In the past, it wasn’t uncommon for soldiers to join the military at a very young age. But not everyone could maintain a positive attitude. Elgin Staples became a sailor in Akron at the age of 19 and was willing to die for his country.

He later wrote, “War isn’t so bad and there’s still plenty to eat.” During the war, he faced death, but luck smiled upon him when he miraculously survived.

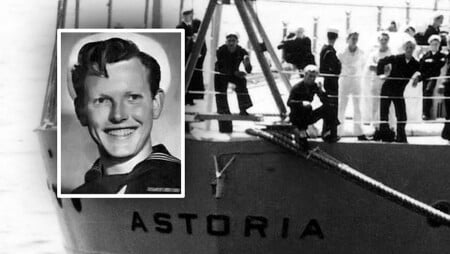

Elgin Staples served aboard the USS Astoria

Nineteen-year-old Elgin Staples, a signalman third class from Akron, enlisted in the U.S. Navy in May 1941 after his junior year at South High School. He trained at Pearl Harbor and set sail aboard the cruiser USS Astoria on December 5, just two days before the Japanese attack.

While the ship evacuated Americans from Wake Island, Midway, and Guam, Staples tried to stay positive. He mused “The water out there is clear and blue and the sunsets at Midway are the most beautiful in the world.”

Staples joined USS Astoria’s battles

The USS Astoria had been through battles in the Coral Sea and at Midway. Staples spoke of the war in a calm manner, like he was talking about a baseball game at Akron’s League Park.

“When the thing finally happens and the battle is upon you — first, you see the planes a long way off,” he said. “Then our fighters get into action and you have a feeling of great pride when you see the enemy planes go down like balls of fire in the distance. You feel like cheering and sometimes you do cheer.”

“The little specks of planes grow bigger and bigger and fewer and fewer. When they finally are above you, you are so busy passing ammunition and manning guns that even when your best buddies fall all around you, you don’t have time to be afraid. You just go right on working. Afterwards, well, afterwards, is when you begin to feel it.”

In August, the Astoria sailed to the Solomon Islands to support the Marines landing on Guadalcanal Island. Late one night, after midnight on August 8, Japanese shells hit the cruiser, turning the darkness into fiery chaos.

Staples quickly put on his inflatable life belt and rushed to the deck. But another explosion shook the ship, causing him to lose his balance and fall 30 feet into the dark ocean with shrapnel wounds to his leg and shoulder.

“I began treading water, trying to stay calm as I felt things brushing against my legs, knowing that if a shark attacked me, any moment could be my last,” he later wrote. “And the sharks weren’t the only danger: The powerful current threatened to sweep me out to sea.”

Staples floated in the dark for four hours until a U.S. destroyer rescued him at dawn and brought him back to the damaged USS Astoria. Despite the sailors’ efforts to repair the ship, it eventually sank, forcing the crew to abandon it.

Still wearing his life belt, Staples jumped into the Pacific Ocean and was rescued by another U.S. ship. Over 200 men were lost aboard the Astoria during the Battle of Savo Island.

Staples kept the khaki life belt as a memento and was surprised to see the Firestone Tire & Rubber Co. logo on it. How about that? His hometown company had saved his life.

Go back home

The sailor returned to Akron to heal from his wounds and had an emotional reunion with his mother, Vera Mueller-Staples, at her West Market Street home. In the book “Chicken Soup for the Veteran’s Soul”, originally published 2001, he wrote:

“After a quietly emotional welcome, I sat with my mother in our kitchen, telling her about my recent ordeal and hearing what had happened at home since I had gone away. My mother informed me that “to do her part,” she had gotten a wartime job at the Firestone plant. Surprised, I jumped up and grabbing my life belt from my duffel bag, put it on the table in front of her.”

“Take a look at that, Mom,” I said, “It was made right here in Akron, at your plant.”

“She leaned forward and taking the rubber belt in her hands, she read the label. She had just heard the story and knew that in the darkness of that terrible night, it was this one piece of rubber that had saved my life.

When she looked up at me, her mouth and her eyes were open wide with surprise. “Son, I’m an inspector at Firestone. This is my inspector number,” she said, her voice hardly above a whisper.

“We stared at each other, too stunned to speak. Then I stood up, walked around the table and pulled her up from her chair. We held each other in a tight embrace, saying nothing. My mother was not a demonstrative woman, but the significance of this amazing coincidence overcame her usual reserve. We hugged each other for a long, long time, feeling the bond between us. My mother had put her arms halfway around the world to save me.”

Their miraculous story caught the attention of the Akron Beacon Journal and soon after, they were invited to appear on the CBS radio program We the People on October 18, 1942. On the show, Staples and his mother emphasized the importance of supporting the war effort both on the battlefield and at home.

Mueller stated, “There are millions of women whose sons are in the fighting forces right now. We’ve got to help them come back. And the best way is to get into war work.”

Two days later, Staples spoke at a luncheon in Akron with Firestone executives. He said, “We are all in this fight together and if we are going to win, we must all work together for the final victory.”

Staples returned to active duty that same month. In December 1942, his mother Vera was honored by the War Congress of American Industry in New York for her “initiative, skill and constructive aid” in industry. Both survived the war and were reunited afterward.