In the early 20th century, New York City faced a terrifying public health crisis—tuberculosis. Known as the “white plague,” TB was the city’s leading cause of death, especially in crowded urban areas.

In response, city officials devised a unique solution that would not only safeguard children’s health but also ensure their education. Thus, the concept of open-air classrooms was born.

These outdoor classes offered a creative way to combat disease, and the results were so promising that they spread to cities across the country.

Let’s explore how NYC’s innovative open-air schools became a crucial tool in the fight against tuberculosis.

The Tuberculosis Crisis in New York City

At the turn of the 20th century, tuberculosis was claiming more lives than any other disease in New York City. Known as the “captain of the men of death,” the disease thrived in crowded, poorly-ventilated areas.

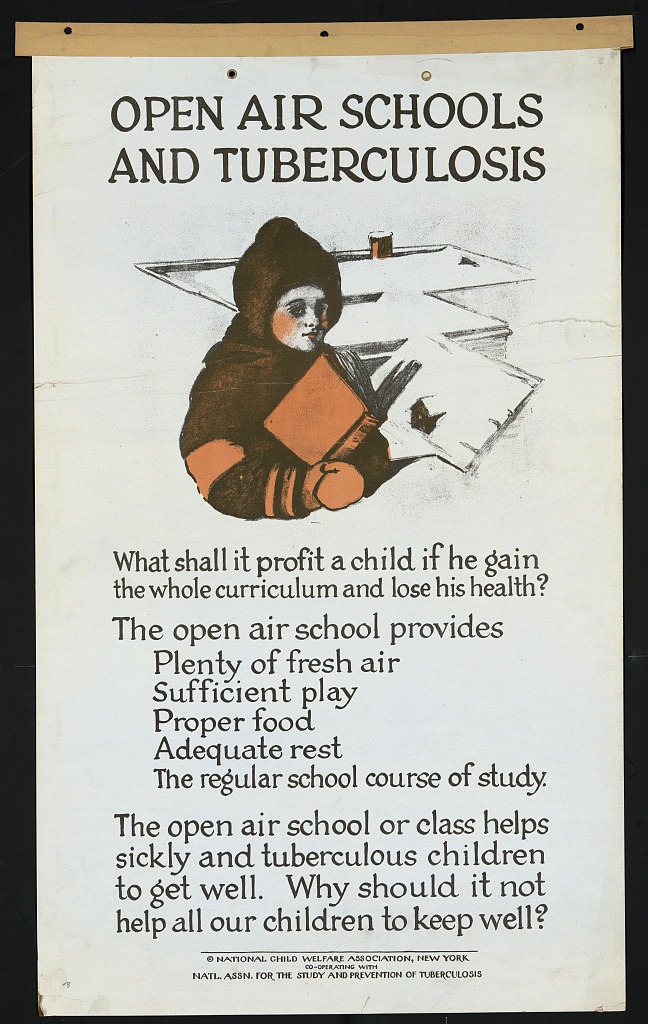

Public health measures, such as campaigns against spitting and the construction of well-ventilated buildings, began to emerge, but for schoolchildren, there was a particular challenge: how to safely provide education while protecting their health.

By 1908, doctors understood that fresh air and sunlight could help prevent and manage TB, even though an effective cure would not be developed until the 1940s.

This understanding led to the idea of outdoor education, a concept that would quickly gain traction in a densely populated metropolis like New York.

The Birth of Open-Air Classrooms

The open-air classroom movement began in Germany in the early 1900s, but New York was one of the first American cities to adopt the idea.

The goal was simple: create classrooms with better ventilation, abundant natural light, and as much exposure to fresh air as possible.

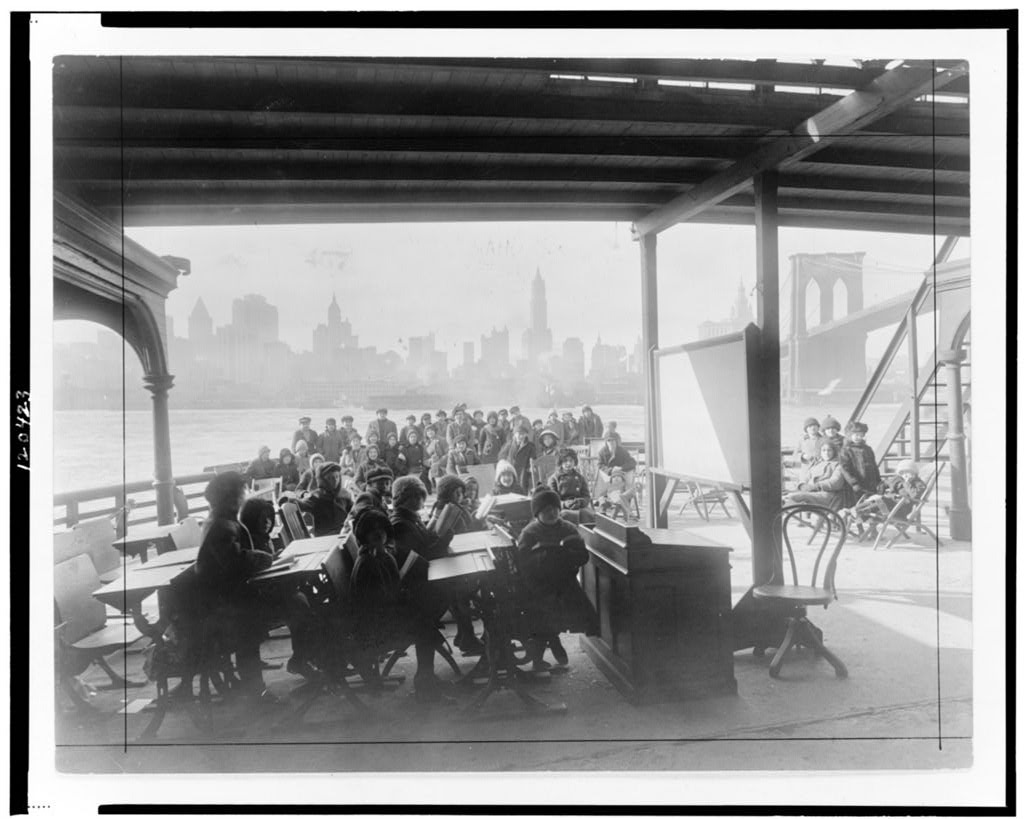

In 1908, a school for children with tuberculosis opened on a ferryboat docked along the East River, and it quickly became a model for other open-air schools.

Soon, other schools adopted similar methods, setting up rooftop classrooms and building outdoor spaces in schoolyards.

Public health officials believed that children in cramped homes or predisposed to illness could benefit from such environments—and they were right.

The city’s first large-scale experiment in outdoor education was funded in 1909 when $6,500 was set aside for the construction of open-air classrooms.

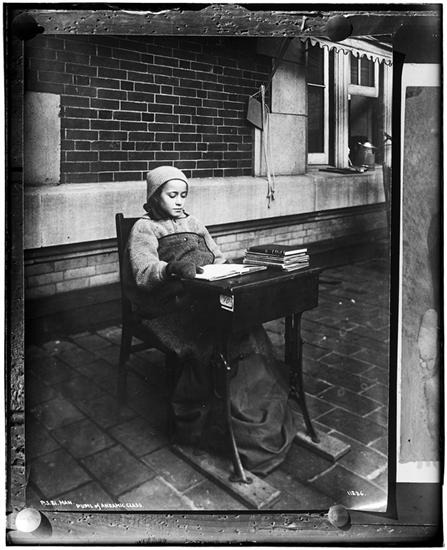

Schools in Chelsea and on Carmine Street became pioneers of this movement, holding “open-window” classes where students wore their outdoor clothing during lessons to protect against the cold.

Open-Air Classes in Practice

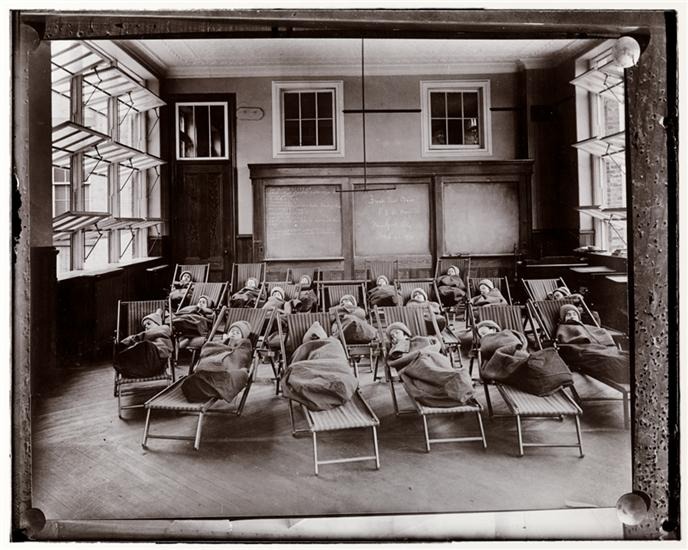

Open-air schools thrived on the philosophy that prevention was better than cure. Even though no additional feeding or special rest periods were provided for the children, the benefits of being outdoors were seen as essential to combatting TB.

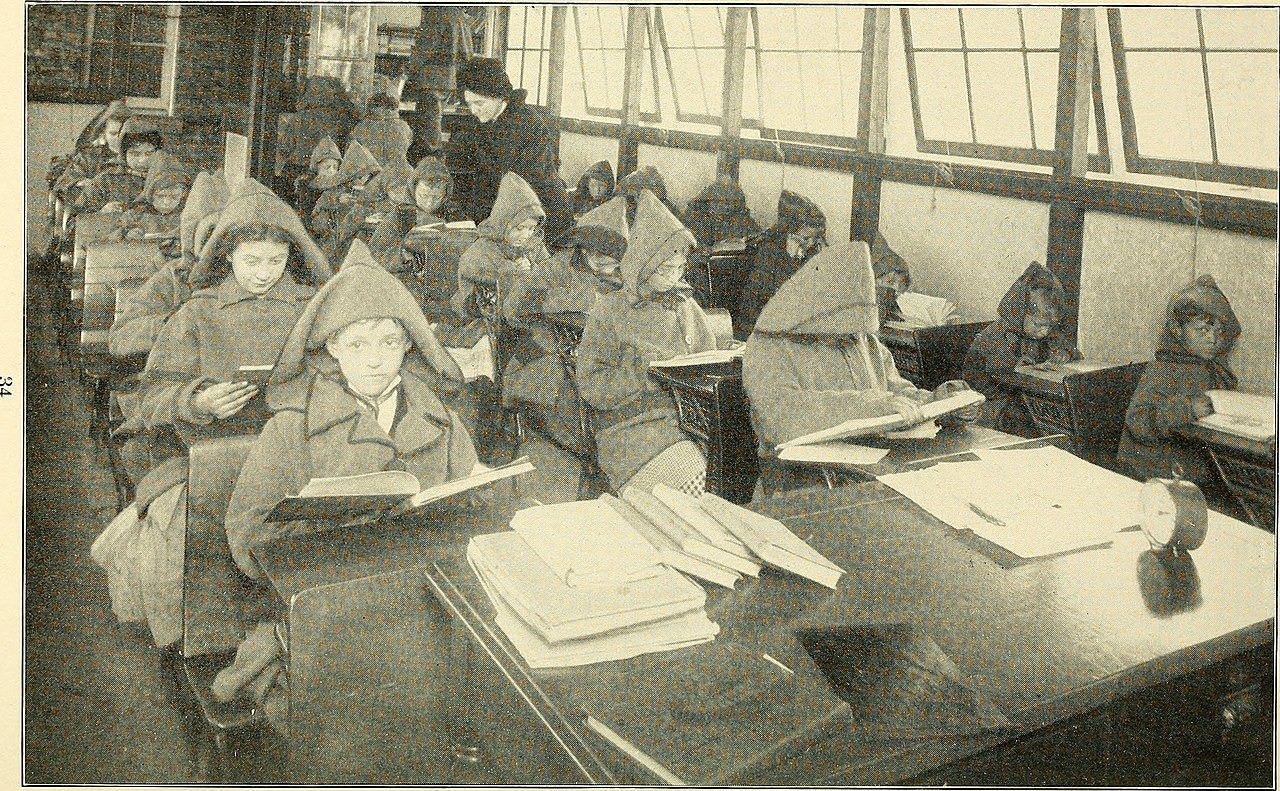

Classrooms were set up on school rooftops with walls of windows to allow continuous ventilation.

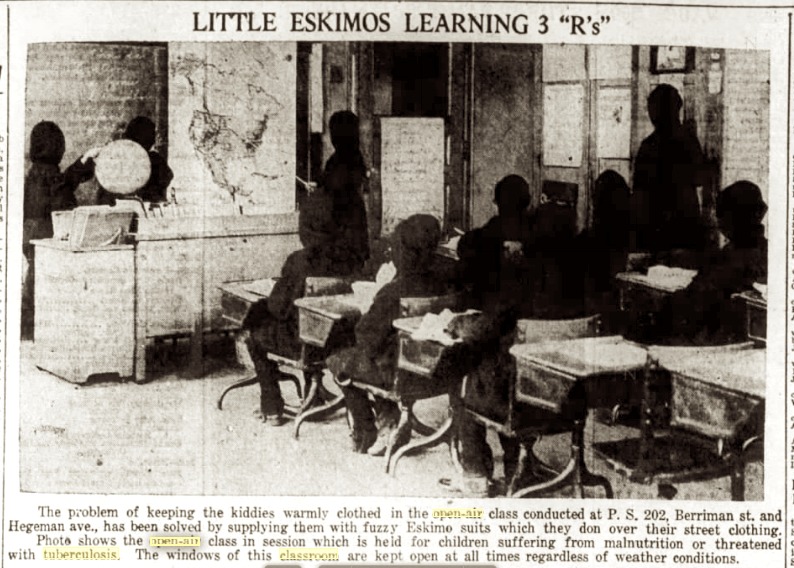

Children wore street clothes or sat in “sitting-out bags,” which were large blankets meant to keep them warm. In some schools, like Brooklyn’s Friends School, even kindergarteners attended lessons outdoors.

As temperatures dropped, schools provided special “Eskimo suits,” or parkas, to keep the children warm during the colder months. These unique garments became a familiar sight, allowing students to continue their education safely despite the cold.

The Success of Open-Air Schools

The success of New York City’s open-air schools was noticed. Public health officials began to expand the idea to other parts of the country, with cities like Chicago, Cleveland, and Boston launching their own outdoor classrooms.

The results were promising. Open-air education not only reduced the spread of tuberculosis but also led to improvements in student attendance and overall health.

Even “normal” pupils—those not afflicted with TB—benefited from these fresh-air environments, proving that clean air and proper ventilation had universal benefits for all students.

By the early 1930s, however, open-air schools began to decline. TB was no longer the terrifying public health threat it once was, and new diseases like polio shifted the focus of health officials.

While the movement eventually faded, its impact on educational methods and public health strategies remained significant.