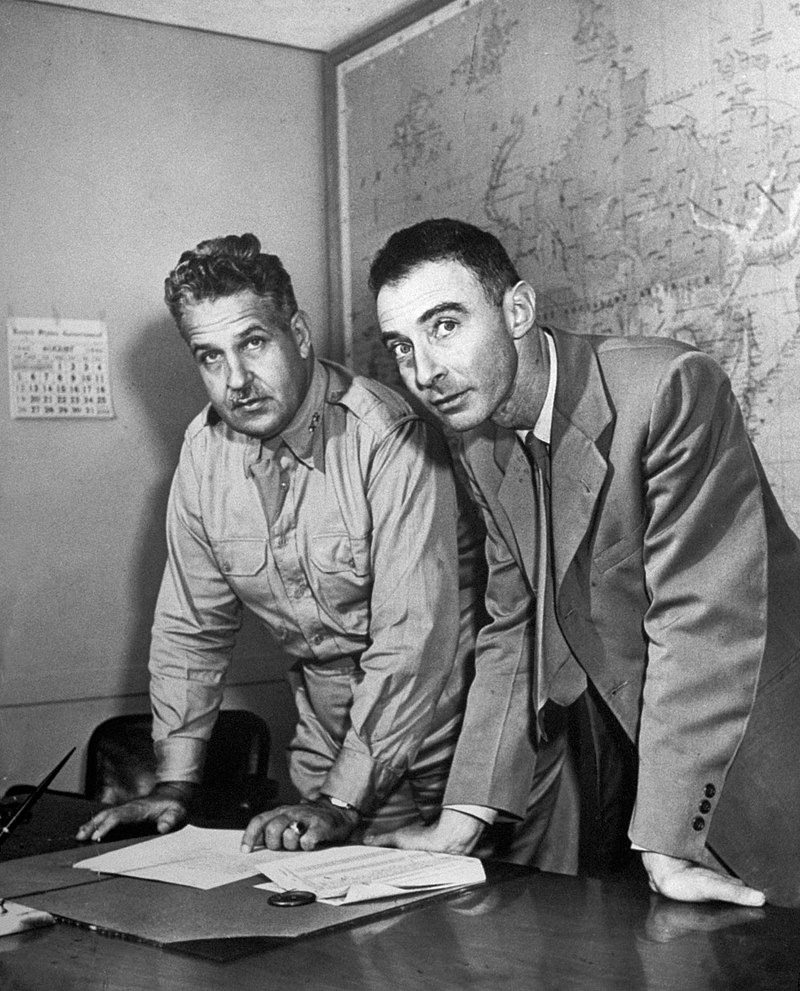

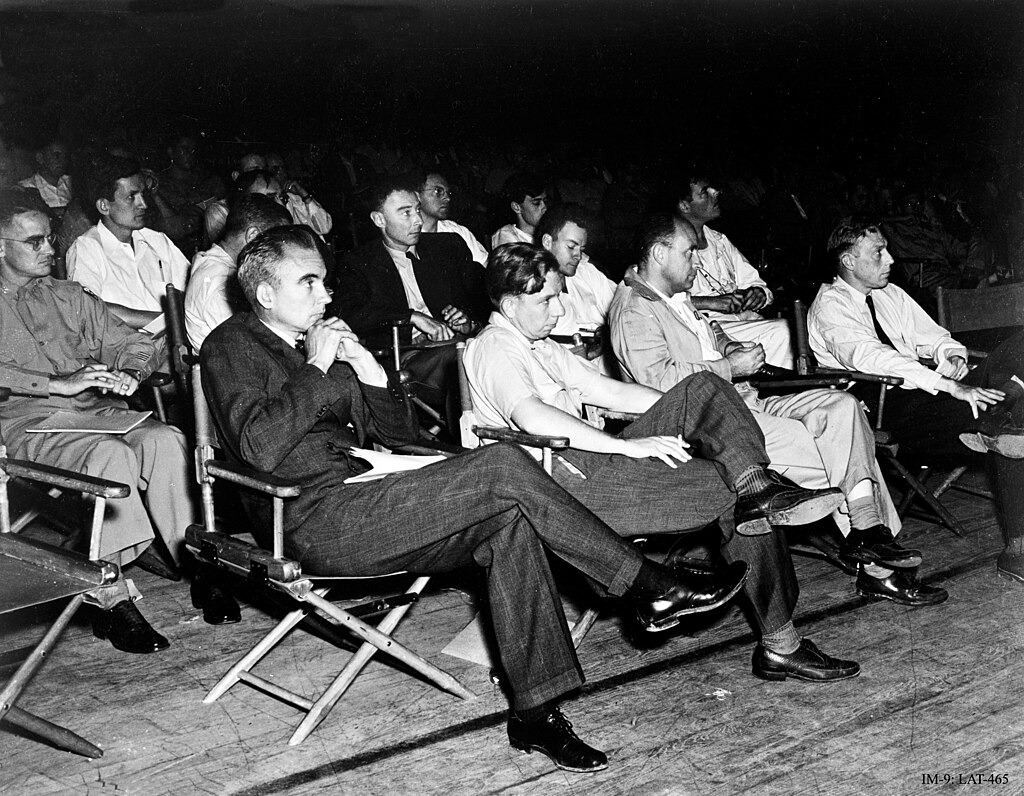

Robert Oppenheimer’s involvement in the creation of the atomic bomb began during World War II when he was appointed to lead the top-secret Manhattan Project.

This initiative sought to develop nuclear weapons to end the war and prevent Nazi Germany from acquiring such devastating power first.

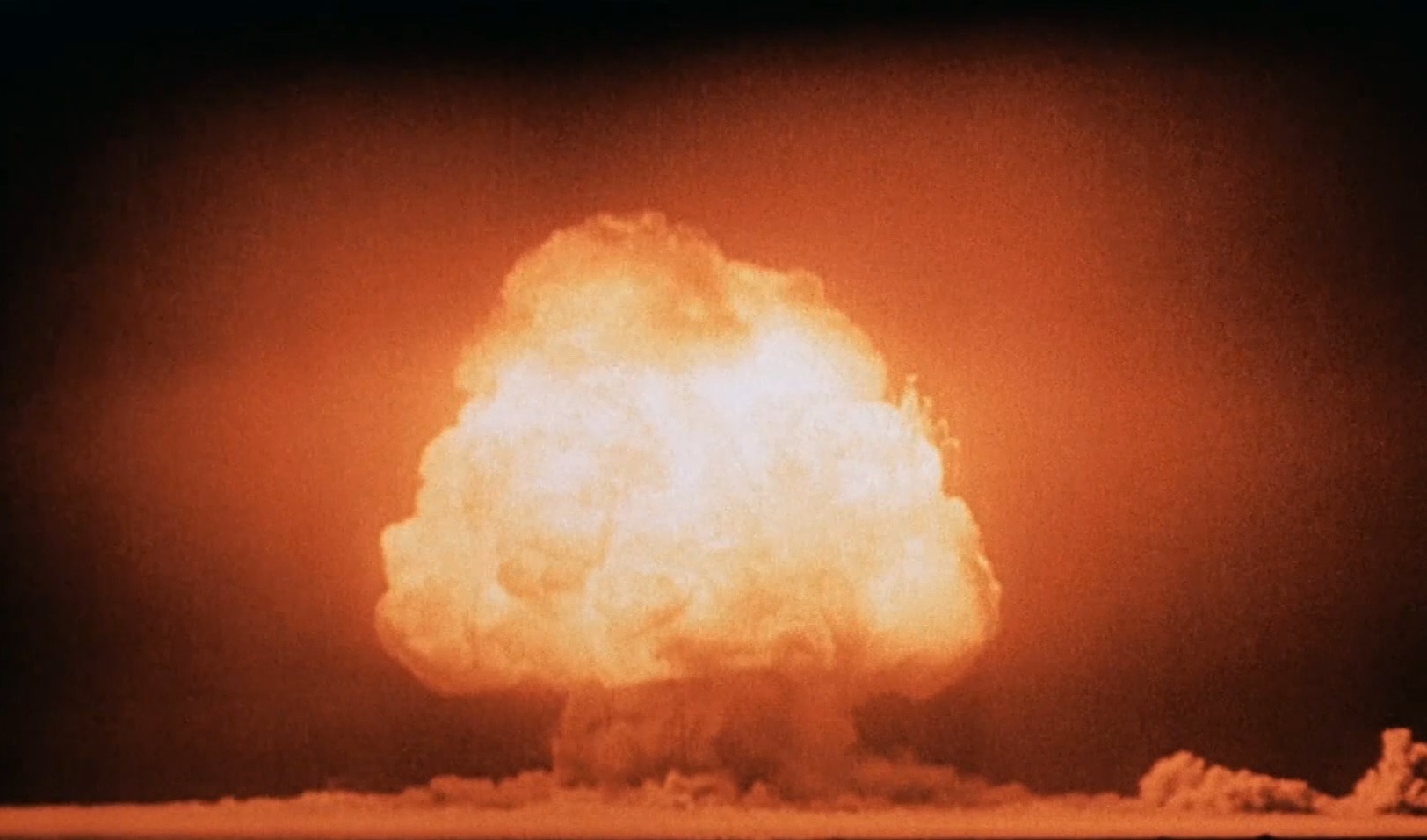

On July 16, 1945, the first successful test of the atomic bomb occurred at the Trinity site in New Mexico.

Oppenheimer, watching from a distance, famously quoted the Bhagavad Gita, “Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds.”

This is when he felt a sense of achievement, mixed with the realization of the destructive power he had helped unleash.

Just weeks later, the U.S. dropped two atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, leading to Japan’s surrender and the end of World War II.

However, the success of the bomb came with moral dilemmas that would haunt Oppenheimer for the rest of his life.

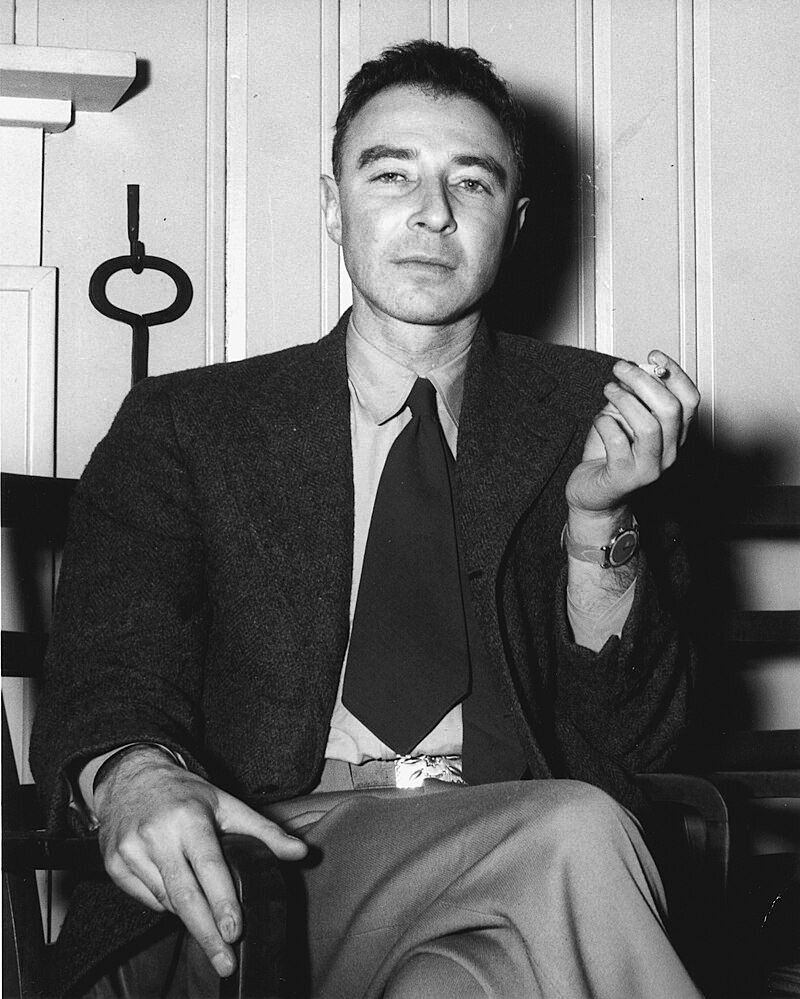

Oppenheimer’s Moral Struggle

After the bombings, Oppenheimer was filled with conflicting emotions. While he had played a key role in ending the war, the scale of destruction caused by the bombs weighed heavily on him.

He began advocating for international controls on nuclear weapons, fearing that unrestricted development would lead to a global catastrophe.

In a meeting with President Harry S. Truman in 1945, Oppenheimer expressed his deep concern, saying he felt he had “blood on his hands.”

Truman, who had authorized the bombings, dismissed Oppenheimer’s concerns, telling him that the responsibility for the deaths was his, not Oppenheimer’s.

This interaction marked the beginning of Oppenheimer’s uneasy relationship with the U.S. government.

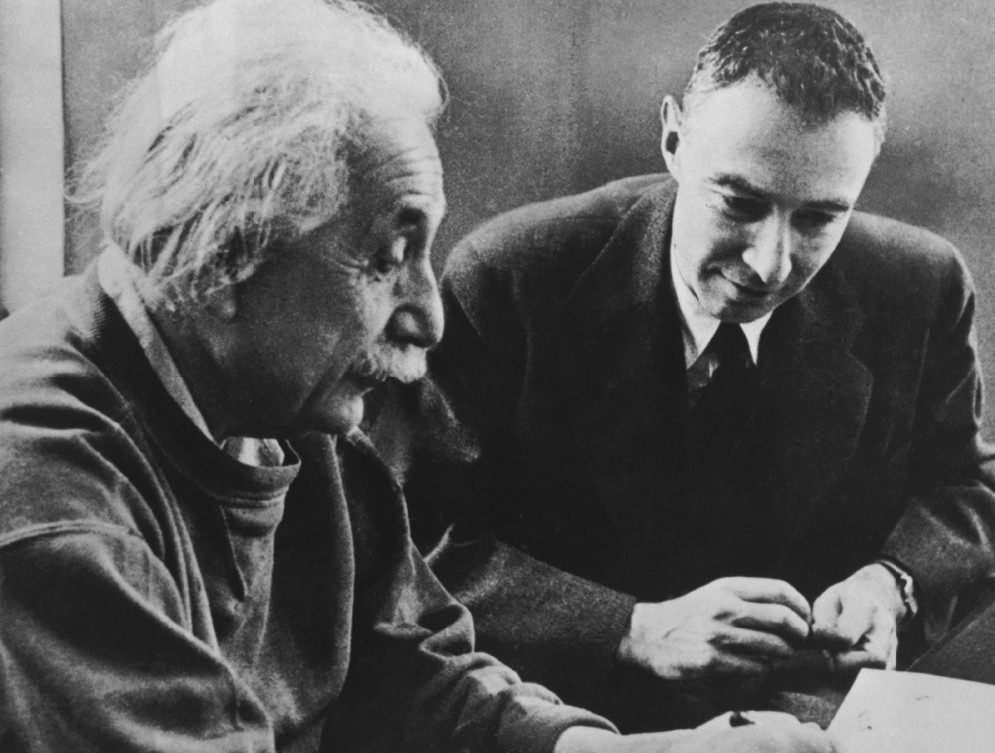

The Cold War Tensions: Opposing the Hydrogen Bomb

As the Cold War intensified and the arms race with the Soviet Union escalated, the U.S. began developing the hydrogen bomb, an even more powerful weapon than the atomic bomb.

Oppenheimer opposed this new development. He feared that the H-bomb would only push the world closer to nuclear annihilation.

This made him a target during the height of McCarthyism, a period of intense anti-Communist sentiment in the U.S.

Oppenheimer’s opposition to the hydrogen bomb was seen as a threat to national security by some, and his past associations with Communist friends further fueled suspicion.

The 1954 Security Hearing: Oppenheimer’s Blacklisting

In 1954, Oppenheimer faced a security clearance hearing led by the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC). The hearing, which many historians now view as flawed, questioned Oppenheimer’s loyalty to the United States.

His ties to individuals associated with Communism and his resistance to the H-bomb led to accusations that he might be a security risk.

The hearing concluded with Oppenheimer being stripped of his security clearance, effectively ending his influence on U.S. nuclear policy. He was branded as untrustworthy, and his career never fully recovered.

Legacy: A Black Mark Reversed

For decades, Oppenheimer’s blacklisting cast a shadow over his legacy. However, in 2022, 68 years after the initial hearing, the U.S. government formally reversed the decision.

The Department of Energy acknowledged that the investigation against Oppenheimer had been deeply flawed and driven by Cold War fears rather than evidence of wrongdoing.

Today, Oppenheimer is remembered not only as the father of the atomic bomb but also as a scientist who sought to reckon with the moral implications of his creation. He warned of the dangers of nuclear proliferation long before others took notice.