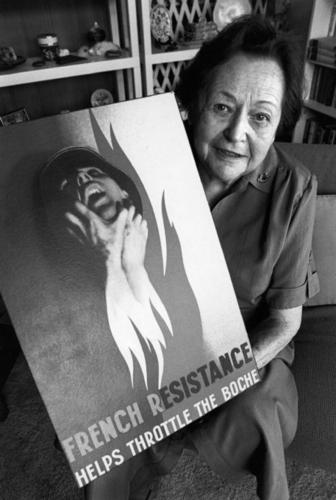

Nancy Wake, famously known as the White Mouse, earned her nickname for skillfully evading the Gestapo in occupied France, even with a 5 million franc bounty on her head. The Nazis dubbed her this for her uncanny ability to outsmart them.

As one of Churchill’s most decorated special agents, Wake symbolized courage and ingenuity.

With her stylish hair and bold red lipstick, Wake was the picture of glamor. However, when she was parachuted into occupied France, she became a formidable force against the enemy.

In an interview at 89, Wake’s fierce spirit was undiminished.

When asked if she had ever been afraid, she responded with characteristic bravado, “Somebody once asked me: ‘Have you ever been afraid?’ Hah! I’ve never been afraid in my life,” she said.

Nancy Wake committed to fighting Nazism

Nancy Wake had a difficult childhood growing up in Sydney. Raised by a rigidly strict mother and an absent father, who abandoned the family to pursue filmmaking in New Zealand, Nancy faced upheaval and financial hardship.

Her rebellious nature and fiery temper seemed to stem from this tumultuous family dynamic.

At just 16 years old, Nancy fled from home and found work as a nurse. Inheriting £200 from an aunt, she embarked on a journey to New York City, then London, where she honed her skills as a journalist.

Then, she visited Vienna and witnessed the horrors of the Nazi regime firsthand. She saw Jewish people being brutally attacked by Nazi gangs in the streets. She vowed to do anything she could to combat the spread of Nazism.

She recalled, “The stormtroopers had tied the Jewish people up to massive wheels. They were rolling the wheels along, and the stormtroopers were whipping the Jews. I stood there and thought, ‘I don’t know what I’ll do about it, but if I can do anything one day, I’ll do it.’ And I always had that picture in my mind, all through the war.”

“I hate wars and violence but if they come then I don’t see why we women should just wave our men a proud goodbye and then knit them balaclavas,” she said.

In 1939, when German troops invaded Poland, Britain and France responded by declaring war on Germany.

During this tumultuous time, Wake was in England, but she quickly returned to France. There, she married Henri Fiocca, a dashing and wealthy French industrialist.

She drew herself into the fight

Despite her wealth and ability to avoid the war’s hardships, Nancy Wake chose a different path.

In 1940, she joined the fledgling resistance movement, transporting messages and food to underground groups in Southern France. Additionally, she purchased an ambulance to assist refugees escaping the German advance.

As the beautiful wife of a wealthy businessman, Nancy had a unique ability to travel freely, a privilege few could imagine.

Reflecting on her work, she noted, “It was much easier for us, you know, to travel all over France. A woman could get out of a lot of trouble that a man could not.”

She secured false papers to live and work in the Vichy zone of occupied France. Deeply involved in the Resistance, she helped over a thousand escaped prisoners of war and downed Allied fliers flee France.

Although she was judged to be unruly, her high spirits and physical daring were seen as boosting morale.

After the fall of France in 1940, she joined Captain Ian Garrow’s escape network, which later became known as the Pat O’Leary Line.

The Gestapo, impressed by her ability to evade capture, dubbed her the “White Mouse” and placed her at the top of their wanted list, offering a five million franc reward for her capture.

Her missions were dangerous; the Gestapo tapped her phone and intercepted her mail, constantly threatening her life.

Eventually, she decided to flee France, but her husband, Henri Fiocca, stayed behind. Tragically, he was captured, tortured, and executed by the Gestapo.

With the net closing in, Wake escaped to England and joined the British Special Operations Executive (SOE)’s French Section. This unit of 470 men and women was trained to support local resistance groups in territories occupied by the Germans.

In 1944, Wake parachuted back into France to assist with D-Day preparations. She commanded 7,000 Maquis troops, conducting guerrilla warfare to disrupt Nazi operations. Her comrade, Henri Tardivat, later said:

“She is the most feminine woman I know, until the fighting starts. Then she is like five men.”

When the destruction of radio codes threatened their supply drops, she undertook a grueling bike ride, covering around 500 km in 72 hours and crossing multiple German checkpoints to find an operator who could radio Britain for new codes.

She took on this dangerous mission because a woman was considered more likely to succeed.

Wake becomes an inspiration

The war brought personal tragedy for Nancy Wake. When she returned to her home in Marseille after the liberation, she found out that her husband, Henri Fiocca, had been tortured and killed by the Gestapo because he refused to betray her.

Nancy’s hatred for the enemy was profound. She once stated, “In my opinion, the only good German was a dead German, and the deader, the better. I killed a lot of Germans, and I am only sorry I didn’t kill more.”

It’s no surprise she was at the top of the Gestapo’s most-wanted list. Nancy Wake passed away at 98, after being hospitalized with a chest infection at Kingston Hospital.

Peter FitzSimons, author of “Nancy Wake: A Biography of Our Greatest War Heroine,” published in 2001, said she was “10 times the man I would ever be.”

Her remarkable life also inspired Sebastian Faulks’ 1999 novel, “Charlotte Gray,” which was later adapted into a film starring Cate Blanchett as Wake.