Cooking legend Julia Child introduced French cuisine to American cooks in 1963 with GBH’s pioneering television series, The French Chef.

Since her first cooking program aired, she has inspired millions of amateur cooks and many professional chefs with her well-honed skills, easy kitchen spirit, and passion for learning.

Beyond her culinary achievements, Child’s fascinating life included wartime service with the OSS and a commitment to food education, making her a beloved figure in both the culinary world and popular culture.

Explore the world of Julia Child as she herself said, “Bon appétit!”

Her early years and education

Julia Child, born Julia Carolyn McWilliams on August 15, 1912, in Pasadena, California, was the eldest of three siblings.

Her father, John McWilliams Jr., was a Princeton graduate and land manager, and her mother, Julia Carolyn (“Caro”) Weston, was a paper-company heiress and the daughter of Massachusetts lieutenant governor Byron Curtis Weston.

She attended Polytechnic and Westridge Schools in Pasadena, then the Katherine Branson School in Ross, California, for high school.

Julia enjoyed sports like tennis, golf, and basketball. She continued playing sports at Smith College, where she graduated in 1934 with a major in history, aspiring to become a novelist or magazine writer.

Although Julia grew up in a family with a cook, she never learned to cook from them. She only began learning about cooking after meeting her future husband, Paul, who came from a family that loved food.

Her intriguing spy days

When the United States entered World War II, Julia wanted to serve her country. She was too tall to join the military at 6’2″, so she volunteered for the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), the precursor to the CIA.

The OSS praised her in their interview notes, describing her as making a “good impression, pleasant, alert, capable, very tall.”

Julia worked directly for the OSS’s leader, General William J. Donovan, in its headquarters in Washington. Julia was one of 4,500 women who served in the OSS.

Like most women at the OSS then, she worked as a research assistant in the Secret Intelligence branch. Her job was typing hundreds of names on small white note cards, a system used to keep track of officers before the advent of computers.

Despite the boring work, her skills and experience stood out. She steadily moved up the ranks, gaining more responsibilities in different departments.

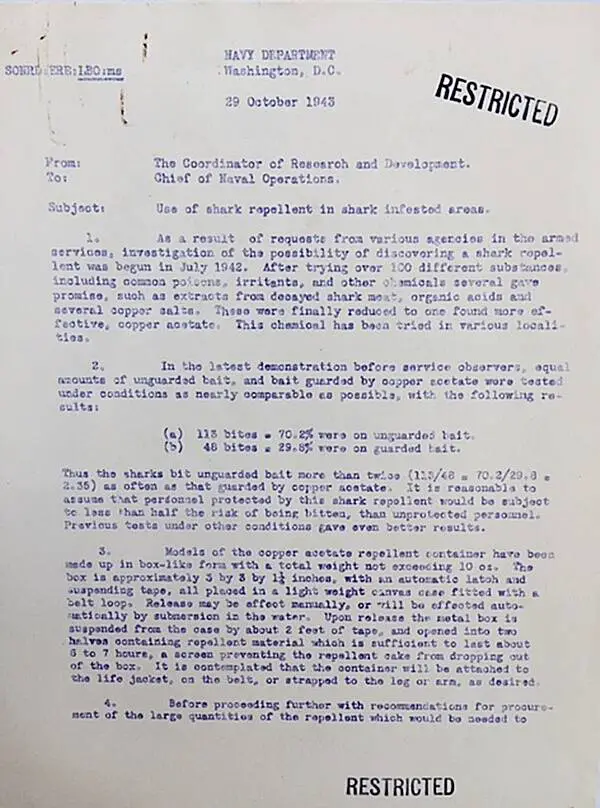

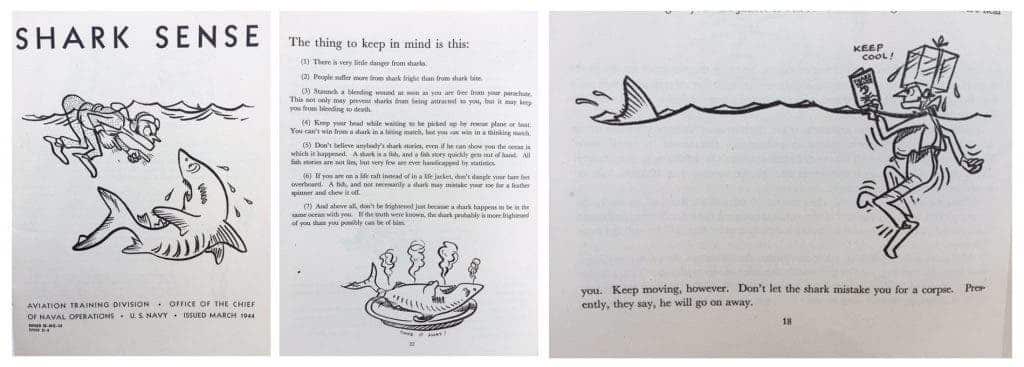

Julia then worked with the OSS Emergency Sea Rescue Equipment Section, developing shark repellent to protect explosives targeting German U-boats. Curious sharks would sometimes trigger the underwater explosives, so the repellent was crucial.

When Child was asked to solve the problem of curious sharks, “Child’s solution was to experiment with cooking various concoctions as a shark repellent,” which were sprinkled in the water near the explosives and successfully repelled sharks.

This experimental shark repellent, still in use today, “marked Child’s first foray into the world of cooking.” She once shared: “My first big recipe was shark repellant that I mixed in a bathtub for the Navy, for the men who might get caught in the water.”

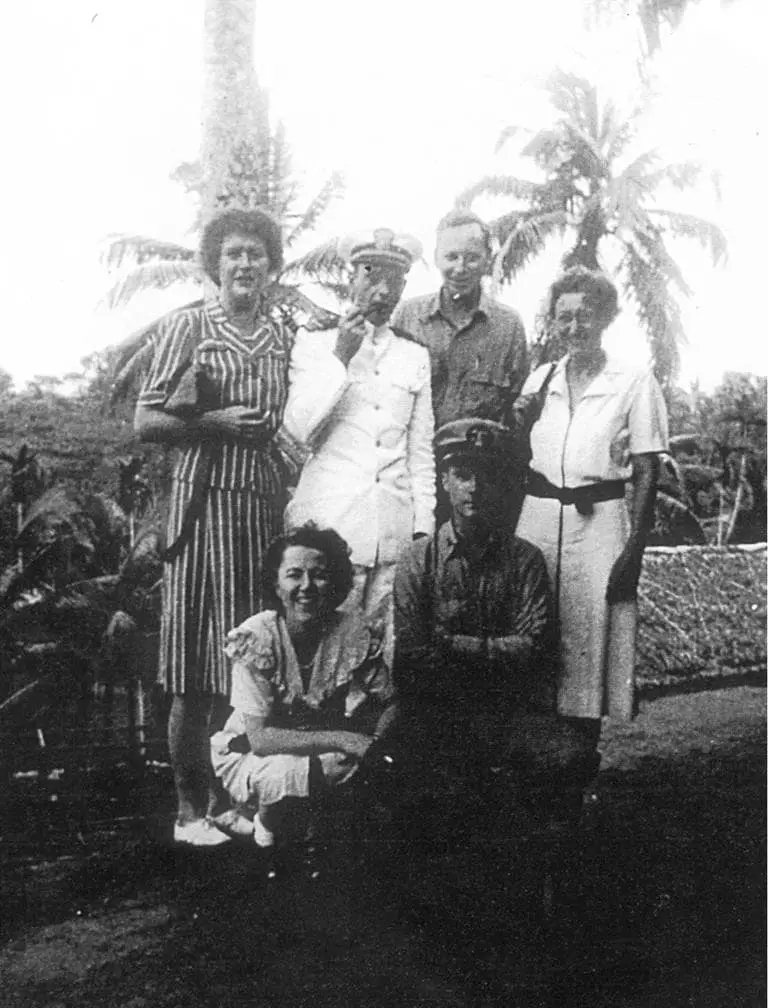

In her next role, Child traveled further, working in Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) and then in China from 1944 to 1945. Also there, she received the Emblem of Meritorious Civilian Service serving as Chief of the OSS Registry.

In a letter from her posting, she wrote, “There are movies and dances twice a week at the American officers’ club, walks in the moonlight. On Sundays, there are picnics, golf, tennis, swimming, or a weekend down in Colombo.”

As Chief, she had top security clearance and handled every incoming and outgoing message, dealing with highly classified information about the invasion of the Malay Peninsula. Despite the danger, Julia found the work fascinating.

Air Force intelligence officer Byron Martin admired her dedication and intellect and described her as “a person of unquestioned loyalty, of rock-solid integrity, of unblemished lifestyle, and of keen intelligence.”

When the war ended, Child left the OSS for good. She took with her two important souvenirs: the French she had learned from private lessons in Washington D.C., and her husband, Paul Cushing Child, who would later introduce her to French cuisine.

Her remarkable turning to a cooking career

In 1948, when Paul was reassigned to the U.S. Information Service at the American Embassy in Paris, the newlyweds moved to France.

Julia Child often recalled her first meal at La Couronne in Rouen as a culinary revelation, describing the meal of oysters, sole meunière, and fine wine as “an opening up of the soul and spirit for me.”

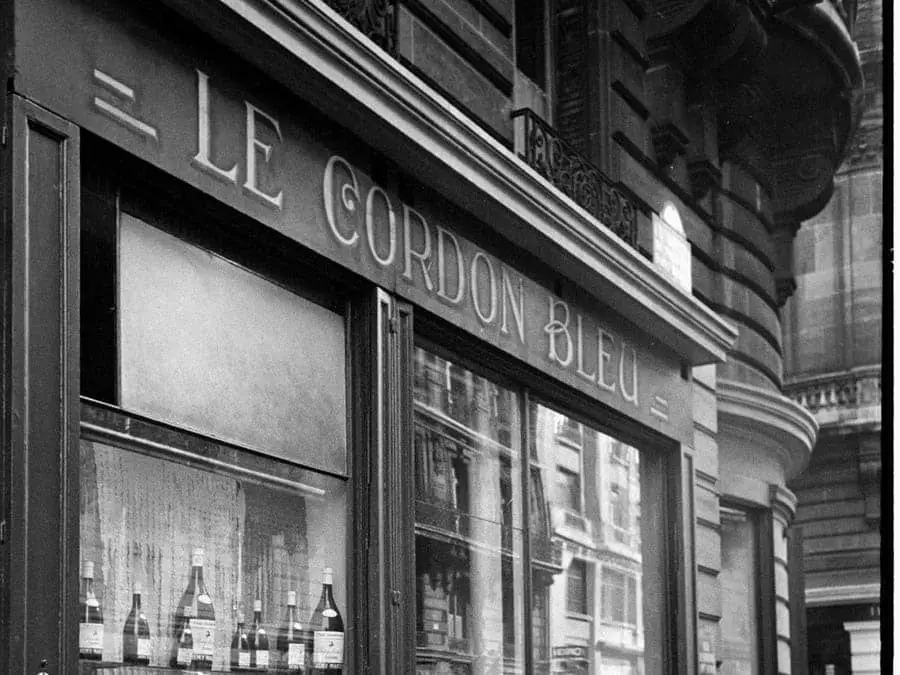

In 1951, she graduated from the renowned Cordon Bleu cooking school in Paris and later studied privately with master chefs, including Max Bugnard.

She joined the women’s cooking club Le Cercle des Gourmettes and luckily met Simone Beck, who was writing a French cookbook for Americans with Louisette Bertholle. Beck invited Julia to collaborate to make the book more appealing to Americans.

That same year, Child, Beck, and Bertholle began teaching American women to cook in Julia’s Paris kitchen, naming their informal school L’école des trois gourmandes (The School of the Three Food Lovers).

Over the next decade, as the Childs moved around Europe and eventually settled in Cambridge, Massachusetts, the three women researched and tested recipes. Julia translated the French recipes into detailed, interesting, and practical English versions.

Her outstanding achievements

Cookbooks and Recipes

Julia Child aimed to adapt sophisticated French cuisine for mainstream Americans.

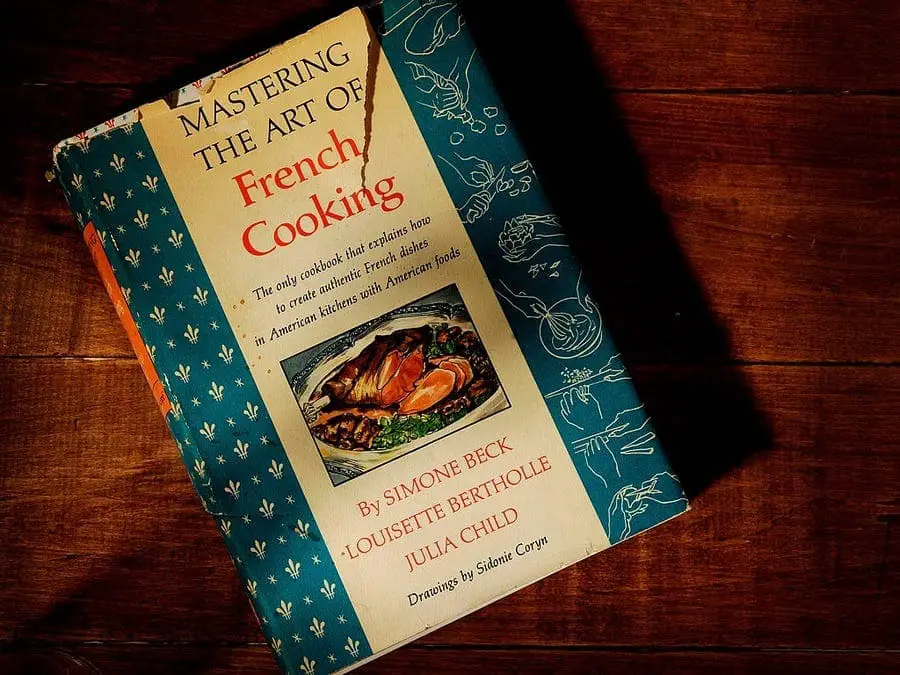

She and her colleagues, Simone Beck and Louisette Bertholle, collaborated on the two-volume cookbook, Mastering the Art of French Cooking. Released in September 1961, it was groundbreaking and remained the bestselling cookbook for five years.

Child authored several bestsellers, including In Julia’s Kitchen with Master Chefs (1995), Baking with Julia (1996), Julia’s Delicious Little Dinners (1998), and Julia’s Casual Dinners (1999), all accompanied by successful TV specials.

Her autobiography, My Life in France, was published posthumously in 2006 with the help of her great-nephew, Alex Prud’homme.

Fans learned recipes for her signature dishes, such as beef bourguignon, French onion soup, and coq au vin, through her many cookbooks. Initially, Houghton Mifflin rejected the manuscript of Mastering the Art of French Cooking for being too encyclopedic.

However, when Alfred A. Knopf published it in 1961, the 726-page book became a bestseller, acclaimed for its detailed illustrations and making fine cuisine accessible. It remains in print and is considered a seminal culinary work.

Following its success, Child wrote magazine articles and a column for The Boston Globe. She published nearly twenty titles, many related to her television shows.

Her last book, the autobiographical My Life in France, recounts her life with her husband, Paul Cushing Child, in postwar France.

TV shows

In 1962, Julia Child promoted her first cookbook on a local public television station near her home in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Her direct manner and humor while preparing an omelet resonated with viewers, leading to an invitation to host her own cooking series.

Starting at $50 per show, The French Chef debuted on WGBH in 1963 and quickly became a hit, transforming how Americans approached food and catapulting Child to local celebrity status. The show’s popularity led to syndication on 96 stations across the country.

Though not the first television cook, Child was the most widely seen. She captivated audiences with her cheery enthusiasm, distinctive warbly voice, and genuine, unpretentious manner.

In 1972, The French Chef became the first TV program to be captioned for the deaf, using the early technology of open-captioning.

Julia Child continued her television career with series like Julia Child and Company (1978), Julia Child and More Company (1980), and Dinner at Julia’s (1983).

Concurrently, she made frequent appearances on the ABC morning show Good Morning America, maintaining her influence on American culinary culture.

Awards and honors

On November 19, 2000, Julia Child was awarded the Knight of France’s Legion of Honor. She became a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in the same year. In 2003, she received the U.S.

Presidential Medal of Freedom and was granted honorary doctorates from Harvard University, Johnson & Wales University (1995), Smith College (her alma mater), Brown University (2000), and several other universities.

In 2007, Child was inducted into the National Women’s Hall of Fame.

During her television career, Julia Child received the George Foster Peabody Award in 1965 and an Emmy Award in 1966. In 1993, she became the first woman inducted into the Culinary Institute Hall of Fame.

Her contributions to culinary arts were further recognized in August 2002 when the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History unveiled an exhibit featuring the kitchen where she filmed three of her popular cooking shows.

Her immortalized legacy

After her television success, Julia Child continued to influence cooking in America. In 1981, she co-founded the American Institute of Wine & Food, aiming to promote a better understanding of food and drink.

Even in her later years, Child remained active in the culinary world. She became increasingly concerned about children’s food education.

Julia Child faced criticism for using ingredients like butter and cream. She warned against a “fanatical fear of food” and believed overemphasis on nutrition ruined the joy of eating.

In a 1990 interview, she said, “If fear of food continues, it will be the death of gastronomy in the United States. We should enjoy food and have fun. It is one of the simplest and nicest pleasures in life.”

In 2001, Julia Child moved to a retirement community and donated her house and office to Smith College. She donated her kitchen, designed with high counters to suit her height and used as the set for three of her TV series, to the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History.

Her copper pots and pans exhibited at Copia in Napa, California, were reunited with her kitchen in Washington, D.C., in 2009.

Julia Child died in August 2004 of kidney failure at her assisted-living home in Montecito, California, just two days before her 92nd birthday.

She remained active and enthusiastic about her work until the end, famously stating, “In this line of work … you keep right on till you’re through. Retired people are boring.”

Child’s legacy endures through her cookbooks and syndicated cooking shows. On August 15, 2012, what would have been her 100th birthday, restaurants across the nation celebrated Julia Child Restaurant Week featuring her recipes.

In 2009, the film Julie & Julia, directed by Nora Ephron and starring Meryl Streep and Amy Adams, depicted aspects of Child’s life and her influence on aspiring cook Julie Powell.

Meryl Streep’s portrayal of Child earned her a Golden Globe Award for Best Actress and an Academy Award nomination.

Julie Powell described Child’s television presence as “magical” and pioneering.

She noted, “Her voice and her attitude and her playfulness … it’s just magical. And you can’t fake that; you can’t take classes to learn how to be wonderful. She just wanted to entertain and educate people at the same time. Our food culture is the better for it. Our stomachs are the better for it.”