Just before Halloween in 1948, Donora, a bustling steel town in western Pennsylvania, faced an unusual and dangerous weather event.

This event would not only challenge first responders but also mark the beginning of significant changes in environmental policies.

During this fateful week, Donora’s 14,000 residents continued their daily routines, unaware that they were living through one of the worst public health and environmental disasters in U.S. history.

The combination of industrial emissions and a dangerous weather phenomenon trapped toxic pollutants close to the ground and created a lethal fog.

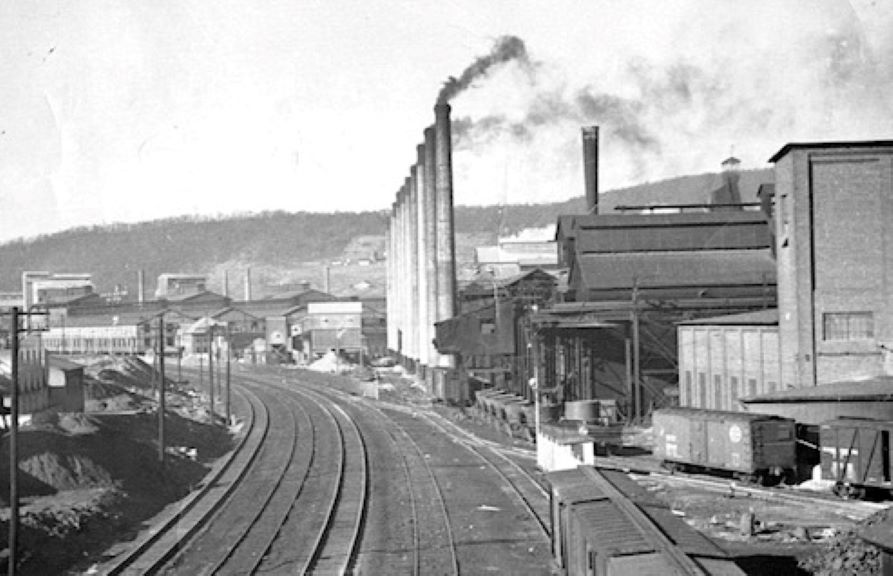

The industrial heartbeat of Donora

In 1948, Donora was a bustling industrial hub, several times larger, and home to a zinc works with ten smelters and a steel mill.

These plants provided good-paying jobs to thousands but at a significant cost. Workers were paid for a full day’s work but could only work a few hours due to the risk of “zinc shakes,” a term for the illness caused by zinc exposure.

The plants released a mix of harmful pollutants, including hydrogen fluoride, carbon monoxide, nitrogen dioxide, sulfur compounds, and heavy metals.

This pollution had devastating effects not just on the workers but also on the environment.

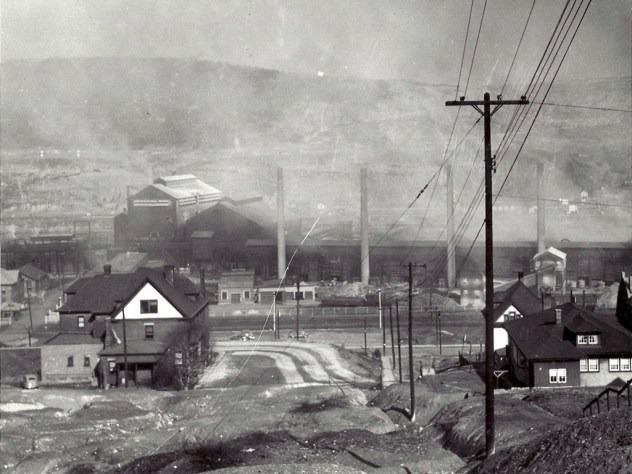

In the nearby village of Webster, pollution destroyed local orchards, and in Donora, it killed vegetation, caused severe erosion, and rendered a local cemetery unusable.

Before the infamous smog incident, Donora was a proud industrial town, much like its sister city, Pittsburgh. Residents relied heavily on the industrial plants for their livelihood.

Many of its residents were immigrants who had endured World War I, the Great Depression, and World War II.

As Mark Pawlewec of the Donora Historical Society explained, “Donora was a self-contained town … everything was here.”

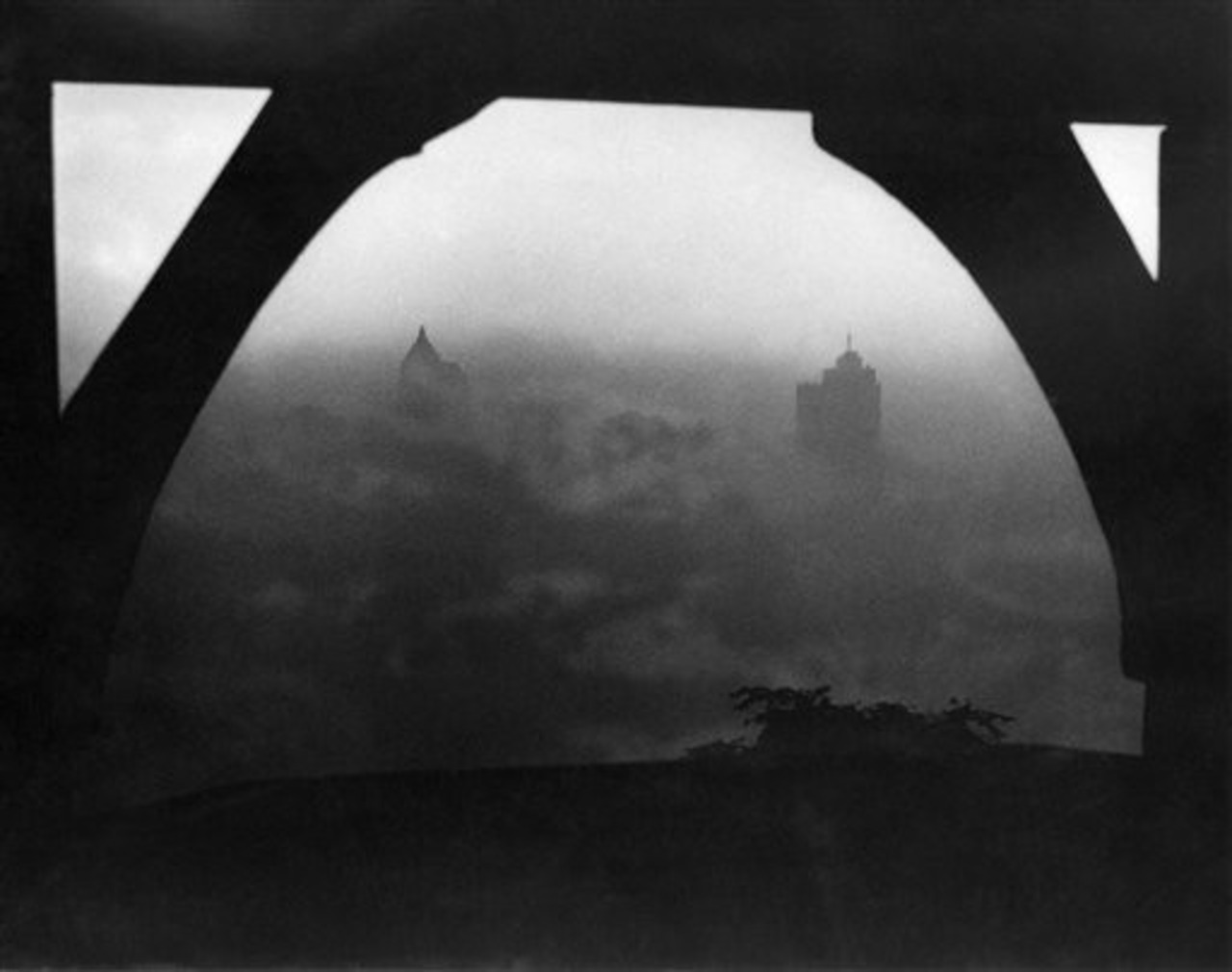

The arrival of deadly smog

At that time in Donora, the local reaction to the polluted environment was often one of indifference, as smoke was seen as a sign of economic prosperity.

However, this attitude changed dramatically in October 1948 when a weather phenomenon called a temperature inversion occurred.

On October 26, a cold front moved through Donora, leaving the air stagnant with cold air trapped below warmer air.

This “lid” effect prevented the pollutants from escaping the narrow valley, surrounded by 400-foot hills. The zinc works’ stacks, only 100 feet tall, were unable to disperse the emissions. This caused the toxic air to build up.

Reports indicated people couldn’t see their hands in front of their faces. Yet, the annual Halloween parade went on as scheduled, and the local high school football game was played.

At the time, Charles Stacey, a high school senior, recalled that the smog created a burning sensation in the throat and eyes but was considered normal for Donora.

As the smog persisted, concern grew. Residents began calling doctors with reports of respiratory distress. Due to the dense fog, first responders had to be guided by someone on foot with a flashlight.

Eventually, emergency responders had to go door-to-door, providing oxygen to residents gasping for air. The dense fog left roads impassable, so those with worsening health issues couldn’t leave town.

The first of 20 deaths occurred around 2 a.m. on October 30. Over the next 12 hours, 16 more people died.

By the end of the crisis, over 1,400 people suffered serious illnesses, and more than 4,400 experienced mild to moderate symptoms. The severe pollution also claimed the lives of 800 animals.

In total, 21 deaths from respiratory causes were documented, and it’s believed more deaths followed in the subsequent weeks due to the lasting health impacts of the smog.

Nearby hospitals filled up, and the old Donora Hotel became an improvised infirmary and morgue. The lower level of the hotel was used for the dead, while the street level accommodated the sick.

Chaos and consequences of the incident

After the smog lifted in early November, the once indifferent town of Donora was left searching for answers.

While many were hesitant to blame their employers at American Steel and Wire and Donora Zinc Works, an investigation by the United States Public Health Service (USPHS) was ordered.

This investigation became the first large-scale study of a public health crisis in U.S. history.

The lengthy investigation analyzed weather conditions and pollutant sources but failed to pinpoint a single cause.

Instead, officials identified three main factors: the pollutants from the plants, the temperature inversion, and Donora’s unique valley geography that trapped the pollutants.

A report recommended measures to prevent future incidents, including a weather alert system to warn of similar conditions.

In the aftermath, state and federal public health investigators flooded the town. Some residents, fearful of retribution from their employers, minimized their illnesses, while others were openly angry.

According to Dr. James Townsend’s 1950 account, “some residents… were more angry than afraid.”

Dozens of residents eventually filed lawsuits against the company owning the zinc works. The company defended itself by claiming the smog was an “Act of God.”

The court required autopsies for families to participate in the lawsuit, which discouraged many from participating. Eventually, the families settled for $250,000, fearing they might end up with nothing.

Dr. Townsend concluded that the smog “has shown beyond doubt that the combination of gases and particulate matter in emissions could have an adverse effect upon health.”

He recommended further research on pollution’s effects and urged industries to reduce emissions.

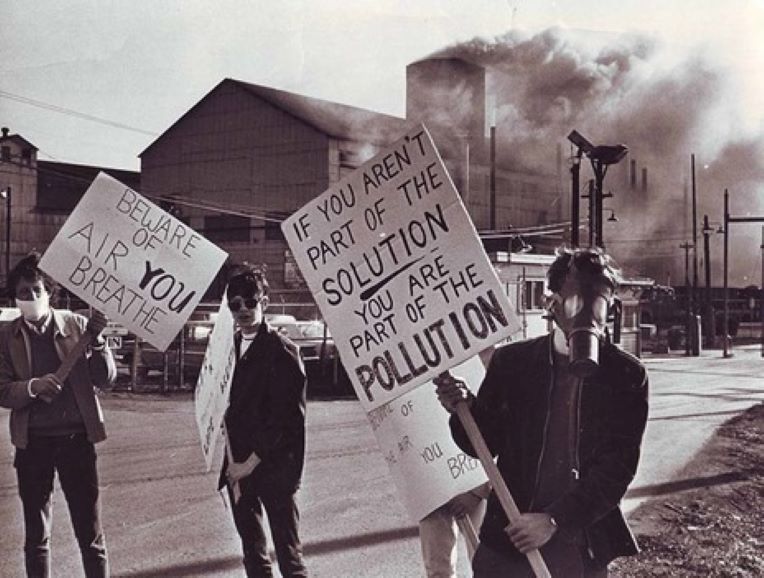

The tragic events in Donora spurred the clean air movement in the United States, leading to critical changes in environmental policies and the eventual establishment of the Clean Air Act.

In a 1999 article in Smithsonian Magazine, Marcia Spink from the EPA described Donora as a pivotal moment in recognizing the dangers of air pollution.

“Before Donora,” she said, “people thought of smog as a nuisance. It made your shirts dirty. The Donora tragedy was a wake-up call. People realized smog could kill.”

This issue wasn’t unique to Donora. The EPA’s History of Air Pollution states,

“The situation in Donora was extreme, but it reflected a trend. Air pollution had become a harsh consequence of industrial growth across the country and world. Crises like Donora’s were widely publicized; people took notice and began to act.”

Cities like Philadelphia, Boston, and Los Angeles also suffered from severe air pollution.

For example, on November 20, 1953, residents of Philadelphia, including Meriel Bush and Ruth Never, wore gas capes left over from the war to shield themselves from the eye-stinging smog and smoke that had enveloped the city for two consecutive days.

Unusual weather conditions were blamed for the haze that plagued much of the eastern United States.

The Clean Air Act of 1963

Just over a year after the Donora smog incident, President Harry S. Truman ordered the creation of a government committee to study air pollution.

This initiative marked the beginning of extensive research that eventually led to the passage of the Clean Air Act of 1963, later strengthened by the Clean Air Act of 1970.

By the time these laws were enacted, the Donora zinc works had already closed in 1957.

According to volunteer curator and researcher Brian Charlton, many locals believed the plant’s closure in 1957 was due to the negative attention it received after the smog incident.

However, the reality was that a more efficient process developed by an English company rendered Donora’s smelters obsolete, leading to the plant’s closure.

The shutdown of the zinc works, followed by the nearby steel mill a decade later, initiated a gradual economic decline in Donora that persists today.

Donora’s residents take pride in their town’s crucial role in environmental history.

“One of our tag lines is ‘Clean Air Started Here,'” Charlton says. “Everyone looks to us as the ground zero of the environmental movement, of making sure that industry doesn’t get out of control.”