The longing for a child is profound and universal. For many couples, the journey to parenthood is filled with hope, excitement, and sometimes heartache.

In the face of infertility, this journey often involves exploring every available option to make their dream a reality. This pursuit of parenthood led to one of the most remarkable medical breakthroughs of the 20th century: in vitro fertilization (IVF).

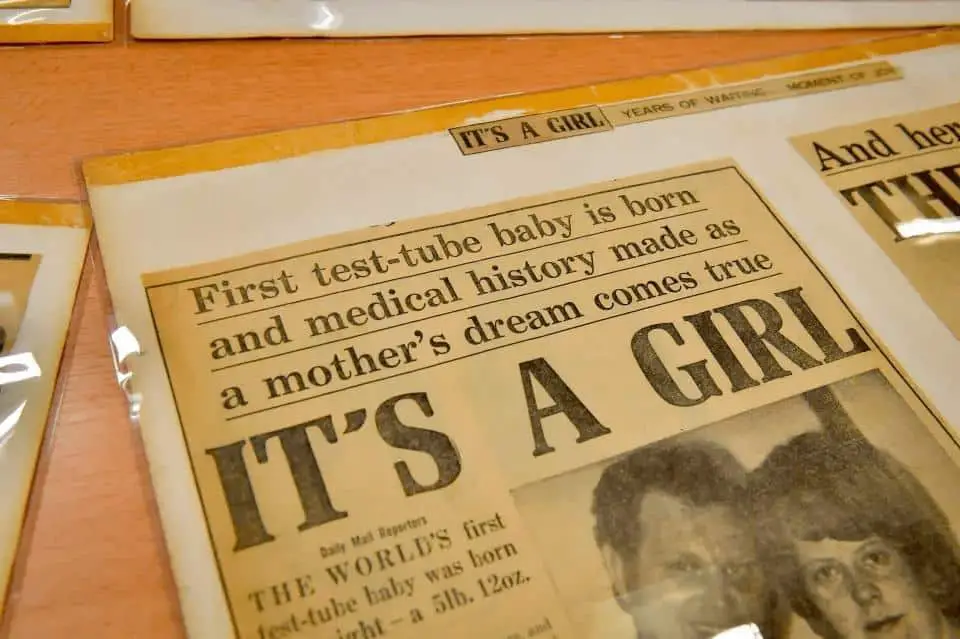

On July 25, 1978, there was a huge media event: Louise Brown became the world’s first “test-tube baby.” She captured public attention and generated headlines worldwide. Let’s uncover the heartwarming story behind her historic birth.

The struggle for parenthood of Lesley and John Brown

Lesley and John Brown were from Bristol, where John worked as a driver for British Rail. John had two daughters from a previous marriage: Beverly was raised by John’s stepmother’s daughter, and Sharon had lived with John and Lesley since she was three.

Unfortunately, Lesley’s blocked fallopian tubes made their desire to have children of their own unfulfilled. She had been undergoing fertility treatment in Bristol for numerous years. However, traditional treatments had failed, leaving them desperate for a solution.

Therefore the couple decided to try an experimental technique. By chance, her doctor introduced them to Edwards and Steptoe’s work, which sparked optimism. Lesley, a quiet but ambitious lady, began on a trip that would change history.

“My mum simply desired a baby, and she would have pursued it regardless,” Louise reflected.

The birth of a miracle

Their plight led them to Dr. Robert Edwards and Dr. Patrick Steptoe, pioneers in reproductive medicine.

British gynecologist Patrick Steptoe, along with physiologist Robert Edwards and embryologist Jean Purdy, had been researching new reproductive technologies and developed IVF a decade earlier.

In Lesley’s case, the treatment involved extracting an egg from her ovary, fertilizing it with John’s sperm in a petri dish and then implanting the resulting embryo into Lesley’s womb.

Despite numerous failed attempts before Louise’s conception, Lesley was unaware of these failures until late in her pregnancy.

After undergoing many tests and an operation, Lesley’s egg was successfully fertilized and implanted in November 1977. Louise planned a Caesarean section at Oldham District and General Hospital.

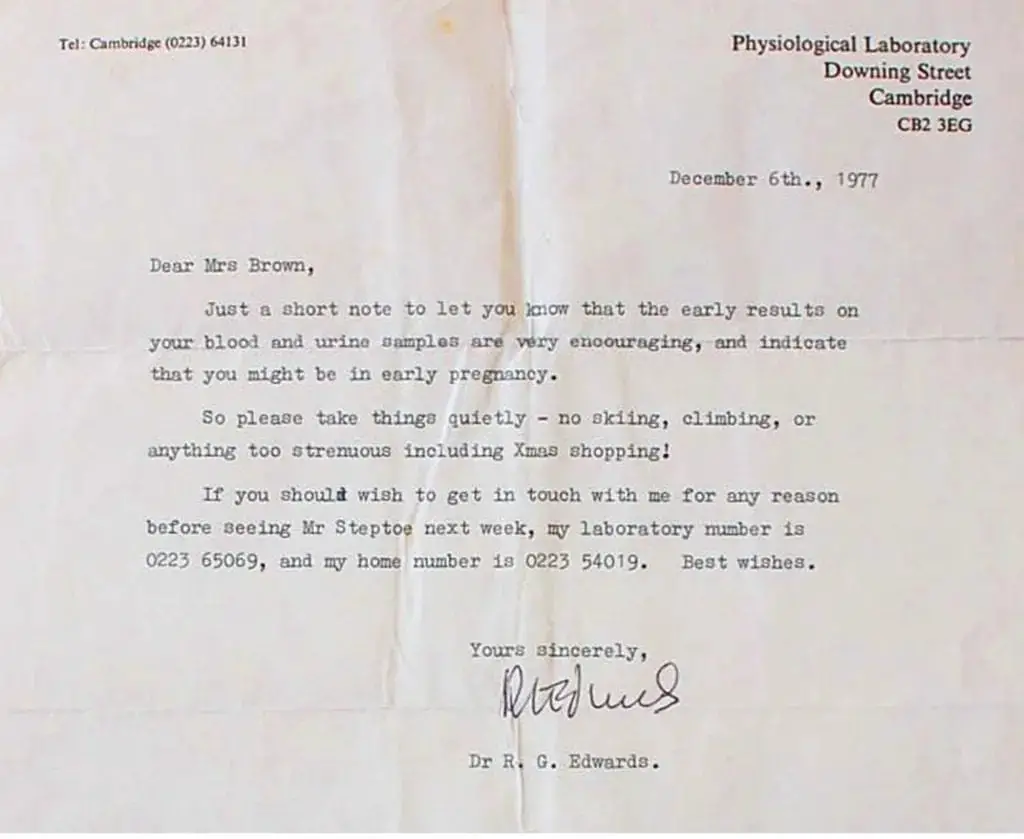

In one letter from December 1977, Dr Robert Edwards wrote: “The early results on your blood and urine samples are very encouraging, and indicate that you might be in early pregnancy. So please take things quietly – no skiing, climbing, or anything too strenuous including Xmas shopping!”

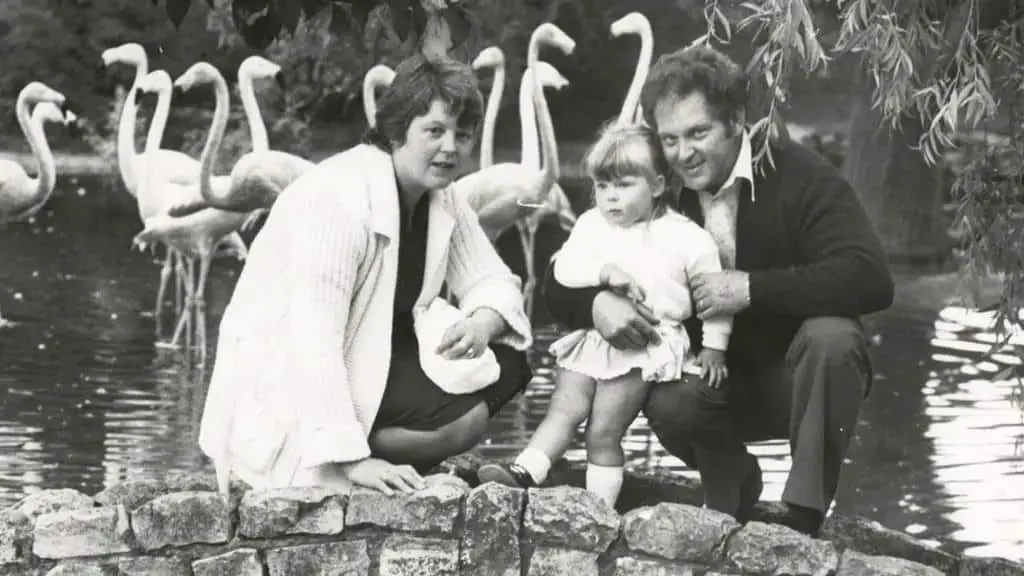

The Browns faced intense public scrutiny when the media knew of the pregnancy. Louise’s birth made headlines worldwide, raising various legal and ethical questions.

In a 2008 interview, Mr. Edwards said, “We were concerned that she would lose the baby because the press were chasing Mrs. Brown all over Bristol where she lived.” To protect her, Patrick Steptoe secretly drove Lesley to his mother’s house in Lincoln, away from the press.

Lesley recalled that once she was in Oldham hospital, reporters tried various methods to sneak into her room, from staging a bomb hoax to posing as cleaners.

How the public reacted to the historic birth

On July 25, 1978, the world eagerly awaited the birth of a baby in Oldham, Greater Manchester. The excitement was so intense that a bomb scare forced the evacuation of patients from Oldham General Hospital.

That day, Louise Joy Brown was born by cesarean section—a healthy baby girl weighing 5 lbs 12 oz.

Louise’s parents were ordinary people, but Louise’s birth made history as the world’s first ‘test-tube baby,’ the result of in vitro fertilization (IVF). This groundbreaking event marked the beginning of an era that has seen around eight million IVF births.

Media interest in Louise’s birth was huge. Even before she was born, Lesley and John received numerous interview requests. To escape the press, they sometimes used fake names.

They signed a deal with The Daily Mail for exclusive coverage, and a company, Chandlewise Limited, was set up to manage media interest. This company sold the story to foreign media, including The National Enquirer.

After Louise’s birth, the Browns received letters of congratulations from around the world. However, they also received hate mail and threatening packages, which worried Lesley.

Louise’s birth also sparked debates about the ethics of IVF and the role of money in journalism. Despite the controversies, her birth remains a significant milestone in medical history.

Louise Brown’s life as the world’s first test tube baby

The attention surrounding Louise Brown continued throughout her life, often overwhelming. She admitted to feeling anxious about her public recognition, especially during her youth when her name was always in the spotlight.

Louise learned about her unique birth at age four, watching a video of her birth with her parents. Despite the challenges, Louise cherished her normal life. She stayed deeply connected to her parents, especially her mother, who protected her from public scrutiny.

Media appearances have been part of Louise’s life since birth. She was first on air in the British TV show “To Mrs. Brown, a Daughter” in 1978, sparking national curiosity.

In 1979, the family traveled with four-month-old Louise to Canada for a TV program about IVF. They also appeared on a Japanese show and visited Florida at The National Enquirer’s invitation.

The book “Our Miracle Called Louise” by Sue Freeman was published in June 1979. That fall, the family toured North America to promote the book, appearing in numerous media outlets.

Other media appearances included a 1983 press conference in America, National Fertility Week in 1993, a symposium in Paris in 1995, an event in Brazil in 2007, and a conference in Bulgaria in 2008.

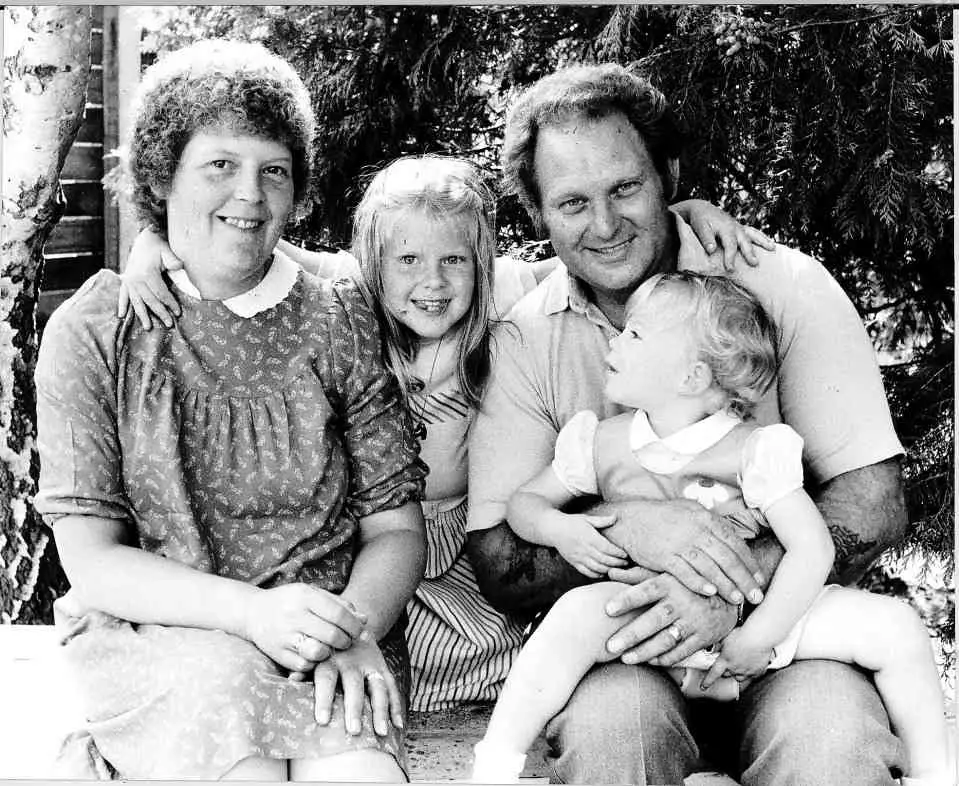

In 1980, Steptoe, Edwards, and Purdy opened Bourn Hall Clinic, the world’s first IVF center. With the clinic’s help, Lesley Brown conceived a second daughter, Natalie, born on June 14, 1982.

In 1999, Natalie became the first IVF-conceived person to give birth naturally. The Brown family stayed in touch with the Bourn Hall team and attended events, including the first “Bourn Hall Baby Party” in 1989 and another in 2003 for Louise’s 25th birthday.

The Brown family lived and worked in Bristol. Louise married Bristolian doorman Wesley Mullinder in 2004. They have two children: Cameron, born in 2006, and Aiden Patrick Robert, born in 2013, named after Steptoe and Edwards.

John Brown passed away in 2006, and Lesley Brown died in 2012.

Since 2007, Louise has been represented by press agent Martin Powell, and she continues to attend IVF events worldwide. The media still covers her birthdays and special occasions.

In 2015, the book “Louise Brown: My Life as the World’s First Test-Tube Baby” was published. Written by Martin Powell, it tells Louise’s story in her own words.

In recent years, internet trolls replaced hate mail, but Louise learned to ignore their hurtful comments. She embraced her place in history, seeing it as a privilege while crediting her courageous mother.

“People thank me for their children, but I accept those thanks on behalf of my mum,” Louise said.

Global impact and legacy

The medical pioneers later became like grandparents to Louise. When she got pregnant with her first child, she wrote to Bob Edwards before anyone else. Now, Louise lives a very normal life in southwestern England with her husband and two sons.

“Not long before mum passed away, she said that without IVF she wouldn’t have anybody left in the world,” says Brown. “Even up to her last days she was proud of who she was and what she did.”

“A few months ago I was in the supermarket with my husband and sons and I heard footsteps running up behind me,” she says. “It was a woman and she had a 4 year-old — the same age as my son — and a tiny baby in a pram. She said that she’d always wanted to thank my mum and me because without us she’d never have had those two. It makes you tear up.”

Today, IVF is a widely used treatment for infertility. Many children around the world have been conceived this way, sometimes with donor eggs and sperm. Over 300,000 babies have been born through IVF in the UK since Louise Brown.

According to the NHS, Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority, the success rate of IVF has increased from 8% in 1991 to 21% in 2016. One in seven couples struggles to conceive, and 16% of IVF pregnancies result in twins or more.

Women’s fertility declines after age 35, and men’s fertility declines after age 40. The average age of women getting IVF has risen from 33.6 in 1991 to 35.5 today