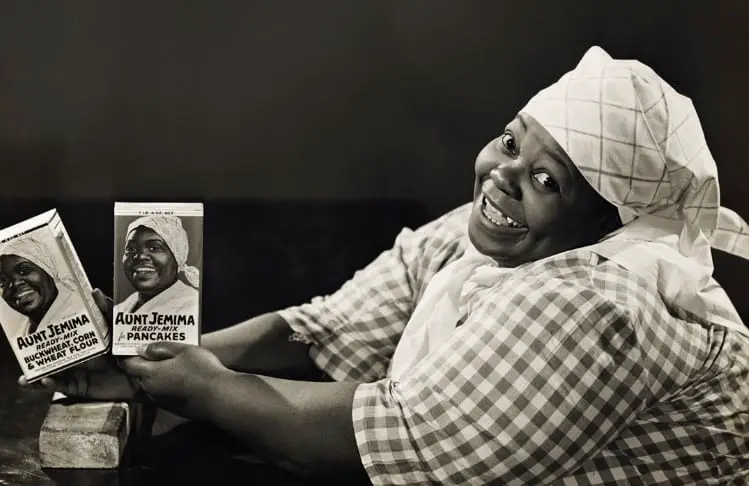

You probably have never heard her name, but Nancy Green has likely made her way into your kitchen before. She’s the one behind the Aunt Jemima recipe, which helped popularize American pancakes.

Nancy was among the first African-American models hired to promote a brand. Although the Aunt Jemima recipe wasn’t originally hers, she became the face of the brand, essentially becoming the first living trademark in advertising.

Sherry Williams, president of the Bronzeville Historical Society in Chicago, told ABC News, “Her face on the box, that image on the box, was probably the one way that households were integrated.”

The Pre-Fame Life Of Nancy Hayes Born Into Slavery

Nancy Hayes (or Hughes) was born in slavery in the Antebellum South on March 4, 1834. She came into the world at a farm on Somerset Creek, about six miles outside Mount Sterling in Montgomery County, Kentucky.

Nancy Green wore many hats in her lifetime. She was a servant, nurse, nanny, housekeeper, and cook for Charles Morehead Walker and his wife Amanda.

She looked after the family’s children and kept their home running smoothly. Even as time passed, she continued caring for the next generation, serving as both a nanny and a cook.

The Walker family’s legacy lived on through their sons, including Chicago Circuit Judge Charles M. Walker Jr., and Dr. Samuel J. Walker.

By the end of the American Civil War, Nancy lived in a simple wooden shack behind a grand home on Main Street in Covington.

When the Walkers relocated from Kentucky to Chicago in the early 1870s, Nancy went with them, even before Dr. Samuel Walker’s youngest child was born in 1872.

Her Path To Be A Renowned Figure

Judge Walker recommended Nancy Green for a job at the R.T. Davis Milling Company in St. Joseph, Missouri. They wanted someone to represent their product, “Aunt Jemima,” which was named after a song from a minstrel show. They were specifically looking for a character that fit the Mammy stereotype to promote their product.

At the age of 59, Nancy Green made her first appearance as Aunt Jemima at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago. She worked beside a huge flour barrel that was 24 feet tall.

Her role was to demonstrate pancake cooking, sing songs, and share stories about the Old South. These stories portrayed a romanticized version of the past, claiming that it was a happy place for both black and white people.

After the Expo, Green was offered a lifetime contract to become Aunt Jemima and promote pancake mix. She traveled across the country and earned a great sum of money.

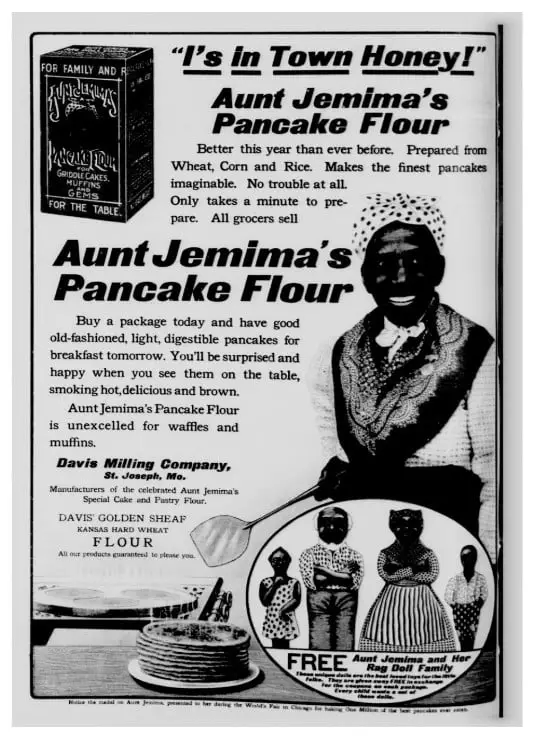

The company launched a huge promotional campaign, with Green making appearances at various events like fairs, festivals, and grocery stores. Billboards announced her arrival with the catchy phrase, “I’s in town, honey.”

Despite the supposed lifetime contract, she only stayed in the role for around 20 years. She refused to cross the ocean for the 1900 Paris exhibition.

Another woman, Agnes Moodey, described as “a negress of 60 years,” then took on the role and was presented as the original Aunt Jemima.

The Image Of Aunt Jemima “Erased”

As we know that the Aunt Jemima brand has a long history that dates back over 130 years. It was initially created with a portrayal of a Black woman named Aunt Jemima, who was dressed as a minstrel character.

This depiction, with its exaggerated features and stereotypical attire, has faced significant backlash and controversy over the years.

In recent times, there has been a growing recognition of the negative impact and perpetuation of racial stereotypes associated with Aunt Jemima’s image.

Many people have voiced concerns that the brand’s portrayal of Aunt Jemima reinforces outdated and harmful stereotypes, particularly the “mammy” stereotype linked to the era of slavery.

In response to these criticisms and a call for change, Quaker, a subsidiary of PepsiCo, decided to modify the character’s image by removing the “mammy” kerchief from Aunt Jemima’s head, which was seen as a symbol of the racist stereotype.

“We recognize Aunt Jemima’s origins are based on a racial stereotype,” Kristin Kroepfl, vice president and chief marketing officer of Quaker Foods North America, said in a news release.

“As we work to make progress toward racial equality through several initiatives, we also must take a hard look at our portfolio of brands and ensure they reflect our values and meet our consumers’ expectations.”

Nancy Green’s Legacy For Society And Death

Nancy Green was an active member of the Chicago Olivet Baptist Church. The church grew a lot during her time there and became the biggest African-American church in the U.S., with over 9,000 members back then. She spoke up against poverty and fought for equal rights for people in Chicago.

Sadly, Nancy Green passed away on August 30, 1923, at 89 years old in Chicago. She was hit by a car driven by Dr. H. S. Seymour, a pharmacist, had collided with a laundry truck and ended up on the sidewalk where she was standing.

She was buried in a poor person’s grave near a wall in the northeast part of Oak Woods Cemetery in Chicago.

For many years, nobody knew where Nancy Green was buried until 2015. Sherry Williams, who started the Bronzeville Historical Society, spent 15 years searching for her grave.

She asked Quaker Oats if they would help make a monument for Nancy Green’s grave, but they said no, “Their corporate response was that Nancy Green and Aunt Jemima aren’t the same – that Aunt Jemima is a fictitious character.” Finally, on September 5, 2020, a headstone was put on Nancy Green’s grave.