Anne Frank, a name etched into history through her poignant diary, “The Diary of a Young Girl,” becomes a profound symbol of strength in difficult times.

Her diary shares her thoughts and feelings as a young girl facing the challenges of war. It gives a personal look at how she and her family lived in hiding, showing both the ordinary moments and the difficulties they faced.

What did the girl have to go through while writing that diary? Let’s dive deeper into this article to find out more.

What disrupted the life of Anne’s family

Anne Frank was born in 1929 in Frankfurt, Germany, to Edith and Otto Frank, who loved and encouraged reading. She had an older sister, Margot, who was three years older than her.

During this time, Germany faced significant unemployment and poverty, alongside the rising influence of Adolf Hitler and his anti-Semitic ideology. Hitler blamed Jews for the country’s problems, tapping into widespread anti-Jewish sentiments.

Due to these conditions, Anne’s parents, Otto and Edith Frank, chose to move to Amsterdam. There, Otto established a business trading in pectin, a key ingredient used in making jams.

How her life in the Netherlands was

Anne quickly settled into life in the Netherlands, learning the language, making friends, and attending a local Dutch school. Her father faced challenges in getting his business going, while Otto’s plans for a company in England didn’t work out. However, things improved when he began selling herbs and spices alongside pectin.

Then, on September 1, 1939, when Anne turned 10, Nazi Germany invaded Poland, sparking World War II. Soon after, on May 10, 1940, the Nazis invaded the Netherlands. Within days, the Dutch army surrendered, and life changed drastically. The Nazis imposed increasingly harsh laws targeting Jews, restricting them from parks, cinemas, and non-Jewish stores.

These rules closed off more and more of Anne’s world. Her father lost his business because Jews were barred from owning companies, and Anne, like other Jewish children, had to attend separate schools.

Anne wrote a Diary about the two years in hiding

When the Nazis escalated their actions, rumors spread that all Jews might be forced out of the Netherlands.

On July 5, 1942, Margot got a summons to report for what the Nazis called a ‘labor camp’ in Germany. Her parents, sensing danger, didn’t buy it and decided to go into hiding the very next day to escape persecution.

Earlier that spring in 1942, Anne’s father had been setting up a hiding spot in the back of his business at Prinsengracht 263. He had help from his former coworkers, all knowing they faced death if caught sheltering Jews.

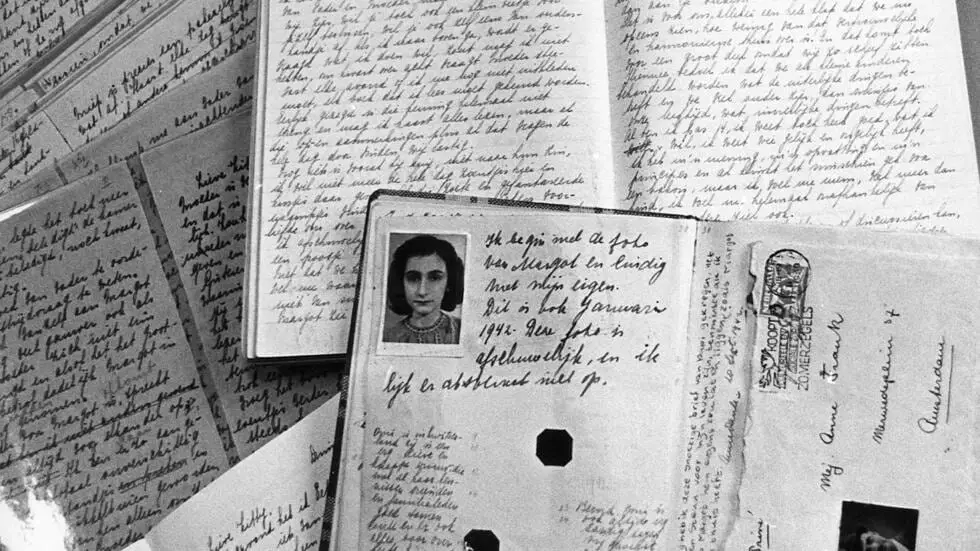

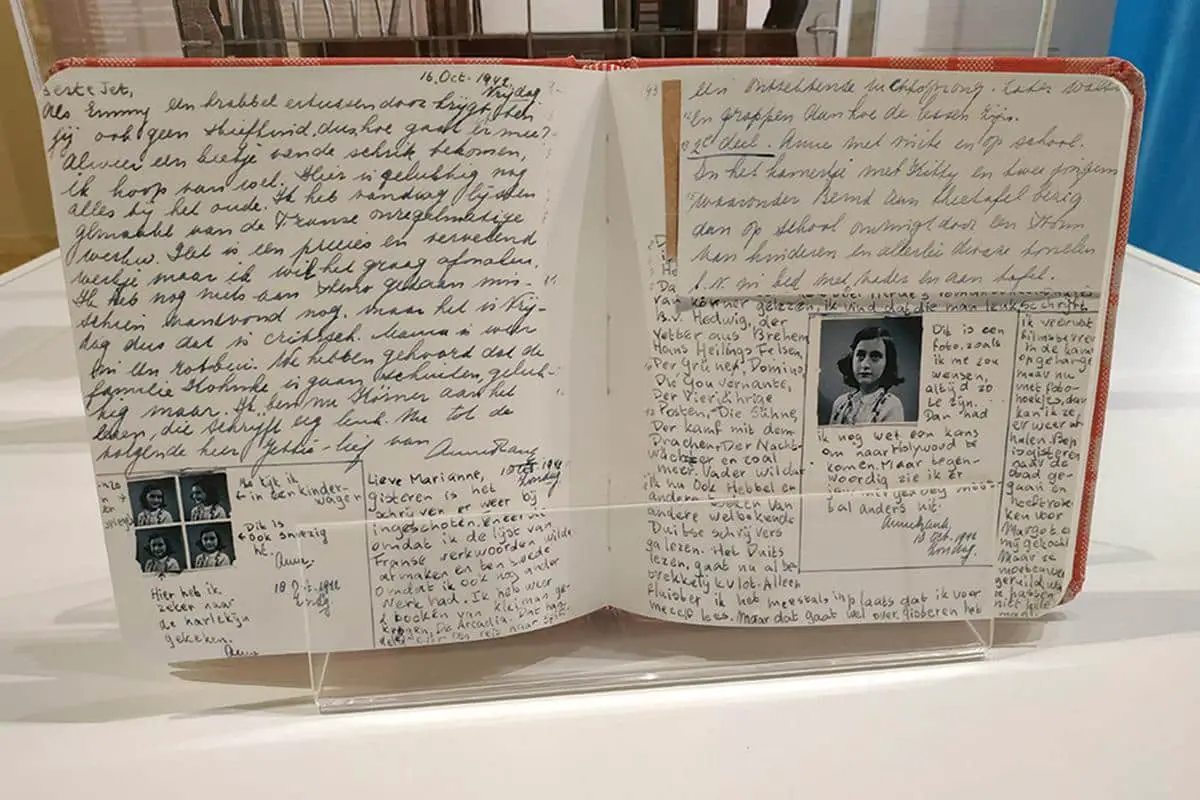

Just before going into hiding on her thirteenth birthday, Anne received a diary. During the two years in hiding, Anne wrote about life in the Secret Annex, pouring out her emotions and thoughts.

She also penned short stories, began a novel, and copied passages from books she read into her Book of Beautiful Sentences. Writing became her refuge, helping her endure the passage of time.

When the Dutch Minister of Education in England made a plea on Radio Orange to safeguard war diaries and documents, Anne Frank was moved to combine her personal diaries into a single narrative titled “Het Achterhuis” (The Secret Annex).

On April 5, 1944, Anne, who aspired to become a journalist, wrote in her diary:

“I finally realized that I must do my schoolwork to keep from being ignorant, to get on in life, to become a journalist, because that’s what I want! I know I can write …, but it remains to be seen whether I really have talent …

And if I don’t have the talent to write books or newspaper articles, I can always write for myself. But I want to achieve more than that. I can’t imagine living like Mother, Mrs. van Daan and all the women who go about their work and are then forgotten. I need to have something besides a husband and children to devote myself to! …”

Despite being discovered and arrested by police on August 4, 1944, parts of Anne’s writings were saved. Two helpers managed to take the documents before the Secret Annex was cleared out under Nazi orders.

They were taken to the Westerbork transit camp, where over 100,000 Jews, mainly Dutch and German, had passed through. On September 3, 1944, they were deported from Westerbork to Auschwitz, the final destination of their journey after three days.

Fate of Anne and her family

Upon arriving at Auschwitz, SS, a major paramilitary organization under Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party in Nazi Germany, immediately separated men from women and children. Otto Frank was separated from his family during this brutal process.

Those considered fit for work were allowed to stay, while the rest, including 549 out of 1,019 passengers (all children under 15), were sent straight to the gas chambers. Anne Frank, just 15 years old at the time, narrowly avoided this fate.

In the midst of unimaginable horrors, Anne underwent dehumanizing rituals: forced nudity for disinfection, head shaved, and a tattooed number on her arm. Days meant grueling labor like hauling rocks and digging sod; nights brought overcrowded barracks.

Witness accounts varied: some saw her anguish at children led to gas chambers; others praised her resilience, obtaining extra bread rations for her mother, sister, and herself.

Disease spread quickly; scabies infected her skin. Eventually, she and her sister were moved to a dark, rat-infested infirmary. Edith Frank, sacrificing her own meals, fed her daughters through a hole in the wall, her act of love in a place of unspeakable suffering.

On 28 October, selections began at Bergen-Belsen, where over 8,000 women, including Anne and Margot Frank, were chosen for relocation. Unfortunately, Edith Frank left behind and tragically succumbed to illness, starvation, and exhaustion.

During that time, a typhus outbreak swept through the camp, claiming the lives of 17,000 prisoners. Turgel, who worked in the camp hospital, described the devastating impact: “[The] shock of seeing her in this emaciated state was indescribable.”

At that time, a typhus epidemic spread through the camp, killing 17,000 prisoners. Turgel, who worked in the camp hospital, said that the epidemic took a terrible toll on the inmates: “The people were dying like flies—in the hundreds. Reports used to come in—500 people who died. Three hundred? We said, ‘Thank God, only 300.'”

It’s reported that Margot, in a weakened state, fell from her bunk and died from the shock. Anne passed away just a day after Margot.

Anne’s father’s emotions upon discovering the existence of the diary

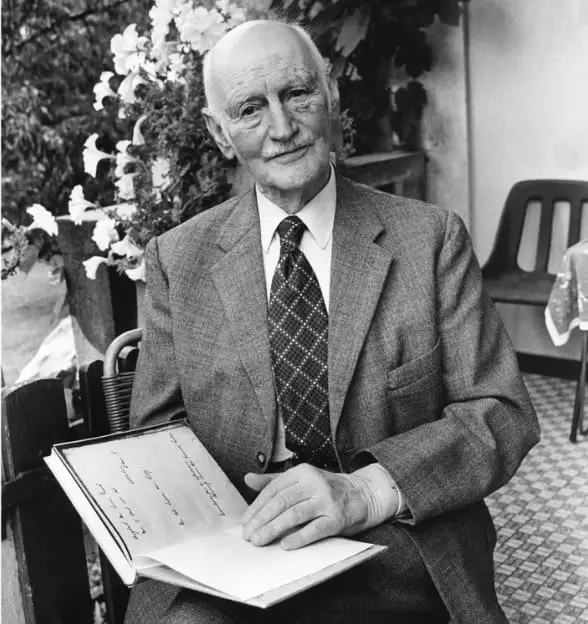

Anne Frank’s father, Otto, was a survivor among those who hid in the Secret Annex during the war. Liberated from Auschwitz by the Russians, Otto went back to the Netherlands, only to learn along the way that his wife, Edith, had passed away. His heartache deepened upon discovering that his daughters, Anne and Margot, also did not survive. In 1945, he was given Anne’s notebooks.

Otto Frank later shared that he had no idea Anne wrote what happened during their time in hiding. He was deeply moved when reading the diary. It was the first time he saw Anne’s private side and encountered sections of the diary she hadn’t shared with anyone else.

He said, “For me it was a revelation… I had no idea of the depth of her thoughts and feelings… She had kept all these feelings to herself.”

Anne’s diary becomes world famous

Anne Frank intended her diary to be a private outlet for her thoughts. She candidly depicted her life, family, companions, and their circumstances, while also revealing her aspirations to become a published fiction writer.

Moved by her dream, Otto Frank gave the diary to historian Annie Romein-Verschoor. Then, she passed it to her husband Jan Romein, who wrote an article titled “Kinderstem” (“A Child’s Voice”), published in Het Parool on April 3, 1946.

In his piece, he described the diary as speaking in a child’s voice, encapsulating the horrors of fascism more powerfully than the evidence at Nuremberg.

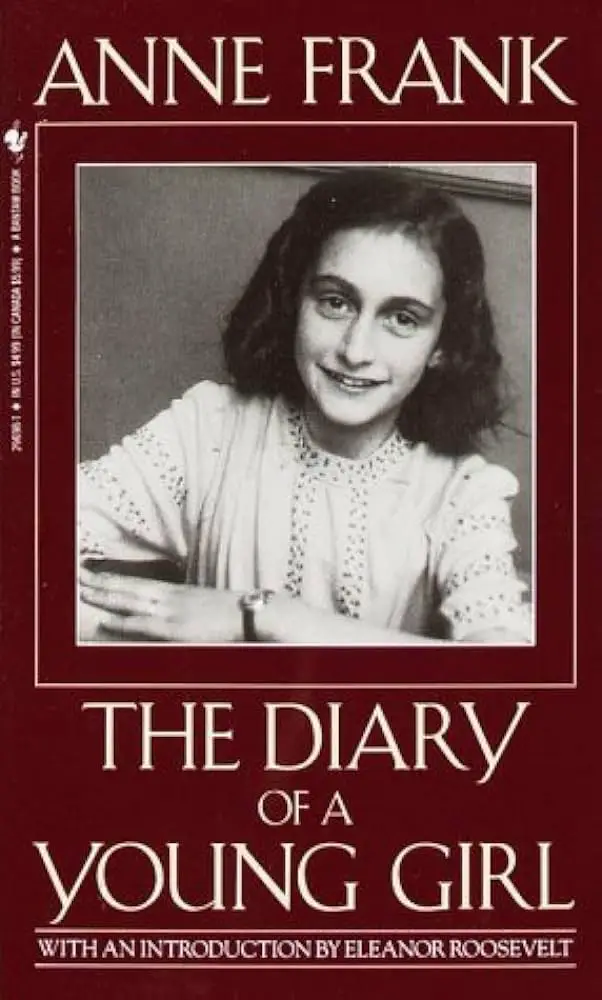

This article garnered huge attention from publishers, leading to the diary’s publication in the Netherlands as “Het Achterhuis” (The Annex) in 1947, followed by five additional printings by 1950.

First published in Germany and France in 1950, Anne Frank’s diary faced initial rejections before finding success with its 1952 release in the United Kingdom. The American edition, titled Anne Frank: The Diary of a Young Girl, received positive reviews upon its publication the same year.

While it was successful in France, Germany, and the US, it struggled to find an audience in the UK and went out of print by 1953.

Remarkably, the diary gained significant popularity in Japan, selling over 100,000 copies in its first edition and cementing Anne Frank as a poignant symbol of wartime youth.

The diary’s impact expanded further with a successful play adaptation by Frances Goodrich and Albert Hackett premiering in New York City in 1955, which later earned a Pulitzer Prize for Drama. This was followed by the acclaimed 1959 film adaptation, solidifying Anne’s story in both critical acclaim and commercial success.

Over time, Anne Frank’s diary became increasingly popular, especially in American schools where it became a part of the curriculum, introducing her story to new generations of readers.