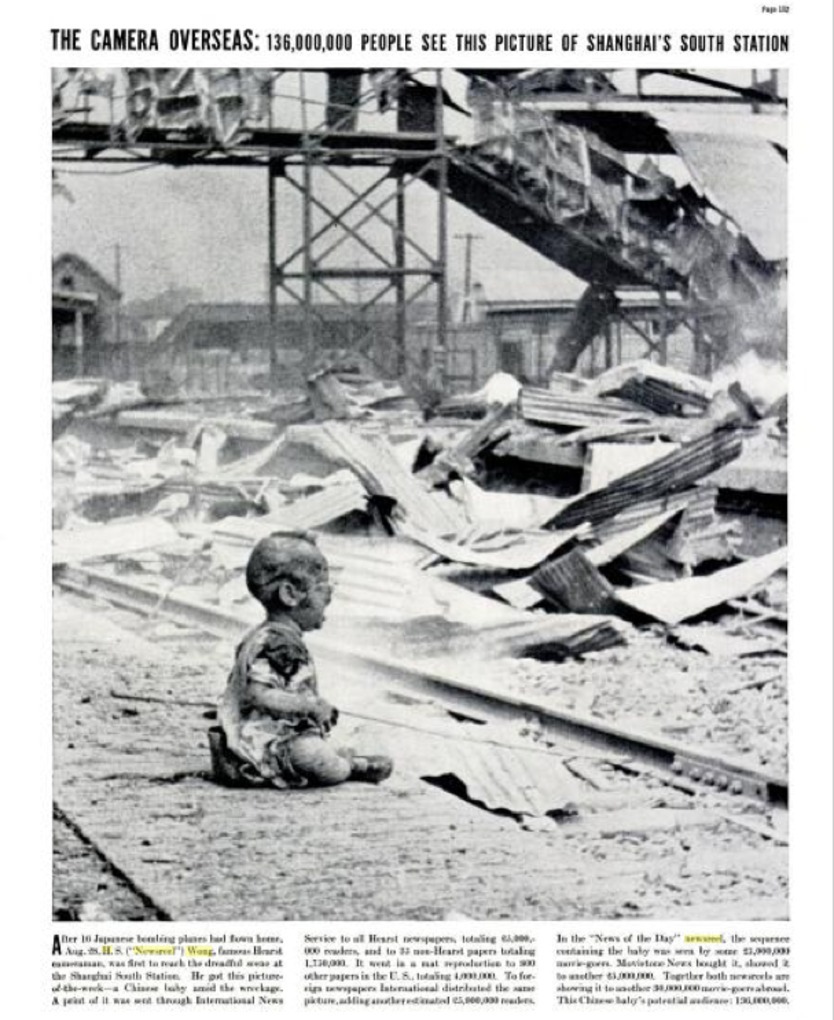

“Bloody Saturday” by H. S. Wong– The haunting photograph of a Chinese baby crying amidst the bombed-out ruins of Shanghai South Railway Station became a powerful symbol of Japanese wartime cruelty in China.

This touching image vividly captured the devastating effects of the 1930s war. Journalist Harold Isaacs praised it as “one of the most successful propaganda pieces of all time.”

However, the famous still image is rarely referred to by name. It has been called Motherless Chinese Baby, Chinese Baby, and The Baby in the Shanghai Railroad Station, each title emphasizing the tragic innocence caught in the horrors of war.

The story behind the photo

During the Battle of Shanghai, part of the Second Sino-Japanese War, Japanese forces launched a devastating attack on Shanghai, China’s most populous city.

On August 14, 1937, known as “Bloody Saturday,” three Japanese aircraft bombed two major hotels on Nanking Road, leaving behind a trail of destruction that was captured by newsreel photographers like Wong, Harrison Forman, and George Krainukov.

Wong, a Chinese cameraman who owned a camera shop in Shanghai, was among those who documented the gruesome aftermath of the attack.

As the National Revolutionary Army began to retreat, leaving a blockade across the Huangpu River, an international group of journalists gathered to document the expected bombing of the blockade.

They waited atop the Butterfield & Swire building, but by 3 p.m., when no aircraft appeared, most of the reporters left.

Wong, however, remained. At 4 p.m., 16 Japanese planes suddenly appeared, not to bomb the blockade but to target Shanghai’s South Station, where war refugees were waiting for a train to Hangzhou.

Wong quickly made his way to the railway station. The sight that greeted him was horrifying—bodies were strewn across the tracks, limbs scattered everywhere, and the air was thick with smoke and the smell of burning flesh.

Wong documented the devastation with his Eyemo newsreel camera while also capturing several poignant still photographs with his Leica.

Amidst the chaos, Wong forced himself to focus on his work to cope with the overwhelming horror around him. At one chilling moment, he realized that “his shoes were soaked with blood.”

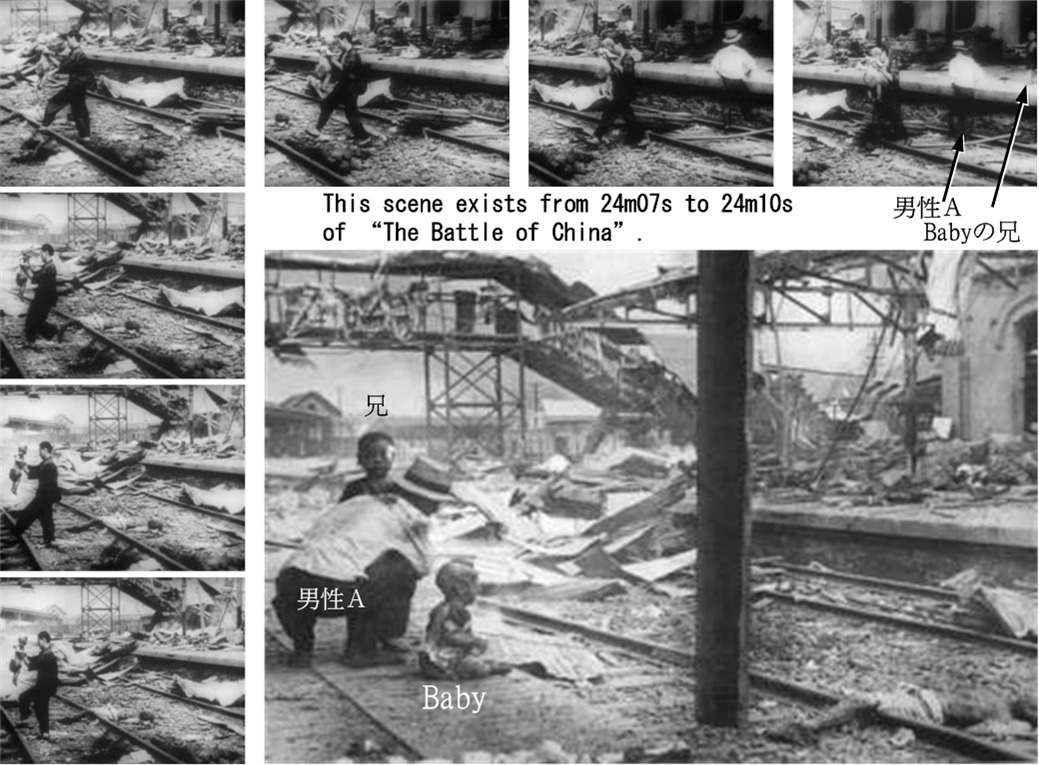

As he continued filming, his lens caught sight of a man frantically attempting to rescue two injured children from the railway tracks, their mother lying lifeless nearby. Wong seized these heart-wrenching moments, even as Japanese bombers returned overhead.

Wong never learned the identity of the baby he filmed or whether the child survived. The following day, he developed the film and showed the images to a colleague, Malcolm Rosholt, exclaiming, “Look at this one!”

Reports soon emerged that around 1,800 people, mostly women and children, had been at the station, with fewer than 300 surviving the attack.

Wong’s footage captured the heart-wrenching reality of civilian suffering during the Battle of Shanghai.

When the photo was released

Wong’s harrowing newsreel footage was quickly sent from Shanghai to Manila on a U.S. Navy ship. From there, it was flown aboard a Pan American World Airways airliner to New York City.

By mid-September 1937, the footage began screening in movie theaters, reaching an estimated 50 million viewers in the United States and another 30 million internationally within a month.

The still image of the crying baby, taken from the footage, was widely circulated by Hearst Corporation newspapers and affiliates.

An additional 1.75 million copies appeared in non-Hearst U.S. newspapers, with 4 million more people seeing it in other publications. Globally, the image reached 25 million viewers.

The photograph made its first appearance in Life magazine on October 4, 1937. By then, it was estimated that 136 million people had seen the image.

How people responded

The “unforgettable” image of the crying baby in the ruins of Shanghai became one of the most powerful photographs to fuel anti-Japanese feelings in the United States.

The photo sparked a “tidal wave of sympathy” from Americans for China, and it was widely shared to encourage donations for Chinese relief efforts.

It also led to international protests. The United States, the United Kingdom, and France all condemned Japan for bombing Chinese civilians, using the image as a strong symbol to rally around.

Senator George W. Norris, long a proponent of isolationism and non-intervention, was deeply moved by the image. He condemned the Japanese actions as “disgraceful, ignoble, barbarous, and cruel, even beyond the power of language to describe.”

The American public responded with outrage, using terms like “butchers” and “murderers” to describe the Japanese military.

The photograph even reached the ears of Japanese officials. After Shanghai’s surrender, IJN Admiral Kōichi Shiozawa remarked to a reporter from The New York Times at a cocktail party, “I see your American newspapers have nicknamed me the Babykiller.”

The image was voted by Life magazine readers as one of the top ten “Pictures of the Year” for 1937. In 1944, Wong’s newsreel footage was featured in Frank Capra’s film The Battle of China, part of the Why We Fight series as a symbol of the horrors of war.

Allegations of falsehood

At the time, Japanese nationalists claimed that Wong’s photograph was a fake, and the Japanese government placed a $50,000 bounty on his head—equivalent to over a million dollars today.

Wong was known for his opposition to the Japanese invasion of China and had leftist political sympathies. He worked for William Randolph Hearst, who famously told his newsmen during the Spanish-American War, “You furnish the pictures and I’ll furnish the war.”

Controversy deepened when another of Wong’s photos appeared in Look magazine in December 1937, showing a man near the crying baby bent over a child. Some alleged that this man was Wong’s assistant, staging the scene for a more dramatic effect.

Others, including Wong himself, described the man as the father of the children, attempting to rescue them as Japanese planes returned.

Japanese propagandists used these claims to discredit the photo and broader reports of Japanese atrocities in Shanghai.

In 1956, Look magazine’s Arthur Rothstein supported the idea that Wong had staged the photograph, but in 1975, Life magazine featured the image in a picture book, dismissing the staging claims as fabricated rumors.

The debate resurfaced in 1999 when a nationalist group in Japan, led by Fujioka Nobukatsu, argued that Wong manipulated the scene to create a “pitiable sight” for American audiences, even accusing him of adding smoke to enhance the drama.

However, witnesses like Malcolm Rosholt confirmed that the station was still smoking when Wong arrived.

Despite the controversy, Wong continued his work, filming more newsreels of Japanese attacks in China, including the Battle of Xuzhou and bombings in Guangzhou.

Although he operated under British protection, ongoing death threats from Japanese nationalists eventually forced him to relocate to Hong Kong with his family for safety.

The photo’s powerful impact

In the late 1940s, while in art school, Andy Warhol created a painting version of the photograph, marking the start of his journey in turning photos into art.

Though this early work is lost, it set the stage for his later “Disaster Series” in the 1960s, where he explored powerful photojournalistic images.

The crying baby photograph had such a strong impact that, in 1977, journalist Lowell Thomas compared it to iconic World War II images like the tearful French man and Joe Rosenthal’s “Raising the Flag on Iwo Jima.”

H.S. Wong, the photographer behind the image, retired to Taipei in the 1970s and passed away at 81 in 1981. He was honored in 2010 by the Asian American Journalists Association for his pioneering work.

The influence of Wong’s photograph persisted into the 21st century. In 2000, artist Miao Xiaochun projected the image faintly against a white curtain to symbolize its fading impact.

The photo was featured in the Time-Life book “100 Photographs that Changed the World” (2003) and National Geographic’s “Concise History of the World” (2006). National Geographic’s Michael S. Sweeney called it a “harbinger of Eastern militarism.”