On February 29, 1940, the epic film “Gone with the Wind” made history at the Academy Awards, sweeping eight Oscars across major categories.

Set against the backdrop of the Civil War, the film captivated audiences and critics alike, earning accolades for Best Picture, Director, Screenplay, and more. However, the most groundbreaking moment of the night belonged to Hattie McDaniel, the first Black person to win an Oscar.

Her victory marked a significant milestone in the entertainment industry, breaking barriers and paving the way for future generations of Black actors and actresses.

Hattie McDaniel believed she was opening doors for people of color in the entertainment industry, but she faced criticism for accepting roles that reinforced racial stereotypes.

From humble beginnings to the first film role

Born on June 10, 1895, in Wichita, Kansas, Hattie McDaniel was the 13th child of former slaves. Her family moved to Colorado when she was six, and it was there that she discovered her love for performing.

“I knew that I could sing and dance…my mother would give me a nickel sometimes to stop,” McDaniel humorously recalled. At 15, she dropped out of high school to pursue acting, eventually joining her brother in a traveling carnival, according to the Colorado Virtual Library.

McDaniel’s career began to gain momentum when she produced an all-women’s minstrel show with her sister in 1914. Later, she became the lead singer for George Morrison’s Melody Hounds, a popular jazz orchestra.

This success led her to Hollywood, where she landed her first film role in 1932.

Making history with “Gone with the Wind”

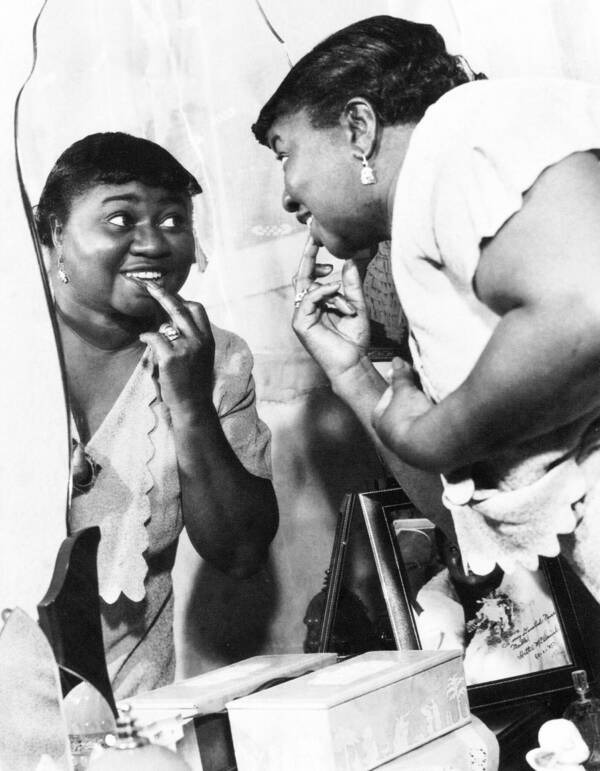

Her most iconic role came in 1939 as Mammy in Gone with the Wind. The film’s success and her outstanding performance earned McDaniel an Academy Award, making her the first Black actor to receive the honor.

On the night of the ceremony, McDaniel wore a stunning turquoise gown adorned with rhinestones and white gardenias in her hair.

As she stepped onto the stage to accept her Oscar, the room filled with emotion and pride, and thunderous applause echoed through the venue.

In her acceptance speech, she said, “I shall always hold it as a beacon for anything I may be able to do in the future. I sincerely hope that I shall always be a credit to my race and the motion picture industry.”

A win overshadowed by segregation and criticism

McDaniel was treated as a second-class citizen due to her race, even when she had an Oscar in hand.

The Oscar ceremony was held at the Coconut Grove nightclub, which was part of the whites-only Ambassador Hotel. Hattie McDaniel was only allowed entry after producer David O. Selznick intervened on her behalf.

When she arrived, McDaniel was escorted to “a small table set against a far wall,” where she spent the evening with her Black escort, F.P. Yober, and her white agent, William Meiklejohn.

She was not allowed to sit with her fellow cast members, who were all white. It would be two decades before another Black actor, Sidney Poitier, would win an Oscar in 1963 for Best Actor.

McDaniel continued to face persistent criticism from African American activists for the roles she accepted. Out of her 300 film credits, around 75 percent were caricatures of Black women.

Even after winning her Oscar, she continued to be typecast in similar, demeaning roles. The studio even forced her to do a post-Oscar tour in her Mammy costume, a theatrical promotion designed to capitalize on her success.

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) disavowed McDaniel for starring in films that portrayed racist stereotypes of Black people.

In 1947, McDaniel defended herself in an op-ed in “The Hollywood Reporter,” stating,

“Several times I have persuaded the directors to omit dialect from modern pictures. They readily agreed to the suggestion. I have been told that I have kept alive the stereotype of the Negro servant in the minds of theatre-goers. I believe my critics think the public more naïve than it actually is.”

She added: “I’d rather play a maid than be a maid.” At the time, refusing such roles often meant losing work for actors of color.

A lasting legacy of generosity and perseverance

Despite the backlash, McDaniel believed in the impact of her work. She maintained an open-door policy for fellow African American creatives at her Los Angeles home.

As chairman of the Black division of the Hollywood Victory Committee, she also organized shows for African American troops during World War II and generously donated to the NAACP despite their criticisms.

In her later years, McDaniel became the first Black actress to star in a successful radio show, “Beulah.” Sadly, after her death in 1952, her Oscar plaque went missing, and her final wish to be buried in the Hollywood Cemetery was denied due to her race.

Despite these challenges, Hattie McDaniel’s legacy endures. Her Oscar win paved the way for future Black actresses like Whoopi Goldberg, Octavia Spencer, and Viola Davis.

As McDaniel once said, “I sincerely hope that I shall always be a credit to my race and the motion picture industry.” Her trailblazing career ensured that she would be remembered as both.