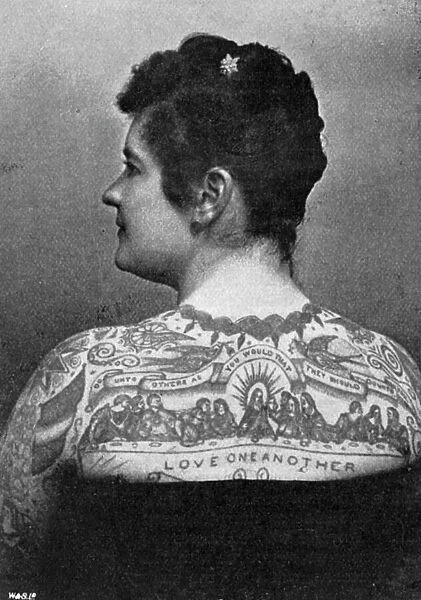

At the turn of the 20th century, when tattoos were considered taboo, Maud Wagner broke barriers by both giving and receiving hundreds of tattoos. She not only married a tattoo artist but also covered her body in ink — just like him.

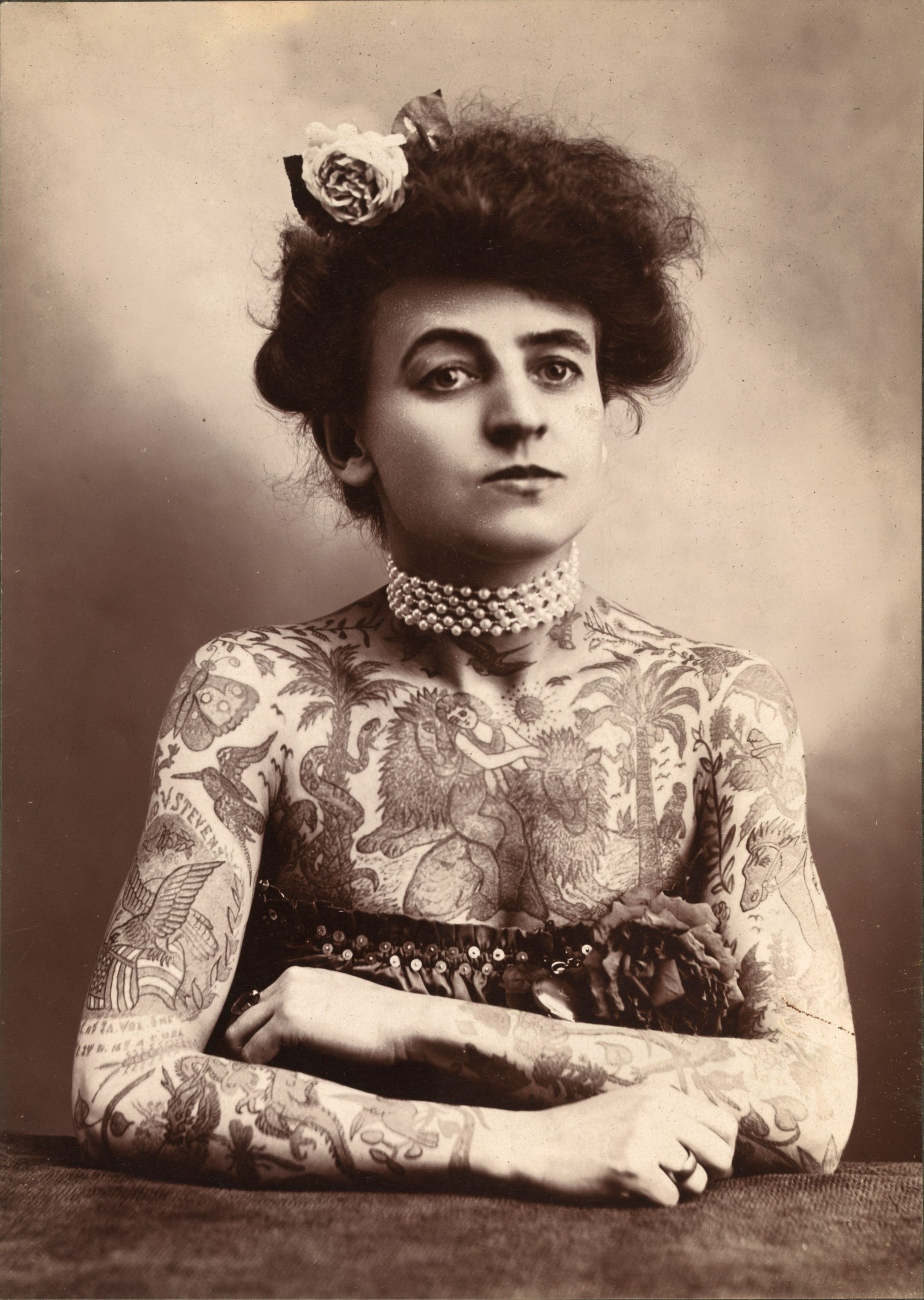

Her pale skin transformed into a vibrant canvas with colorful images of lions, butterflies, and trees. Stunning designs spread across her chest, up to her collarbone, and all over her arms.

Maud Wagner was more than just a canvas for others’ art. She learned the intricate “hokey-pokey” tattooing method from her husband and began creating artistic designs of her own.

Her skill made her the first female tattoo artist in the United States — as well as an emblem of self-determination when women had few rights.

How Maud Wagner fell in love with the needle

Maud Wagner, born Maud Stevens on February 12, 1877, in Emporia, Kansas, was the daughter of David Van Buran Stevens and Sarah Jane McGee. Not much is known about her early years, but she eventually joined the world of traveling circuses as an aerialist and contortionist.

In her youth, tattoos were not commonly seen, especially among women. However, by the end of the 19th century, tattoos had become a hidden trend among the upper class. Notably, Winston Churchill’s mother had a tattoo of a snake eating its tail.

By 1897, it was estimated that 75 percent of American society women had tattoos. These tattoos were small and easily concealed under the era’s long sleeves and high collars.

However, this trend was fading by the 1920s, with tattoos being considered suitable only “for an illiterate seaman but hardly for an aristocrat,” as one socialite put it.

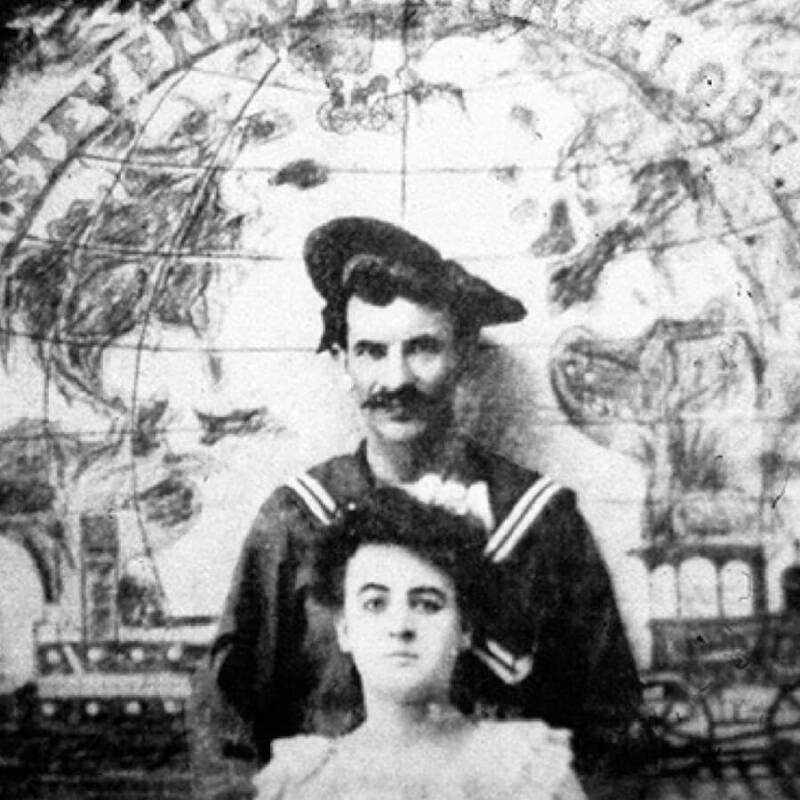

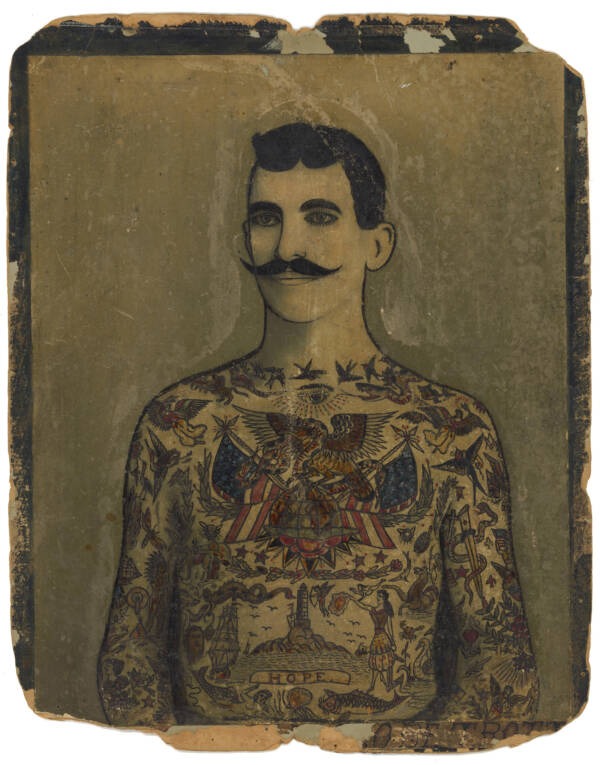

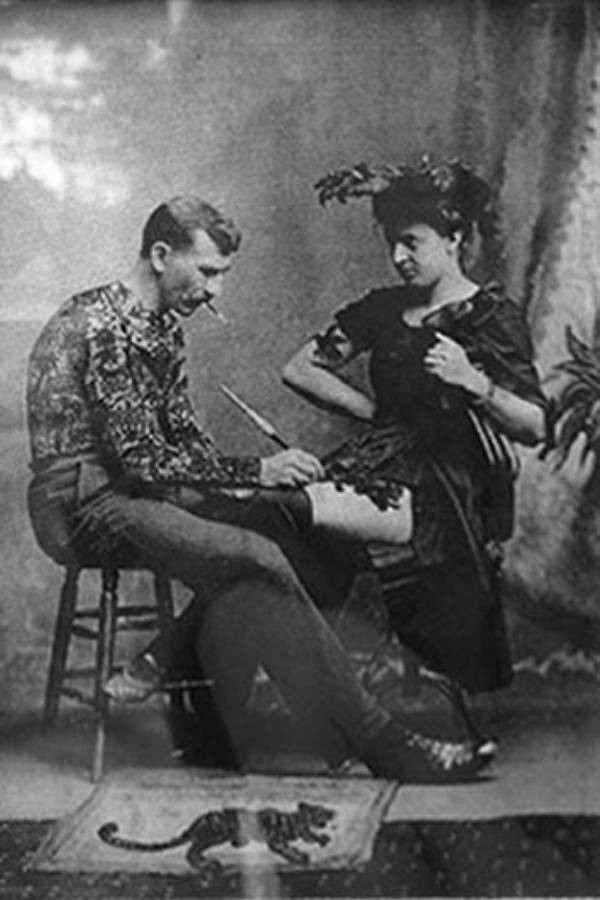

Maud’s life took a pivotal turn in 1904 at the Louisiana Purchase Exposition, also known as the St. Louis World’s Fair. There, she met August “Gus” Wagner, a man covered in nearly 300 tattoos who claimed to be the “most artistically marked-up man in America.”

Gus boasted, “I’ve got a history of my life on my breast, a history of America on my back, a romance with the sea on each arm, the history of Japan on one leg, and the history of China on the other.”

He fascinated Maud with tales of his adventures and how he learned hand-tattooing techniques from tribes in Java and Borneo. Despite the invention of the electric tattoo machine by Samuel O’Reilly in 1891, Gus preferred the traditional stick-and-poke method.

Intrigued by Gus and his stories, Maud made a deal with him: she would go on a date with him if he taught her how to tattoo. This agreement led to her falling in love with both the art of tattooing and Gus himself.

They married on October 3, 1904, and soon after, they welcomed a daughter named Lotteva. Maud then began developing her own collection of tattoos, marking the beginning of her career as America’s first female tattoo artist.

She defied social norms and became a tattoo legend

Maud Wagner’s tattoos reflected the popular designs of her time, featuring patriotic themes and animals like monkeys, snakes, and horses. She even had her own name inked on her left arm. However, there was nothing typical about Maud herself.

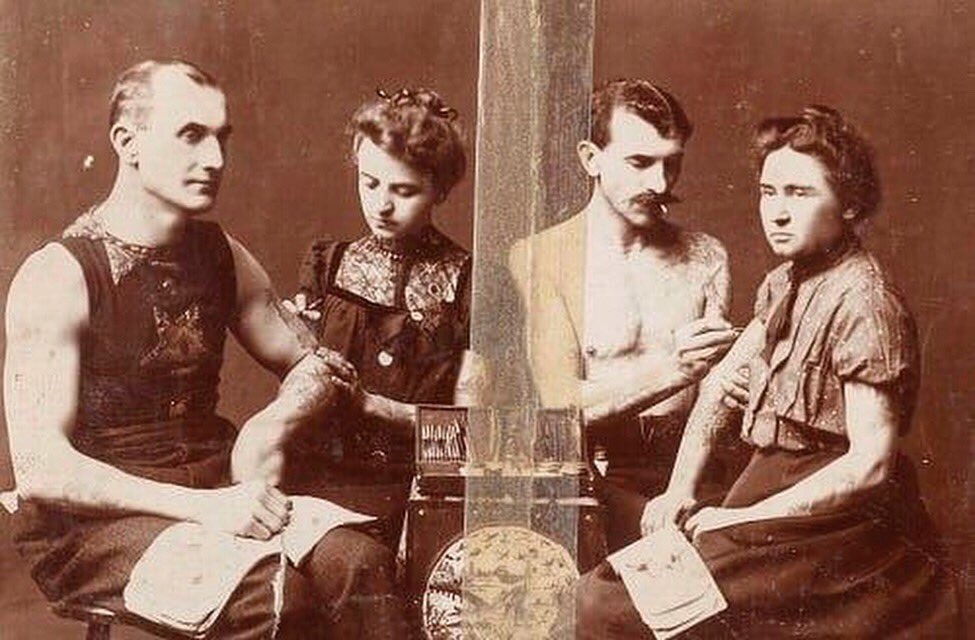

She and her husband, Gus Wagner, were heavily tattooed and became popular attractions in the circus world. They could earn up to $200 a week (about $2,000 today) by publicly displaying their tattoos.

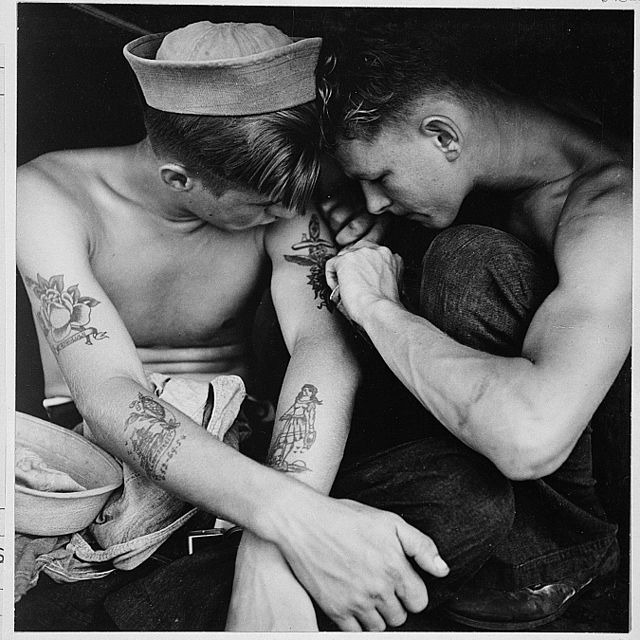

Tattoo popularity had waned by the early 20th century. Newspapers warned that tattoos could spread diseases, and tattoo artists were hard to find. By 1936, only 6 percent of Americans had tattoos, according to LIFE Magazine.

Still, Gus and Maud Wagner continued to tattoo. They tattooed their circus colleagues and curious onlookers, inking as many as 1,900 people over a few months.

Their daughter Lotteva recalled in an interview with the Dallas Morning News that most customers wanted tattoos of their pet dogs, cats, lovers’ hearts, butterflies, and birds. “How they do love birds,” she added.

Their tattoo work was so lucrative that “my father probably earned as much as a bank president at the fair,” Lotteva said.

The Wagners worked in vaudeville houses, penny arcades, county fairs, and Wild West shows as tattooists and tattooed attractions. Maud became the first female tattoo artist in the United States to work alongside Gus.

Thanks to the conservative clothing of the early 20th century, they could blend in when they wanted to. Even so, their neighbors in Kansas told stories about the “circus freaks” next door to scare their children.

Gus died in 1941 after being struck by lightning, and Maud passed away in 1961. Their daughter, Lotteva, carried on the family tradition of tattooing others, though she never got tattoos herself because Maud had forbidden Gus from tattooing their daughter.

“Mama wouldn’t let Papa tattoo me,” Lotteva said. “I never understood why. She relented after he died and said I could get tattoos then, but I said that if Papa couldn’t do them like he had done hers, then nobody would.”

Her legacy lives on

Maud Wagner would have been a striking figure in her time, but today, she might blend into the streets of Los Angeles or Brooklyn without raising an eyebrow. Yet, she broke some important barriers in the early 20th century.

Not only did she become the first female tattoo artist in the United States, but she also covered her own skin with tattoos, taking ownership of her body at a time when American women couldn’t even vote.

In this way, Maud Wagner is part of a more significant trend involving women and tattoos. American women in modern times are actually more likely than men to have ink (23 percent versus 19 percent, according to a 2012 poll). And there may be a reason for that.

In the book Bodies of Subversion: A Secret History of Women and Tattoos, Margot Mifflin argues that feminism and tattoos are linked.

“Tattoos appeal to contemporary women both as emblems of empowerment [and] self-determination,” Mifflin wrote. Especially at a time “when controversies about abortion rights, date rape, and sexual harassment have made [women] think hard about who controls their bodies — and why.”

Women today have also used tattoos as a way to regain control over their bodies after mastectomies.

In some cases, they can actually bill their insurance companies for such tattoos. Since Wagner was a trailblazer in the world of tattoos, she helped pave the way for modern women to take these leaps.