Dorothy Catherine Draper is a truly forgotten figure in American history. In 1839, she became the first woman to sit for a photograph—a daguerreotype—taken by her brother, John William Draper, on the rooftop of a school. This pioneering moment in photography marked a significant milestone.

She spent her whole life focusing on caring for her beloved ones, supporting her brother’s scientific work and taking care of his family. Dorothy’s life, full of dedication and sacrifice, deserves recognition as an important part of early American scientific history.

Dorothy’s dedication to her family

Dorothy Catherine Draper was born on August 6, 1807, in St. Helens, Lancashire, England. Her parents were John Christopher Draper, a Wesleyan clergyman, and Sarah Ripley Draper.

The Draper family, consisting of Dorothy, her two sisters Elizabeth and Sarah, and her brother John William Draper, enjoyed a happy life in early 19th-century England.

Dorothy’s father frequently moved the family as he served different congregations throughout England. These constant relocations brought the siblings closer together.

After her father’s passing in February 1829 in Kent, Dorothy, her mother, and her siblings moved to Virginia. They followed her brother John, who sought a teaching position at a local Methodist college.

Although John William Draper missed out on the teaching job he wanted, he set up a lab in Christiansville. He published eight papers there before starting medical school.

Dorothy Catherine Draper played a crucial role during this time. She supported John’s medical education by teaching drawing and painting. In March 1836, John graduated from the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine and began teaching at Hampden-Sydney College in Virginia that same year.

Dorothy was more than just a sister; she became John’s lifelong assistant, sharing his interests in scientific research and “rendering him valuable aid.”

She never married, so all her free time was spent on taking care of her loved ones. When her brother’s wife fell ill, Dorothy stepped in as a mother figure to their children, homeschooling and nurturing them. She supported her brother’s work tirelessly. They lived together peacefully and happily.

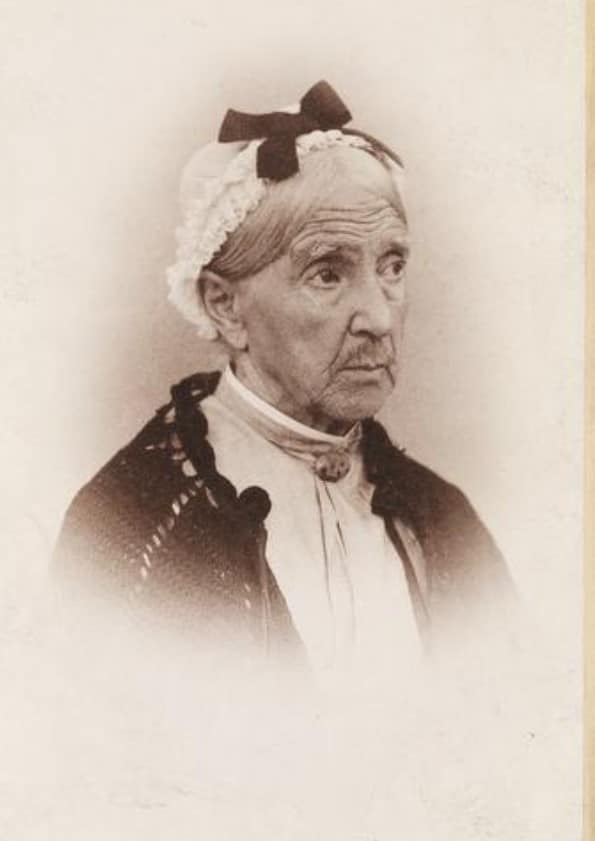

Dorothy passed away in December 1901 at the age of 94, at the Draper family home in Hastings-on-Hudson, New York. She was laid to rest alongside her brother and sister-in-law in Green-Wood Cemetery, Brooklyn, New York.

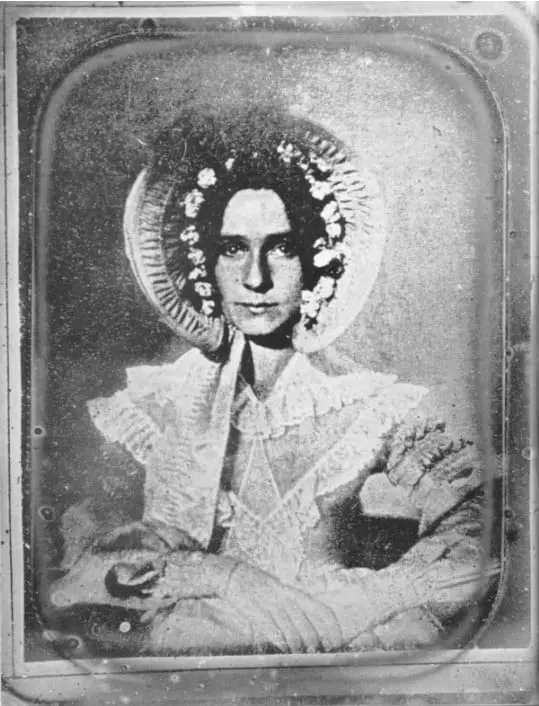

The timeless portrait of Dorothy

John William Draper made significant advances in photochemistry, improving on Louis Daguerre’s process and helping to establish portrait photography. He produced some of the first clear photographs of human faces.

In 1839, in his Washington Square studio at New York University, Draper took a series of pictures with a 65-second exposure in sunlight, shortly after Daguerre’s announcement of the daguerreotype process in Paris.

In 1840, Dorothy Catherine Draper sat for a photograph taken by her brother, John. For the 65-second exposure, Dorothy had to keep her eyes open without blinking, and her face was dusted with white flour to enhance the contrast.

This photograph gained public attention through a letter John sent to John Herschel, an experimental photographer known for inventing the blueprint in 1840.

During the 19th century, several copies of Dorothy’s photograph were made, with one likely being a copy created by John himself.

Less-Known facts about Dorothy Catherine Draper

Dorothy was an excellent teacher

She created the colored plates for his memoirs and homeschooled his children. Her efforts clearly paid off, as her nephews achieved great success in their fields.

One became a surgeon and chemist, another pursued a career as a doctor and amateur astronomer, and a third gained recognition as a meteorologist.

In fact, this nephew honored Dorothy by naming his daughter after her. Dorothy’s dedication to education helped shape a truly remarkable family.

She is the first woman named in most records of the University Building

A researcher exploring the history of the University Building might initially think women were only allowed in as servants or in disguise, similar to the character in the 1861 novel “Cecil Dreeme.” The University of the City of New York, based in the building, didn’t admit women students for most of its time there.

The building’s most famous residents, like Samuel F. B. Morse and Samuel Colt were all men. Did 19th-century views on gender roles really exclude women from the building’s intellectual life? While that may have been the intent, the reality was more complex.

Dorothy Catherine Draper appears prominently in historical accounts of the University Building as its first noted female figure. In 1839, she famously sat for one of the earliest daguerreotypes of a human face, captured by her brother, Professor John William Draper, on the building’s rooftop.

Though educated herself, Dorothy’s presence inside the University Building was a rare event, only made possible because her brother accompanied her. After the day she was immortalized in this early American photograph, there are no further records of her visiting the building.