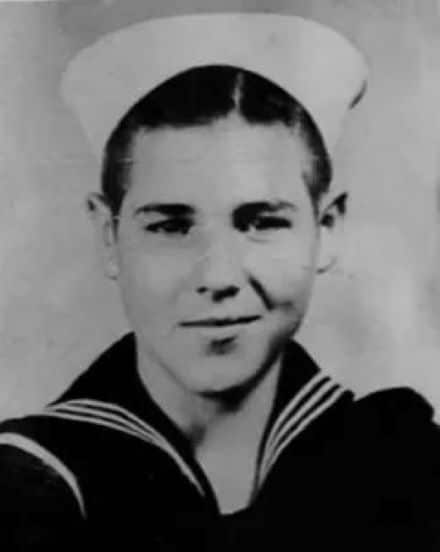

War creates unexpected heroes regardless of age, gender, or skin color. Among these brave souls, Calvin Graham shines as a remarkable figure.

At 11, he started shaving and practicing a deep voice to look and sound older. Unlike other boys pretending for fun, Calvin had a unique goal: to join the U.S. military and fight in WWII.

He had recently moved into a boarding house with his brother to escape an abusive father and an overcrowded home. During this time, Calvin worked several jobs to support himself and rarely saw his mother.

His independence and determination drove him to join the war effort at just 12 years old. Scroll down to explore the journey of this young Navy hero.

How Calvin Graham bluff his way into the Navy

Boys had to be at least 17 to enlist in the war or 16 with a parent’s consent. But Calvin Graham, undeterred by his age of just 12, took matters into his own hands.

Along with two friends, he forged his mother’s signature on enlistment papers and stole a notary stamp from a local hotel. Telling his mother he was visiting relatives, he instead lined up to enlist in the Navy in Houston, Texas, on August 15, 1942.

The biggest challenge for Graham wasn’t forging the signature; it was getting past the enlistment dentist, who could easily tell his true age by examining his teeth. Calvin had a plan. He lined up behind two boys he knew were only 14 and 15. When the dentist questioned his age, Calvin pointed out that the boys ahead of him were also underage but had been allowed through. “Finally,” Graham recalled, “he said he didn’t have time to mess with me, and he let me go.”

Graham later explained his motivation: “I didn’t like Hitler to start with.” Learning that some of his cousins had died in battles, he felt a strong urge to fight.

Despite being only 5’2″ and 125 pounds, Calvin dressed in his older brother’s clothes and practiced speaking in a deep voice. His determination paid off, and he was accepted into the Navy.

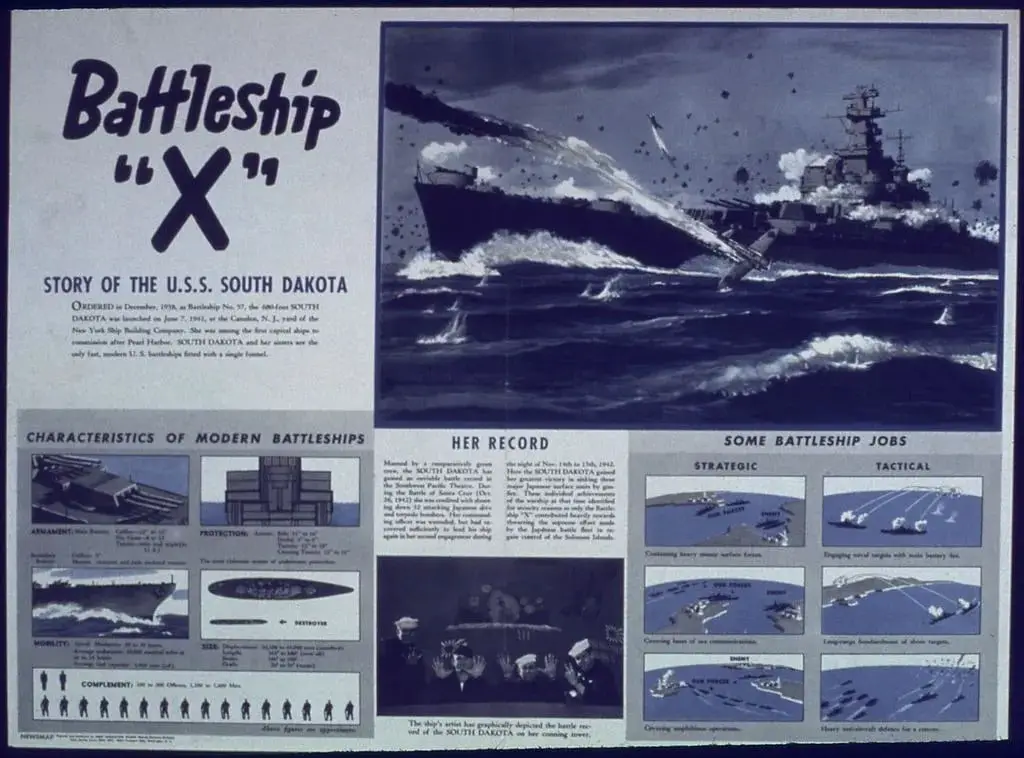

Once in training, the drill instructors were aware that some recruits were underage and punished them with extra miles to run and heavier packs to carry. Despite this, Calvin persevered and was assigned to the USS South Dakota, a battleship working in the Pacific alongside the USS Enterprise.

Marine Henry Buecker met Graham aboard the South Dakota. “Calvin asked me: ‘Can you keep a secret? I’m 15,’” Buecker later recalled. “I didn’t find out he was only 12 until 35 years later.”

Graham earned the Bronze Star and Purple Heart for bravery

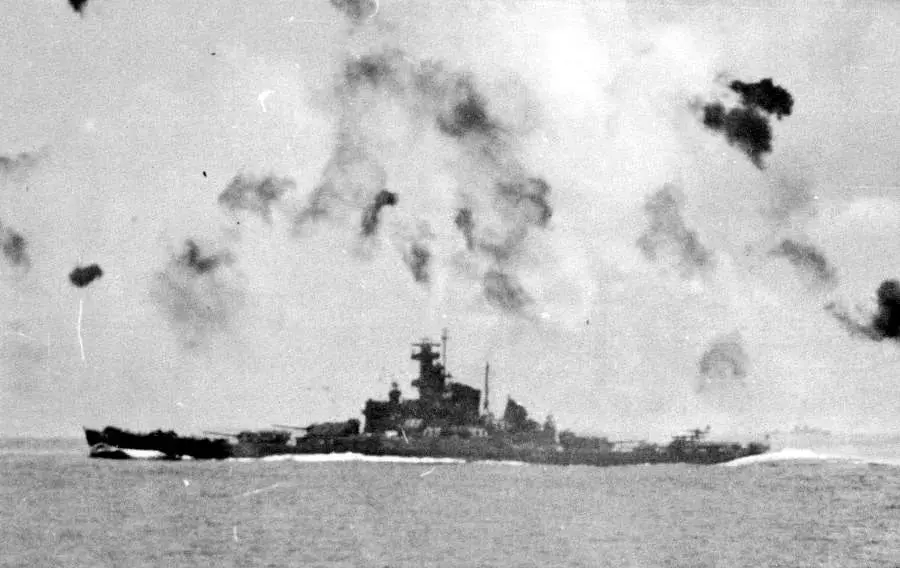

The USS South Dakota became famous for its aggressive Captain Thomas Gatch and its young, inexperienced crew known as “green boys.”

Soon after the Battle of Santa Cruz, the ship faced eight Japanese destroyers and took 42 hits during the Naval Battle of Guadalcanal.

While manning his gun, shrapnel tore through Graham’s jaw and mouth, and he fell three stories through the ship’s superstructure. Despite his injuries, he stood up, dazed and bleeding, and helped pull other crew members to safety, even as explosions threw others into the sea.

“I took belts off the dead and made tourniquets for the living and gave them cigarettes and encouraged them all night,” Graham remembered. “It was a long night. It aged me.”

He lost his front teeth and suffered burns but received only basic first aid as the ship’s casualties were prioritized. The battle left 38 men dead and 60 wounded.

The South Dakota inflicted heavy damage on the Japanese ships before disappearing into the smoke. After the battle, the South Dakota returned to the Brooklyn Navy Yard for major repairs.

Captain Gatch praised his young crew, saying, “Not one of the ship’s company flinched from his post or showed the least disaffection.” Calvin Graham received a Bronze Star for his bravery in combat and a Purple Heart for his injuries.

Graham spent three months in a Texas brig

Calvin Graham couldn’t join in the celebrations with his fellow crew while their ship was being repaired. His mother saw him in a newsreel and reported his true age to the Navy.

The Navy acted quickly, stripping Graham of his medals and holding him in a military prison in Corpus Christi, Texas, for nearly three months.

While the USS South Dakota continued its mission in the Pacific, Graham managed to send a message to his sister Pearl. She wrote to the newspapers, accusing the Navy of mistreating her brother, a “baby vet.”

Under public pressure, the Navy eventually released Graham. He was let go with just a suit, a few dollars, and no honorable discharge.

His service and sacrifice were finally honored after 35 years

Back in Houston, Calvin Graham was treated like a celebrity. Reporters flocked to tell his story, and when the war film “Bombardier” premiered at a local theater, the star, Pat O’Brien, invited Graham onstage to be saluted by the audience. However, the attention quickly faded.

At 13, Graham tried to return to school but couldn’t keep up and dropped out. He married at 14, became a father at 15, and worked as a welder in a Houston shipyard. His job and marriage didn’t last. By 17, he was divorced and about to be drafted.

After breaking his back while serving in the Marine Corps during the Korean War, he sold magazine subscriptions to make a living.

In 1976, things changed when Jimmy Carter was elected president. Graham wrote to the White House about his experience, hoping for sympathy from a fellow Navy man. He felt he deserved an honorable discharge more than deserters did.

Finally, in 1978, Carter announced that the bill to grant Graham’s discharge had been approved, and his medals were restored. In 1988, he was granted disability benefits and back pay, except for the Purple Heart, which was returned to his family in 1994, two years after Graham died of heart failure at age 62 on November 6, 1992, in Fort Worth, Texas.