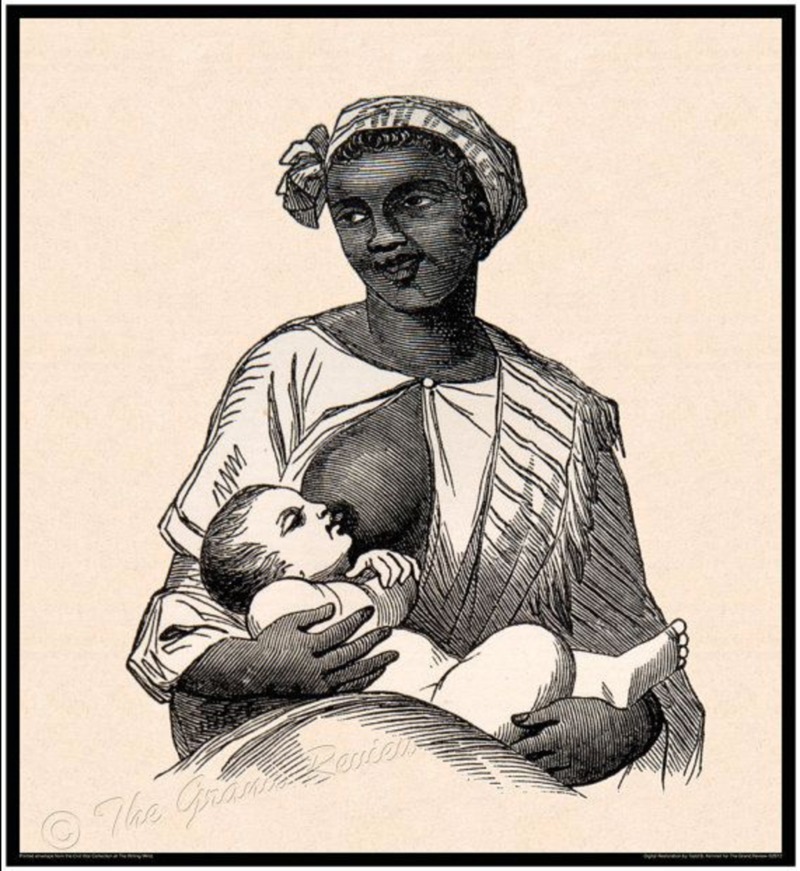

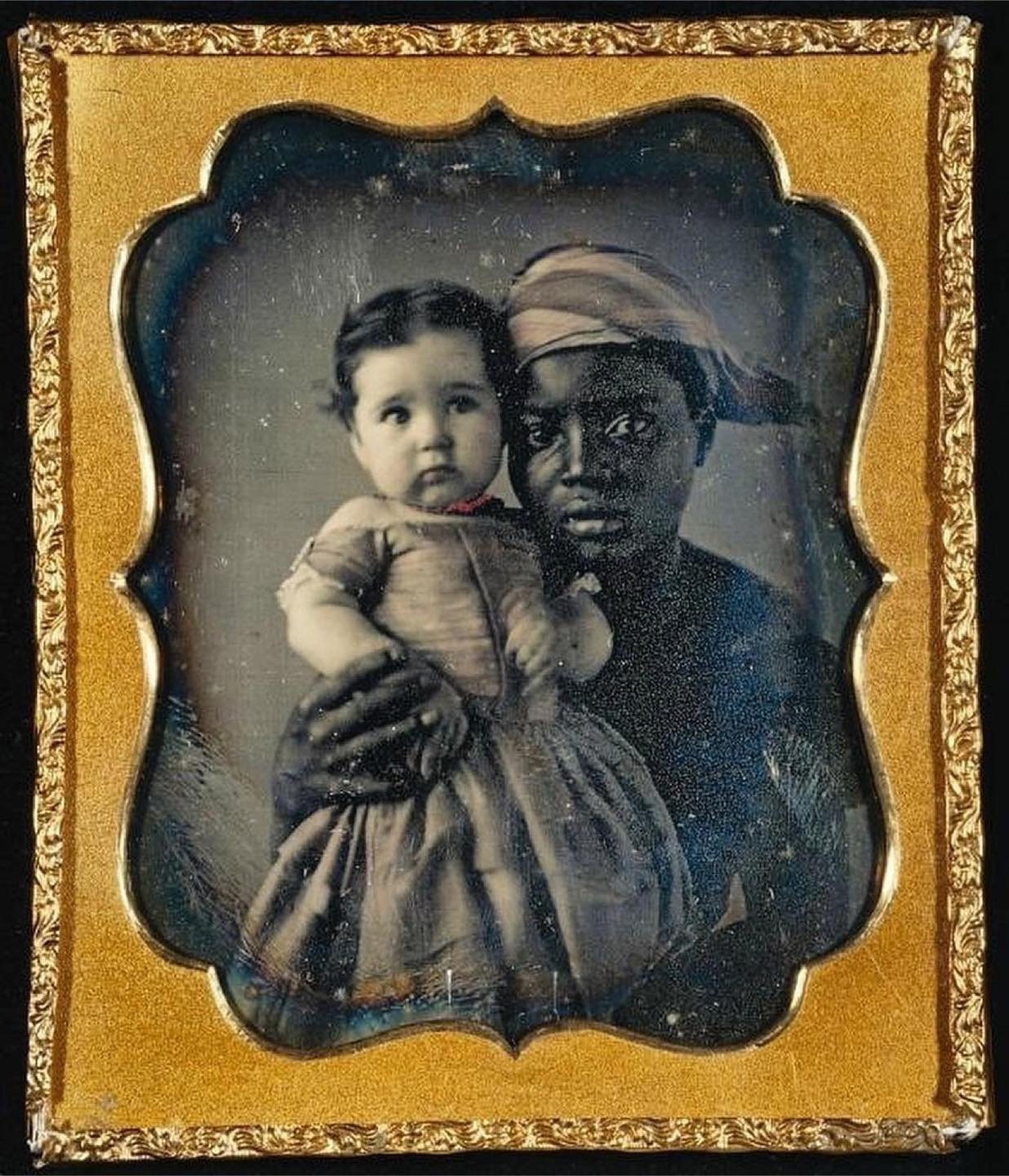

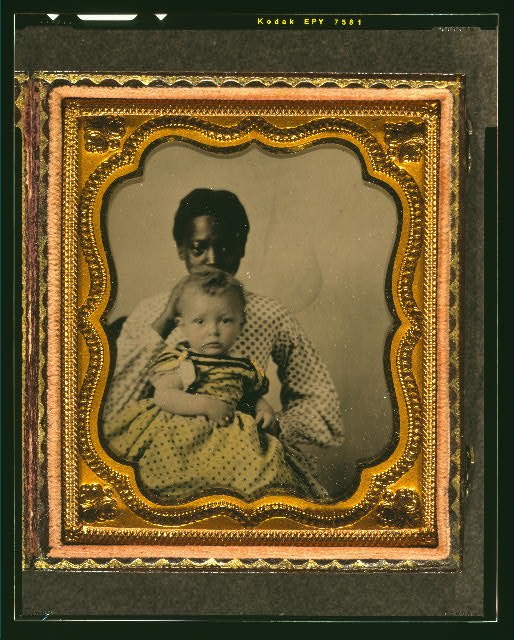

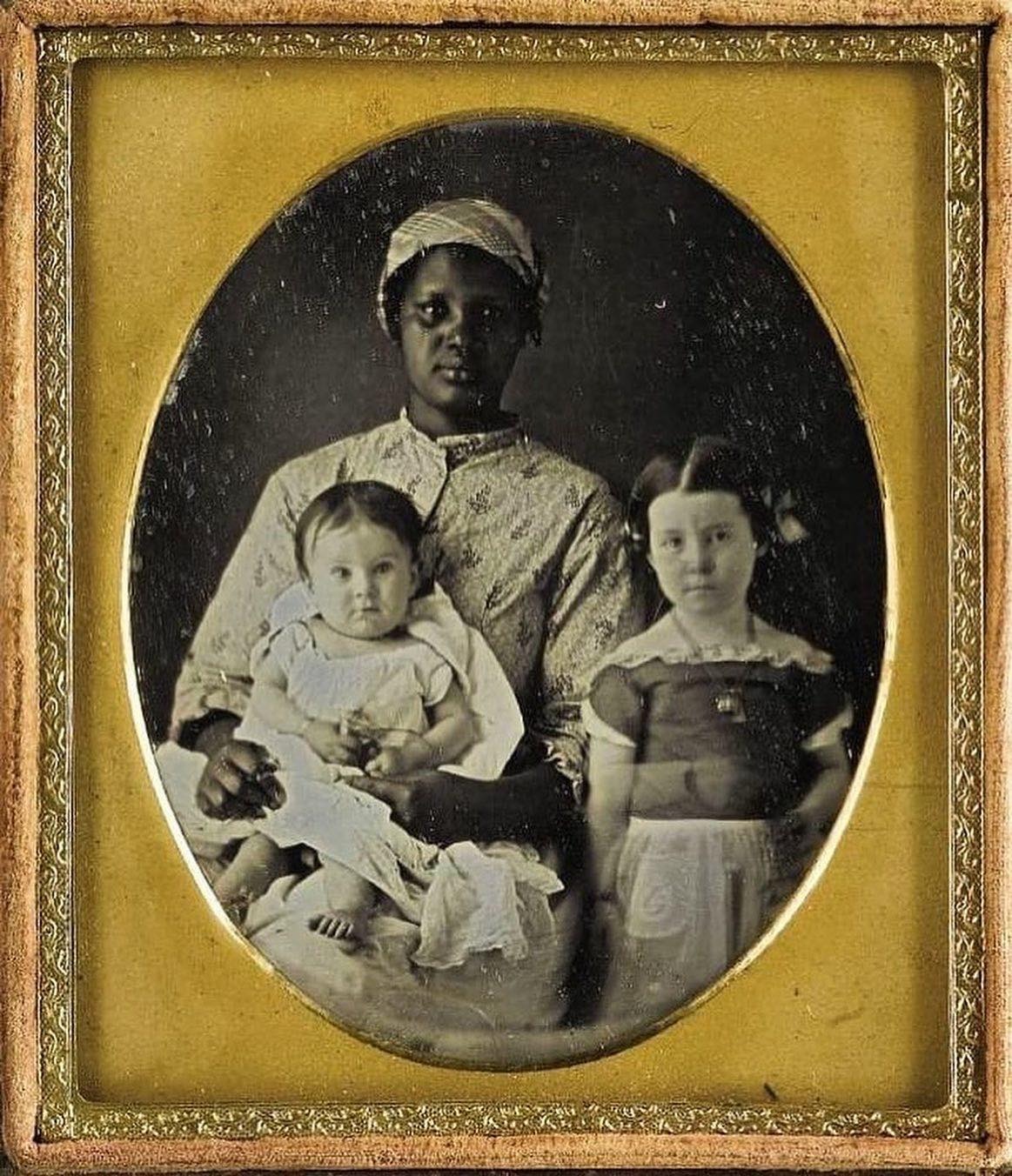

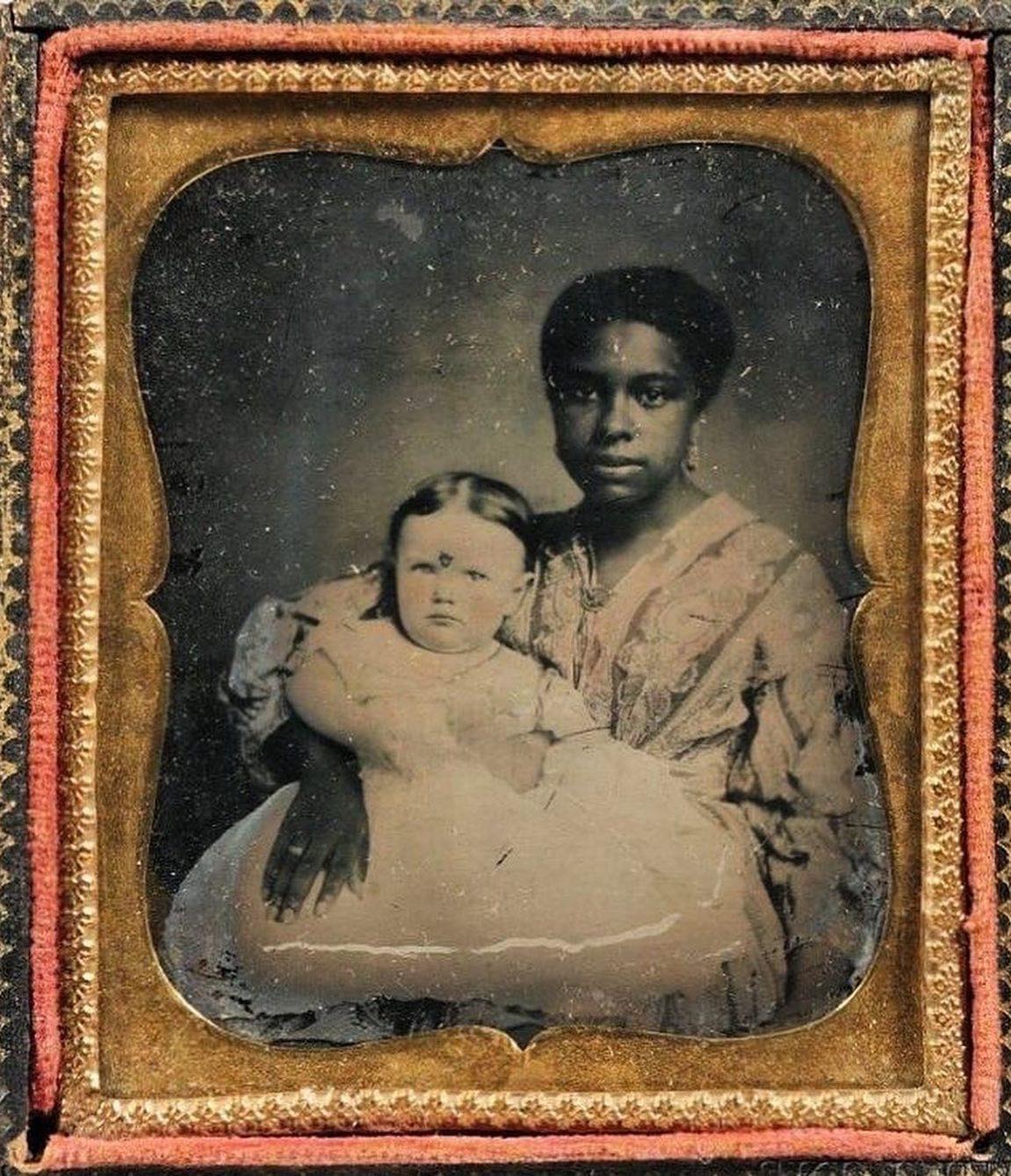

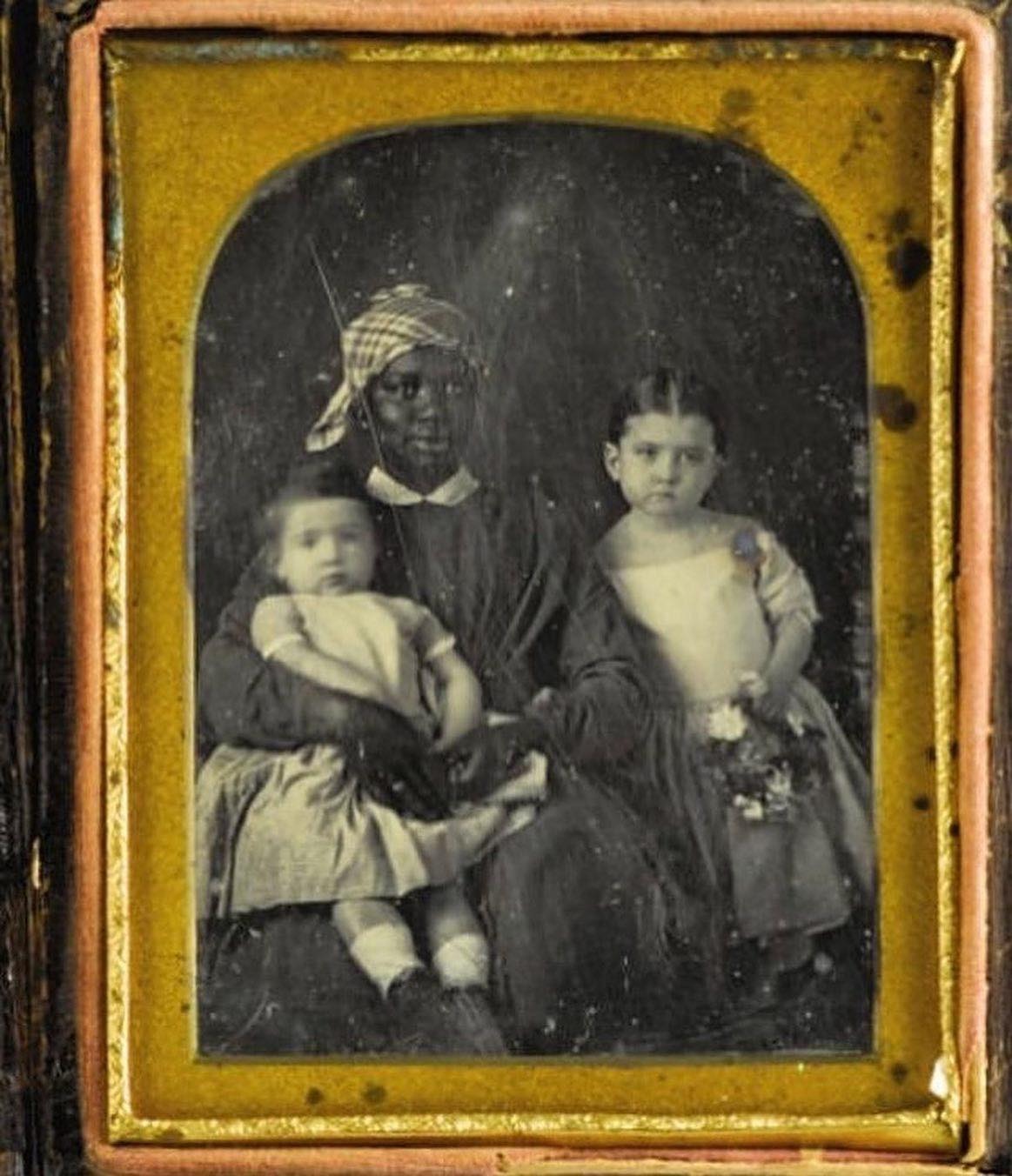

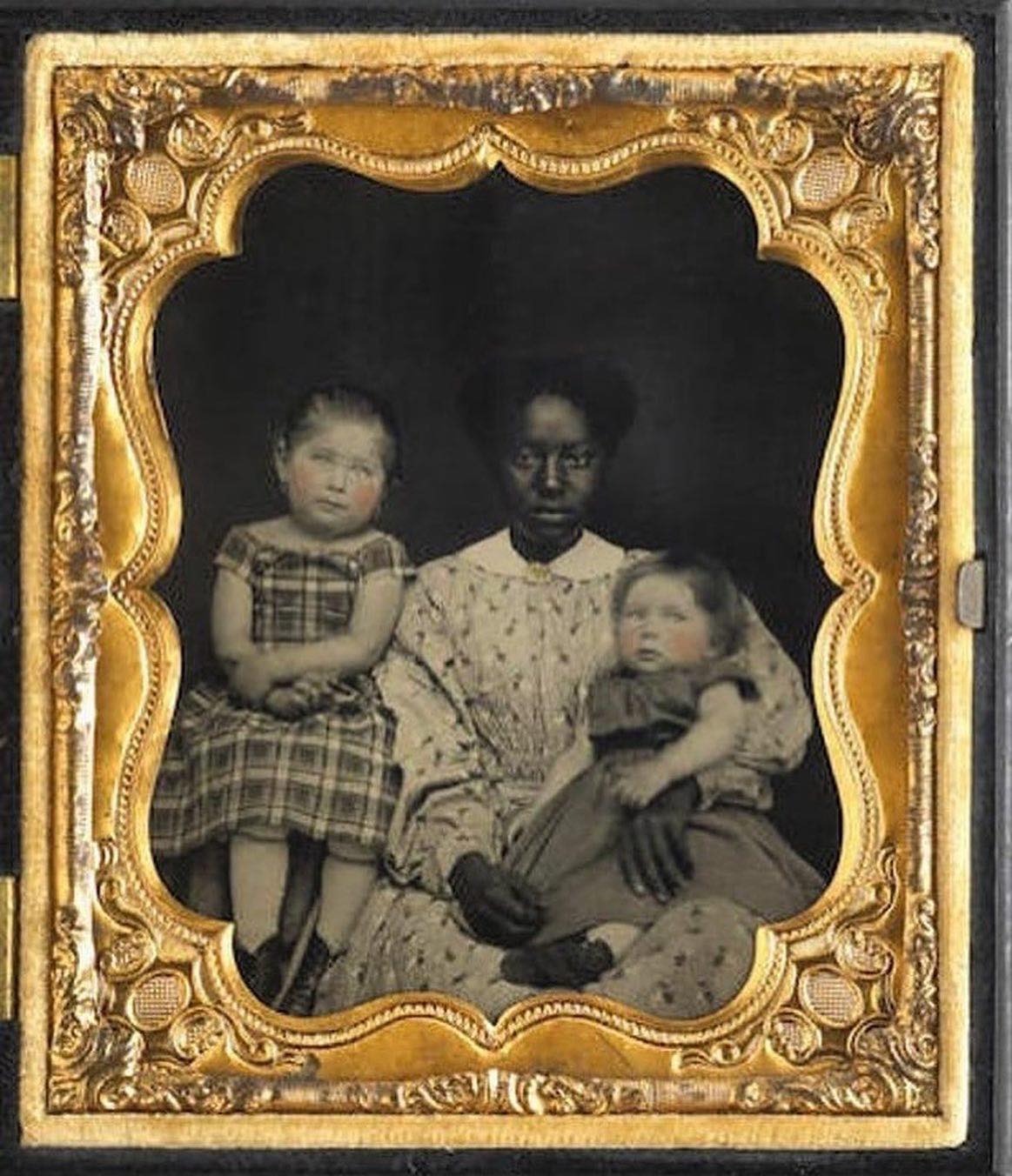

When you first glance at those old, sepia-toned photographs of black nursemaids cradling white children, they evoke a sense of warmth and nostalgia.

The serene smiles and tender embraces captured in these images often give the impression of a deep bond, perhaps even a mutual affection that transcended race and class.

But under the surface of these seemingly heartwarming scenes lies a far more complex and heartbreaking reality because they mask a history of relentless labor, exploitation, and the enduring scars of slavery.

The reality behind the “Mammy” myth

In the folklore of the American South, the black nursemaid, often called “Mammy,” is portrayed as a loving, selfless figure who cherished the white children in her care as if they were her own.

But inside this romanticized facade lies a far grimmer reality—one steeped in relentless labor, minimal pay, and a life that, in many ways, was a continuation of the shackles of slavery.

One such account from a black nursemaid published in The Independent in 1912 dispels the comforting “Mammy” myth. She stated plainly, “We are literally slaves”.

These nursemaids were trapped in a cycle of never-ending work, waking before the sun and toiling long after it set, nurturing their employers’ children while their own were left to fend for themselves.

Their days blurred into nights, with only a few hours of stolen sleep, all for a meager wage. Yet, their labor was dismissed as mere obligation, their sacrifices overlooked, and their voices silenced.

A life of sacrifice and exploitation

The daily life of a black nursemaid in the 1800s was grueling. One said: “I frequently work from 14 to 16 hours a day. I am compelled by my contract, which is oral only, to sleep in the house…”

These women were responsible for the full care of the children in their charge—feeding, bathing, clothing, and often even sleeping in the same room to attend to the child’s needs during the night.

But their duties didn’t stop there. They were also expected to perform various household chores, from cooking and cleaning to running errands.

One nursemaid recalled her experience, stating, “I wash and dress the baby two or three times each day, I give it its meals, mainly from a bottle; I have to put it to bed each night; and, in addition, I have to get up and attend to its every call between midnight and morning.”

These women were often separated from their own children and allowed to see them only on rare occasions. The same nursemaid revealed the heartbreaking reality:

“I am allowed to go home to my own children… only once in two weeks.” This forced separation took a heavy emotional toll on these mothers as they had to nurture the children of those who enslaved them while their own children suffered.

Behind the gentle smiles captured in photographs were women who lived under constant fear and oppression. Many were subjected to physical and sexual abuse, and their virtue was routinely disregarded.

One nursemaid courageously revealed, “I was dismissed because I refused to let the madam’s husband kiss me.” The refusal to submit to such advances often led to punishment, dismissal, or worse.

The misrepresentation and cultural legacy

The way these nursemaids have been portrayed in culture has been heavily shaped by the “Mammy” archetype. This caricature painted them as loyal and contented servants, happily devoted to their white families.

However, this stereotype was far from reality, yet it remained a common image in popular culture for many years.

The “Mammy” figure became a fixture in the Southern imagination, appearing in everything from books to advertisements, suggesting that black women were naturally suited to servitude.

But as the nursemaid from “The Independent” pointed out, this image was a serious misrepresentation: “We are fighting a terrible battle, and because of our weakness, our ignorance, our poverty, and our temptations we deserve the sympathies of mankind.”