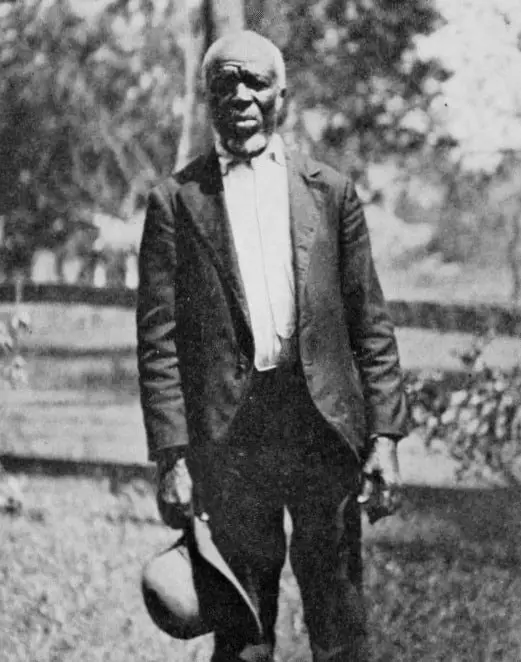

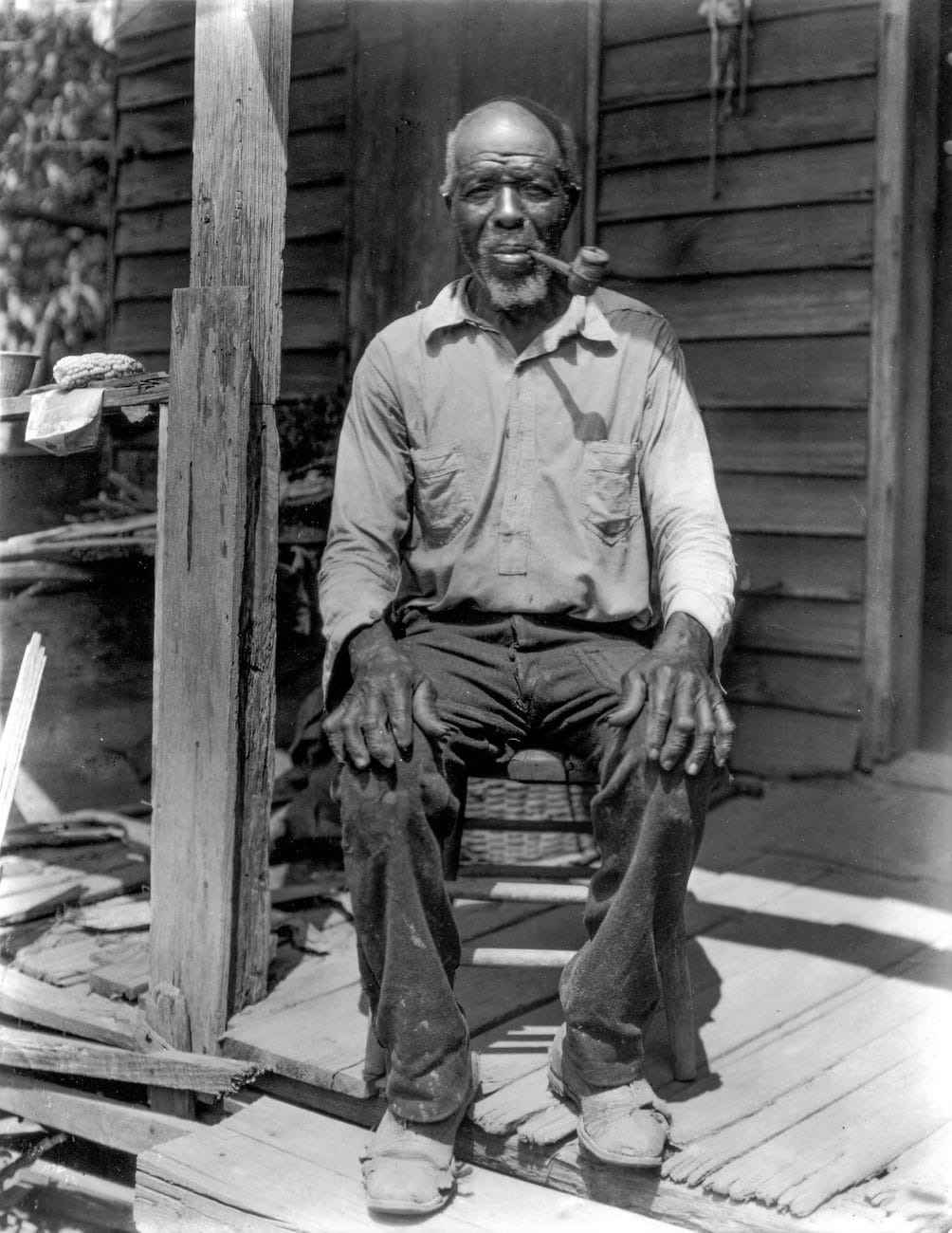

Cudjo Lewis (ca. 1841-1935) was one of the last survivors of the Clotilda, the final documented slave ship to illegally transport enslaved Africans to the United States.

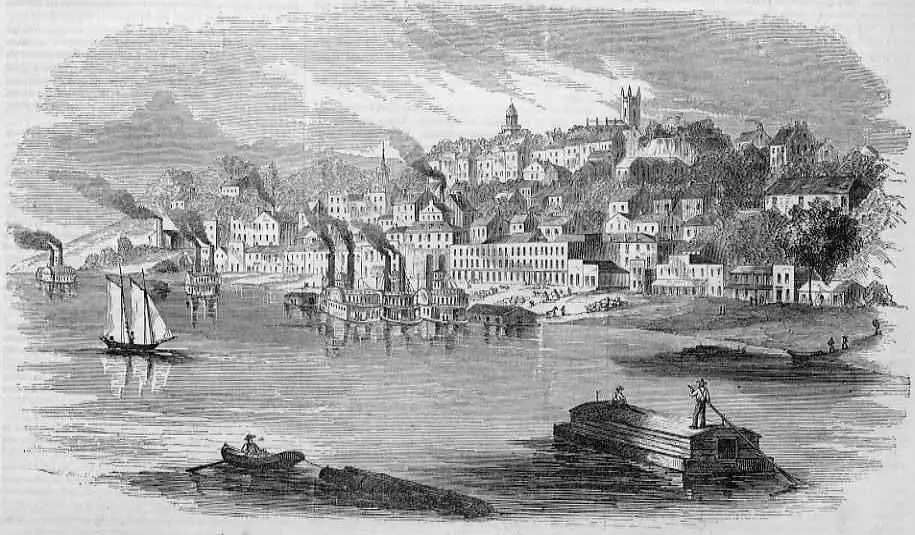

Despite the country having banned the international slave trade 52 years earlier, the Clotilda arrived in Mobile on July 8, 1860, under the cover of darkness. This clandestine voyage underscores the enduring horrors of the transatlantic slave trade, which forcefully moved millions of Africans to the Americas.

In his lifetime, Cudjo witnessed dramatic changes, from his peaceful childhood in Africa to the harsh life of a slave and eventually to a freed but restricted life. His home, family, beliefs, and even his name underwent profound changes.

Yet, despite these hardships, Cudjo found peace and learned to accept the difficult life he was forced to endure. Discover his tale that resonates with both historical significance and personal courage.

Oluale Kossola had a happy and active childhood

Cudjo Lewis, originally named Oluale Kossola, was born in modern-day Benin, West Africa, to Oluale and his second wife, Fondlolu. He grew up in a large family with five full siblings and twelve half-siblings from his father’s other marriages.

Historian Sylviane Diouf suggests that Cudjo and many others in Africatown were Yoruba people from the Banté region of Benin, based on their names and other aspects of their culture.

Kossola came from a modest background, but his grandfather held a respected position as an officer in the local king’s court. He and his siblings enjoyed a happy and active childhood.

At the age of 14, Kossola began training as a soldier, learning skills such as tracking, hunting, camping, archery, spear throwing, and defending his town. He was also initiated into oro, a secret Yoruba male society responsible for maintaining order in the community.

By 19, Kossola had fallen in love with a girl he met at the market, prompting his father to encourage him to undergo initiation rites that prepared young men and women for marriage. He was becoming a respected member of his tribe, deeply ingrained in his community’s traditions and values.

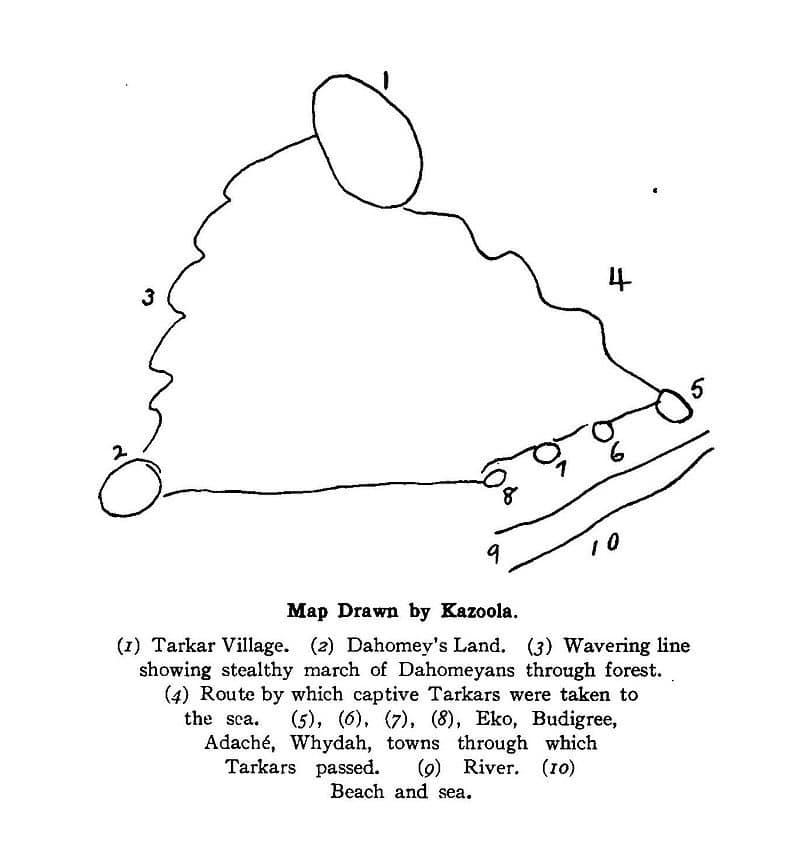

Kossola was sold into slavery by a West African King

In April 1860, while Kossola was still in training, King Ghezo of Dahomey attacked his town. They killed the king and many others, taking the rest, including Kossola and his neighbors, as prisoners.

They were marched to Dahomey’s capital, Abomey, and later to Ouidah. There, they were held for three weeks in a barracoon, a prison for captives, before they were shipped across the Atlantic.

After that, Kossola and others from Benin and Nigeria boarded the Clotilda, a slave ship captained by Mobile shipbuilder William Foster. During the brutal 45-day Middle Passage journey, Kossola endured terrible thirst and the humiliation of being forced on board naked.

The ship arrived in Alabama in 1860, just before the Civil War began. Although the United States had banned the international slave trade over 50 years earlier, in 1807, Lewis’ story shows how traders continued to smuggle slaves.

To avoid detection, Lewis and the others were sneaked into Alabama at night and hidden in a swamp for days.

The Clotilda was then burned on the banks of the Mobile-Tensaw Delta to destroy evidence of the illegal journey, though its remains were possibly found in January 2018.

Lewis vividly described the traumatic experience of slavery firsthand. Taken from his home and forced onto a ship with strangers, he spent months on the perilous journey to the United States.

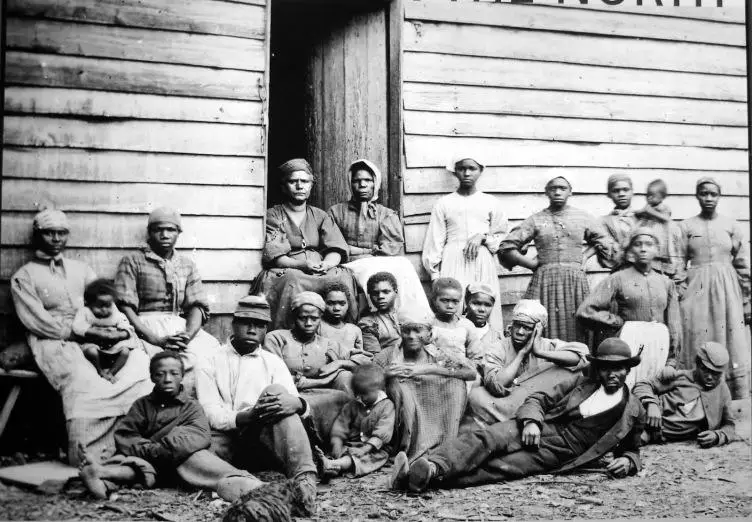

Upon arrival, he and the others were separated and sold to different owners in Alabama.

“We were very sorry to be separated from each other. We spent seventy days crossing the water from Africa, and now they separate us. That’s why we cried. Our sadness was so heavy it felt like we couldn’t bear it. I thought maybe I would die in my sleep dreaming about my mama,” Lewis recounted.

Cudjo endured four years of slavery

In Mobile, Cudjo was enslaved by James Meaher, a wealthy ship captain and brother of Timothy Meaher, who organized the expedition.

Unable to pronounce Kossola’s name, James Meaher called him Cudjo, a name used by the Fon and Ewe peoples of West Africa for boys born on Monday.

Cudjo also recalled arriving at a plantation where no one spoke his language or could explain why they had been taken from their country to work like this.

He said, “We doan know why we be bring ’way from our country to work lak dis. Everybody lookee at us strange. We want to talk wid de udder colored folkses but dey doan know whut we say.”

He worked at Meaher’s shipyard with other slaves until the end of the Civil War in 1865, when the Confederate army surrendered.

Cudjo mentioned they had no knowledge of the war, but a few days after it ended, Union soldiers came by where they were working and informed them of their freedom.

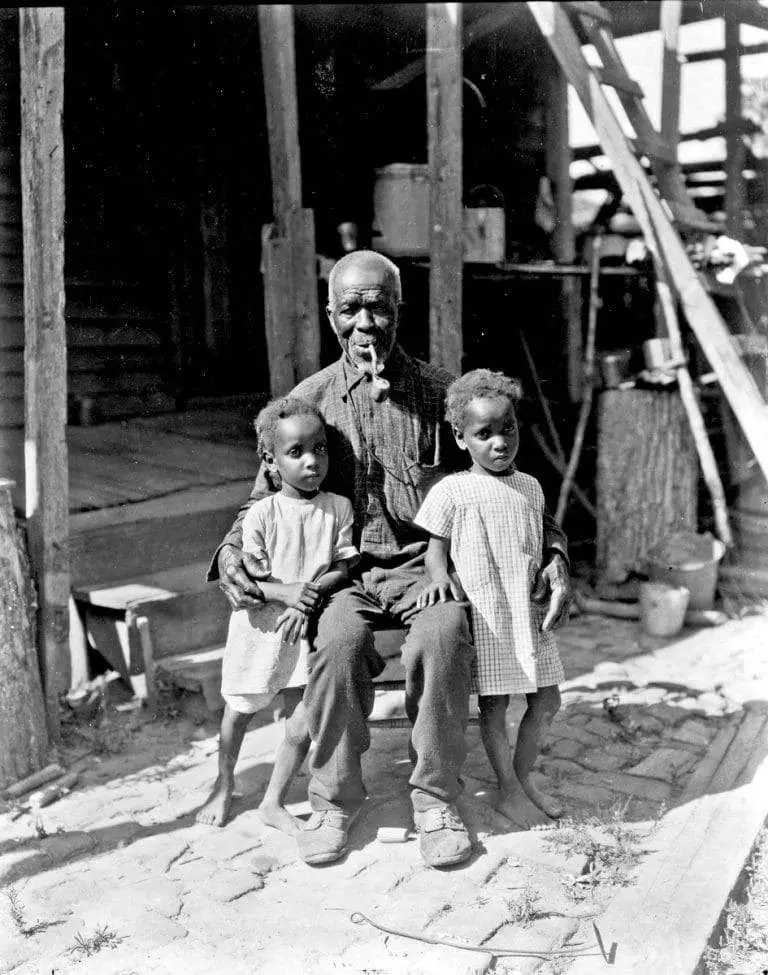

Cudjo Lewis created a home away from home in Alabama

In 1865, after gaining freedom with the general emancipation, Cudjo took the name Lewis. He married Abile, who also survived Clotilda. Their plan was to return home, but they lacked the money for the journey.

Lewis hoped for compensation for being taken as a slave, but emancipation did not bring promised land or reparations. Disappointed, he and 31 others saved money to buy land near Mobile, naming it Africatown.

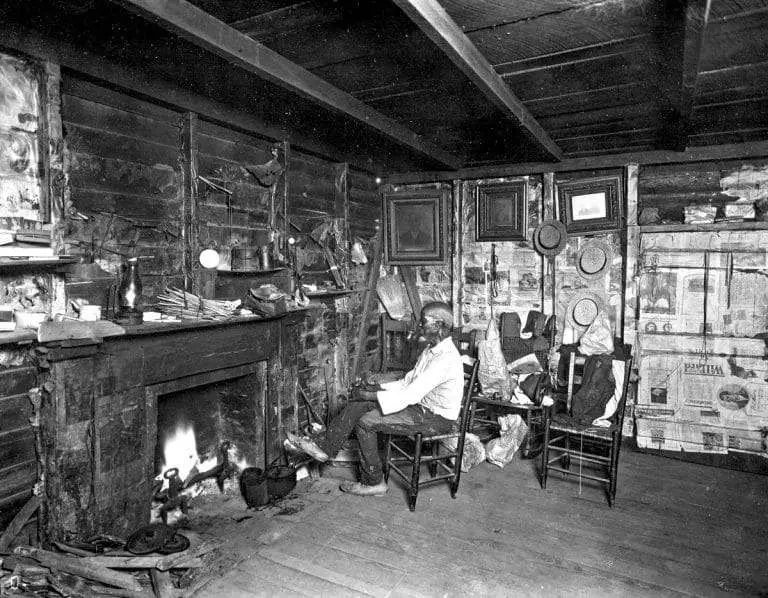

Cudjo worked as a farmer and laborer to support his family until a train accident in 1902 left him injured. He then became the caretaker of the community’s Baptist church. Cudjo and Abile had six children, but tragically, all died young. Abile passed away in 1908.

Africatown wasn’t just a refuge for former slaves; it was a self-sustaining community with its own laws, language, and shared African values. They established a school, church, and cemetery.

It became a sanctuary for both African descendants and immigrants. As Historian Diouf noted, “Black towns provided safety from racism, but Africatown offered refuge from Americans.”

Despite finding much he needed in America, Cudjo struggled spiritually for a long time. His African beliefs differed greatly from Southern Christianity, and he sought a connection to his higher power. Eventually, he embraced Christianity and found solace in the Baptist church.

Cudjo Lewis gained some small fame at the end of his life

At the start of the 20th century, Cudjo began sharing his incredible story with scholars and writers interested in spreading his history worldwide. By 1925, he was noted as the last survivor of the Clotilde and had been featured in several non-fiction works.

In 1927, author Nora Neale Hurston interviewed him, capturing photos and the only known film of an African enslaved and brought to America. Cudjo Lewis passed away on July 17, 1935, and was laid to rest at Plateau Cemetery in Africatown.

Today, a tall white monument marks his grave, and some of his descendants still reside in Mobile. Sally “Redoshi” Smith and Matilda McCrear, the last survivors from the group, lived until 1937 and 1940, respectively.