The photo “No Dog Biscuits Today” captures a poignant moment between a sad dog and its owner in London during 1939. This image, taken by an unknown photograph, reflects the deep sorrow of the pet owner.

The line “No dog biscuits today” highlights the scarcity of goods and the struggles faced by pet owners at the time. It’s one of signs for the beginnings of The British Pet Massacre of 1939.

The event is a horrific, shocking chapter in the story of World War II. During this time, over 400,000 dogs and cats—about a quarter of England’s pet population—were euthanized in less than a week. The government made this heartbreaking decision to conserve animal food for humans to prepare for World War II food shortages.

Pet owners, having no choice, lined up for half a mile outside shelters to kill their pets. Crematoriums became overwhelmed with the number of bodies they couldn’t process at night due to blackout orders.

With limited cemetery space, half a million pets were buried in a single meadow, leading to an estimated total of 750,000 pets euthanized. However, in the middle of the pet-culling mayhem, some people tried their best to save their pets.

The greatest threat to pets during this time was not from bombs, but from food shortages. There was no food ration for cats and dogs.

What really happened?

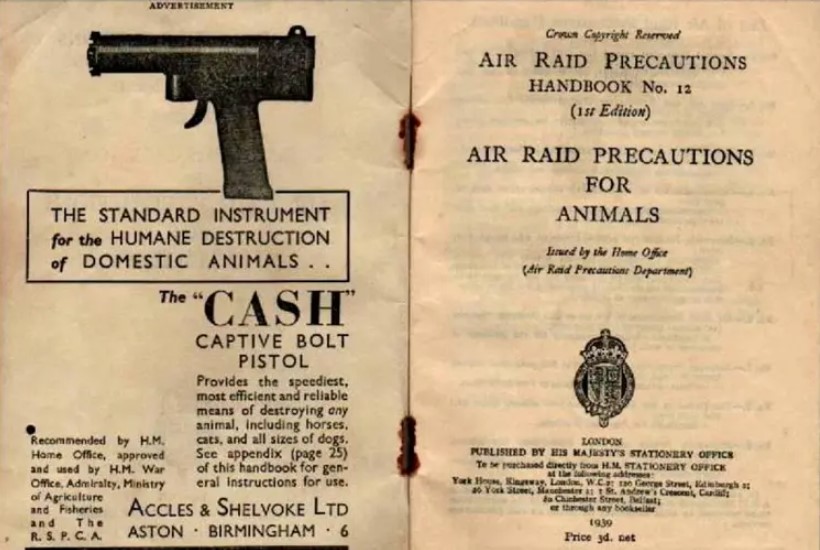

In the summer of 1939, just before World War II erupted, the National Air Raid Precautions Animals Committee (NARPAC) was established to address what would happen to pets in the face of food shortages and bombings.

They issued guidelines known as “Advice to Animal Owners”, which warned pet owners about the tough choices ahead. The British government was concerned that with food rationing, people might either share their limited rations with their pets or abandon them to starve, a grim scenario they wanted to prevent.

The government, in a bid to manage the looming crisis of food shortages during WWII, recommended that people euthanize their healthy pets. This advice was included in public brochures and spread across major newspapers and BBC broadcasts.

The pamphlet said: “If at all possible, send or take your household animals into the country in advance of an emergency.” It concluded: “If you cannot place them in the care of neighbors, it really is kindest to have them destroyed.”

Clare Campbell, author of Bonzo’s War: Animals Under Fire 1939–1945, referred to this as “a national tragedy in the making.” The public, already grappling with fears of wartime scarcity, were confronted with the heartbreaking task of deciding their pets’ fate.

Campbell also recalls a story about her uncle. “Shortly after the invasion of Poland, it was announced on the radio that there might be a shortage of food. My uncle announced that the family pet Paddy would have to be destroyed the next day.”

What did people do at that time?

After war was declared on September 3, 1939, a wave of fear swept through pet owners across Britain.

Many rushed to veterinary clinics and animal shelters, seeking to have their pets euthanized in the face of uncertain times. Animal hospitals, like the PDSA, were overwhelmed by the influx.

The charity’s founder, Maria Dickin, noted, “Our technical officers called upon to perform this unhappy duty will never forget the tragedy of those days.”

Although animal charities like the PDSA, RSPCA, and veterinarians opposed the mass killing of pets, many were distressed by the number of abandoned animals left behind by their owners.

In the midst of this sorrow, heart-wrenching “In Memoriam” notices began to appear, like one in Tail-Wagger Magazine that expressed the grief of losing a beloved pet.

“Happy memories of Iola, sweet faithful friend, given sleep September 4th 1939, to be saved suffering during the war. A short but happy life – 2 years, 12 weeks. Forgive us little pal,” the person said.

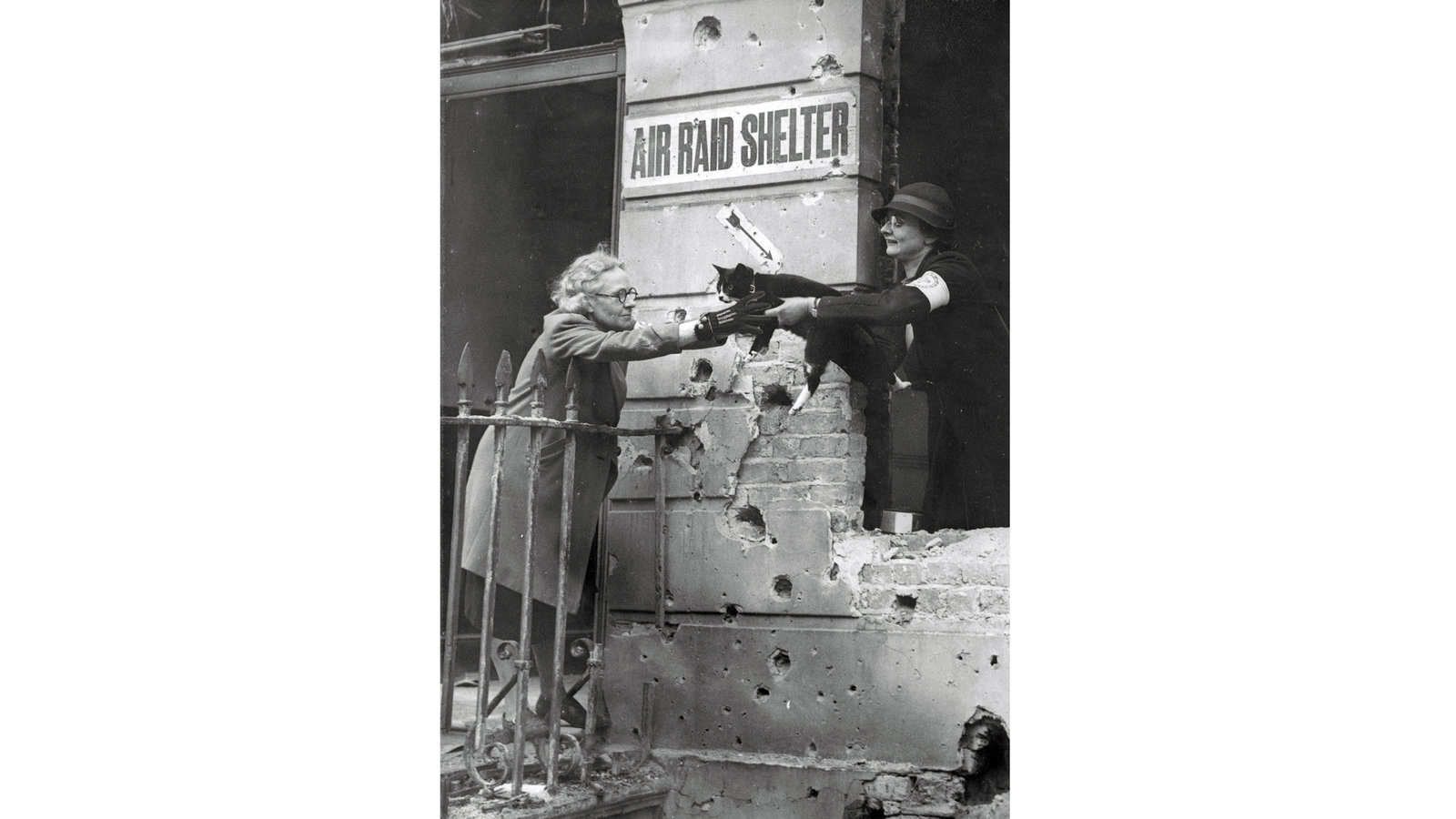

When the Blitz started in the autumn of 1940, surviving pets faced a dire situation as bombing intensified.

A vet from London described streets filled with abandoned cats left to roam the darkened city. In response, municipal teams launched mass euthanasia efforts, sometimes killing up to 100 animals at a time using methods like chloroform, cyanide, or electric shocks.

While some people panicked, others sought to calm the public. In the Daily Mirror, Susan Day urged people not to make hasty decisions: “Putting your pets to sleep is a very tragic decision. Do not take it before it is absolutely necessary.”

In fact, some pet owners found ways to keep their animals despite the chaos. Pauline Caton, who was just five years old and living in Dagenham, remembers standing in line with her family at a local market to buy horse meat for their cat.

Despite limited resources, Battersea Dogs & Cats Home managed to care for 145,000 dogs during the war, with only four staff members.

In the midst of this turmoil, some people fought to save the animals. The Duchess of Hamilton, a wealthy cat lover, rushed to London and made an urgent appeal on the BBC: “Homes in the country urgently required for those dogs and cats which must otherwise be left behind to starve to death or be shot.”

“Being a duchess she had a bit of money and established an animal sanctuary,” says historian Kean. The Duchess even set up a sanctuary in a heated aerodrome in Ferne, rescuing hundreds of animals from London’s East End. Initially, she housed them at her home in St John’s Wood, despite complaints from neighbors about the noise.