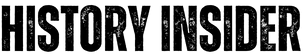

Margaret Bourke-White was a woman of firsts in the photography field. She became the first staff photographer for Fortune, the first Western photographer allowed inside the Soviet Union, and Life magazine’s first female photographer.

During World War II, she broke barriers again as the first female war correspondent to work in combat zones. Her fearless approach and eye for detail captured some of the most iconic images of the 20th century, making her a true pioneer in photojournalism.

Her Family Background Shaped Her Personality

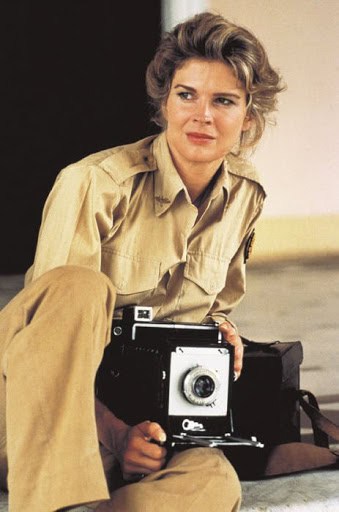

Margaret Bourke-White, originally named Margaret or Maggie White, is best known by the last name she made famous. Her father, Joseph White, was an inventor and engineer, while her mother, Minnie, was forward-thinking.

Joseph shared his passions with his kids, and when Margaret was eight, she joined him to see his printing presses being made. The sight of molten iron had a lasting impact on her, sparking a lifelong fascination with industrial photography.

In the fall of 1921, Margaret Bourke-White started college at Columbia University, where she took a photography class with Clarence H. White. She loved it, and after her father’s passing in 1922, her mother bought her a second hand camera.

After attending Rutgers University for summer school, she transferred to the University of Michigan to study herpetology, where she married Everett Chapman in 1924. They later transferred to Purdue and then Western Reserve. When the marriage ended, she moved to Cornell in 1926 for her senior year, drawn by the campus waterfalls.

How her early professional life was

While at Cornell, Margaret Bourke-White earned money by selling photos of the campus. After receiving praise from architects for her work, she went to New York to get feedback on her portfolio and was told she could easily find jobs with architectural firms. After graduating, she changed her name to Margaret Bourke-White, blending her maiden name with her mother’s.

She moved to Cleveland and, despite resistance, gained access to the city’s steel mills. Operating out of a small studio, she produced stunning images of the steel-making process, which impressed the head of Otis Steel. This led to the publication of her portfolio, The Otis Steel Company, in 1929.

At Fortune, she became known for her unique industrial photography

Henry Luce, the publisher of Fortune magazine, noticed Bourke-White’s striking photographs of Otis Steel Company and wanted to feature industrial beauty in his new publication. He sent her a telegram saying, “Have just seen steel photographs. Come to New York.”

Bourke-White ignored it at first but later decided to take a free trip. She liked what she heard and joined Fortune in 1929 at the age of 25. Soon after, she was sent to Chicago to photograph the Swift and Company meatpacking plant, where her work on “Hogs” helped popularize the photographic essay.

In 1930, Fortune sent her to Germany to capture the country’s rising industries. Her next big challenge was gaining access to Russia, a place closed off to foreign photographers. Through her connections with Cleveland industrialists and her relentless efforts, Bourke-White managed to secure entry, becoming the first Western photographer allowed into the Soviet Union.

Between 1930 and 1933, Margaret Bourke-White made three trips to the Soviet Union, capturing images of industry and daily life. Her work was published in Soviet magazines, Fortune, The New York Times Sunday Magazine, and her book Eyes on Russia.

In 1932, she photographed Soviet medical institutions for a report called Red Medicine: Socialized Health in Soviet Russia, featuring eight of her photos. She even dedicated the rights of these images to the public.

Her work gained respect in both popular and academic circles, leading to museum exhibits and lectures. Bourke-White also received endorsement offers, including one from Maxwell House Coffee, which helped fund her career.

At LIFE, she captured many of history’s most famous moments

In 1936, Henry Luce hired Margaret Bourke-White as a full-time photographer for his new magazine, LIFE, making her the first female staff member. She also helped promote LIFE through her work.

Her famous photograph of Fort Peck Dam in Montana appeared on the magazine’s first cover on November 23, 1936. It sold out quickly, and in just four months, circulation soared from 380,000 to over one million copies a week.

The image of the dam became a symbol of economic recovery during the Great Depression and was later chosen by the United States Postal Service to represent the 1930s in its Celebrate the Century stamp series.

Bourke-White specialized initially in photographing industry: the men, machines, materials, and buildings that had fascinated her in childhood. But she was changing. Social issues became increasingly important to her, and she often requested assignments to areas of dynamic social change, where strife satisfied her appetite for living dangerously.

When Margaret Bourke-White began working for Life, she collaborated with author Erskine Caldwell on a book that captured the effects of the Great Depression on Southern life. Traveling through Georgia, Mississippi, Alabama, South Carolina, Arkansas, and Tennessee, Caldwell wrote about the struggles of the poorest citizens while Bourke-White took photographs of their living conditions.

Released in November 1937, You Have Seen Their Faces received critical acclaim and became popular, though it faced criticism for reinforcing stereotypes and misrepresenting the voices of those featured. Unlike Walker Evans and James Agee’s Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, which struggled to gain traction, Bourke-White’s book quickly found an audience, though Agee and Evans were outraged by it.

In Czechoslovakia and Hungary

In 1938, Life sent Bourke-White and Caldwell to Czechoslovakia and Hungary to document the rise of Hitler and Nazism. Disturbed by what they witnessed, they extended their trip to capture the violence and anti-Semitism in the region.

Their experiences were published in 1946 as Dear Fatherland, Rest Quietly: A Report On The Collapse Of Hitler’s Thousand Years. They also spent about six months abroad on various assignments, gathering material for the book later released as North of the Danube.

In the Soviet Union

Life sent Margaret Bourke-White to England to capture the country’s war preparations, and she later traveled through Romania, Turkey, and the Middle East.

In the summer of 1941, she and her husband, Caldwell, went to the Soviet Union, where Bourke-White became the only Western photographer in Moscow during the German attack on the city. As bombs fell, she and Caldwell took shelter while Bourke-White captured stunning photos of the attack, including one of the Kremlin lit up by explosions.

When she returned to the U.S. shortly after it entered the war, Bourke-White made history as the first female war correspondent accredited by the military. The agreement between Life magazine and the Pentagon allowed them and the Air Force to use any photos she took.

In England and the North Africa

Bourke-White spent months at an Air Force base in England, taking photos of military maneuvers. She also traveled to London to capture images of King George, Winston Churchill, and Ethiopian Emperor Haile Selassie.

When she learned about secret plans to invade North Africa, she asked to cover the Allied invasion. Instead of flying there, which was for high-ranking officers, she went by boat, which came under torpedo attack.

She escaped on a flooded lifeboat and took pictures of the dangerous situation with the one camera she saved. She was also allowed to join and photograph a bombing mission, a privilege no other woman had before.

In Italy

In 1943, Bourke-White documented the war in Italy from the ground. Despite surviving torpedo and artillery attacks, she said she had never felt as scared as when she was crawling on the battlefield with mortar shells and enemy fire all around her. She left Italy in 1945, traveling with General Patton as his troops advanced through Germany.

In Germany

In Germany, Bourke-White barely recognized the prosperous country she had photographed just a few years earlier — cities were destroyed and the people were defeated.

This time, she photographed some of the most horrible scenes of the war: Nazi officials and their families dead by suicide, the liberation of the Weimar concentration camp, and a small Nazi work camp where the Jewish prisoners had been set on fire.

She distanced herself from the horrors by concentrating on the act of making photographs; it was only when she developed her prints that she acknowledged the horror she had observed. Bourke-White’s father was Jewish, something she kept secret from all but three or four friends.

What her later life looked like

Margaret Bourke-White continued working for LIFE even after being diagnosed with Parkinson’s in 1954. Despite physical therapy, by 1957, she could no longer pursue photography professionally. For nearly 20 years, she fought the disease, undergoing intense rehabilitation and two major brain surgeries in an effort to slow its progress.

While unable to photograph, she focused on writing her autobiography, Portrait of Myself, which she completed between 1955 and 1963. Bourke-White passed away on August 27, 1971, after a long battle with Parkinson’s disease.