The Industrial Revolution saw rapid growth, and coal was key. It powered factories, railways, and ships, driving economic progress but at a high human cost.

After World War II, labor needs changed. Many people moved to find work, especially in mining and steel. Belgium’s growing industries needed workers, and many Italians migrated there, facing harsh and dangerous conditions.

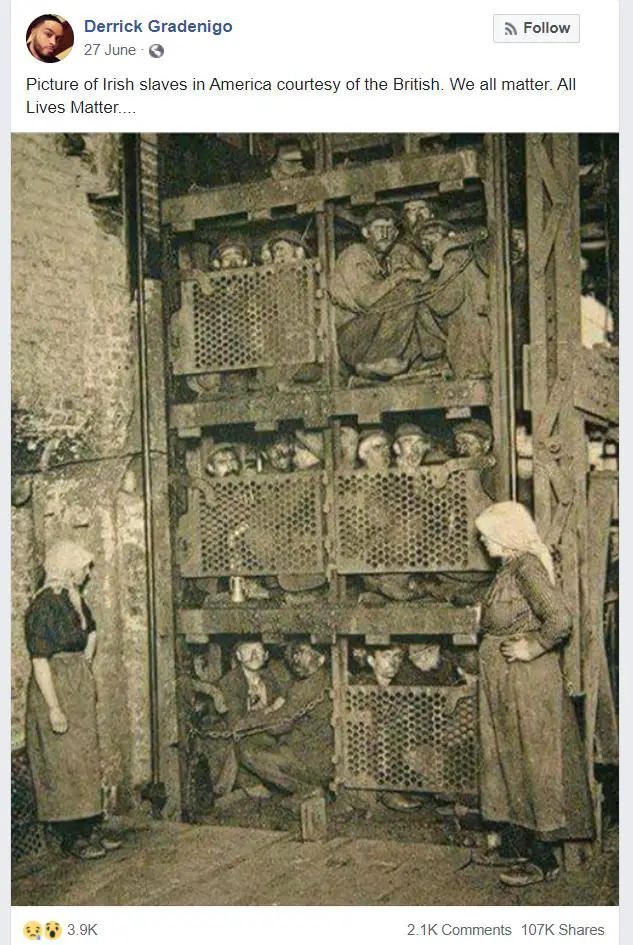

Among historical photographs capturing the cramped, risky daily life of these miners, the one below is perhaps the most widely shared.

The image of coal miners in an elevator, early 20th century

A picture of men stiflingly packed inside a mining elevator has gone viral on the internet with various contradictions, often influenced by political narratives.

One notable instance is a Facebook post claiming the photograph depicts “Irish slaves in America.” This post, which was shared hundreds of thousands of times, was removed by Facebook for presenting a false historical narrative.

So, what is the truth behind this image?

This image often shared with misleading captions, actually depicts Italian migrant workers in Belgium during the post-World War II period. These workers played a crucial role in the development of Belgium’s mining and steel industries.

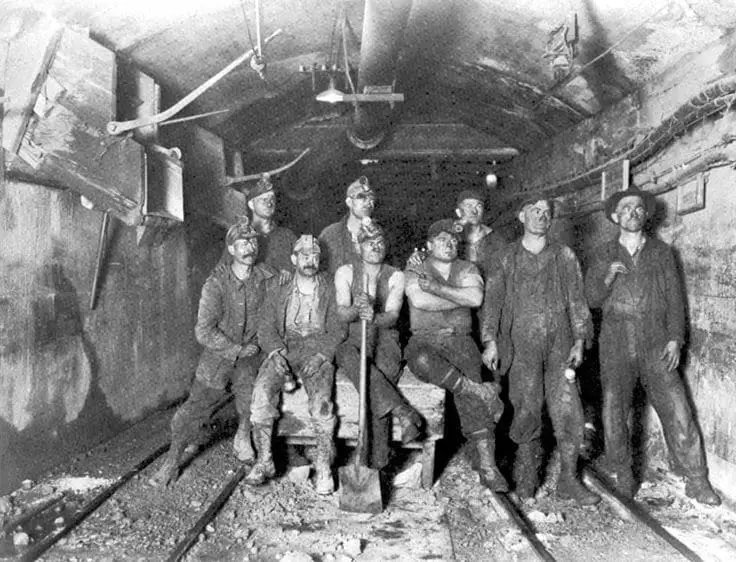

After World War II, there was a significant demand for labor in Belgium’s burgeoning industrial sectors. Many Italians migrated to Belgium to fill these positions, working under harsh and dangerous conditions.

This image highlights the cramped and dangerous nature of their daily commute within the mines.

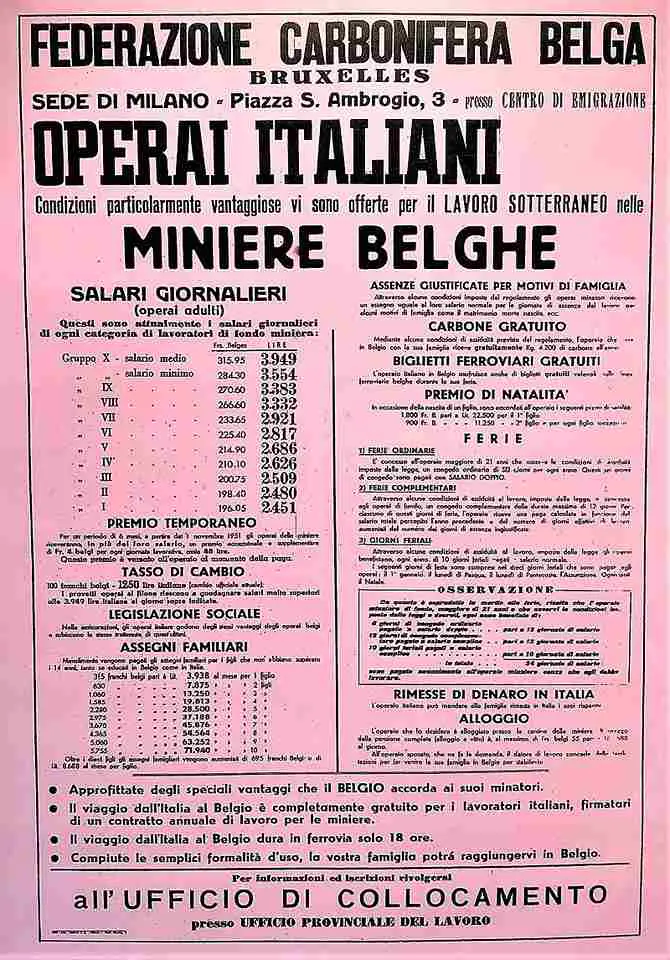

The ‘Men for Coal’ agreement

At that time, many Italians moved to Belgium to work in coal mines. This migration was driven by the “Italian-Belgian Protocol,” signed in Rome on June 23, 1946, and updated on April 26, 1947.

The agreement planned to send 50,000 Italian miners to Belgium at a rate of 2,000 per week. In return, Belgium agreed to sell at least 2,500 tonnes of coal to Italy monthly for every 1,000 miners sent.

This arrangement was known as “Men for Coal.” Miners had to commit to five years of work, with at least one year mandatory under penalty of arrest.

The Italian workers had to pass medical exams, sign contracts, and be assigned to various mines. They received training, housing, and social services but were paid less than Belgian miners.

This deal helped reduce unemployment and secure energy for Italy while boosting coal production in Belgium, which had declined by 40% during the war. It also strengthened Belgium’s ties with Italy, which was seen as a potential ally against communism.

With the end of the war, all prisoners were repatriated, leaving Belgium in need of a new mining workforce. The local Belgian population, strongly unionized and aware of the horrific working conditions, was not a viable source of labor. Consequently, Belgium sought workers from abroad.

Italy, in the immediate post-war period, faced political and social turmoil along with rampant unemployment. Anne Morelli, a Belgian-Italian historian and honorary professor at the Free University of Brussels (VUB), explained, “Italy was very happy to get rid of young Italians looking for jobs that weren’t available, especially if they were anarchists, socialists, or communists.”

Horrific working and living conditions

When Italian miners arrived in Belgium, they found themselves in terrible living conditions. They were housed in old concentration camps with wooden barracks, bunk beds, straw mattresses, and dirty linen.

Furthermore, the working conditions were horrific. In the coal mines, Italian workers faced long hours, cold temperatures, dust, noise, and constant danger.

However, workers’ rights were still lacking. Illnesses like silicosis, caused by inhaling silica dust, were common but not recognized as occupational diseases.

Italians in Belgium faced heavy risks. Children fell ill in the camps, where there was often no clean water. Between 1946 and 1955, around 500 Italians died in Belgian mines, with many more suffering from long-term health issues.

Lorena Noé, daughter of an Italian miner, shared, “My father worked for 15 years straight in the mines and then slowly fell ill. He grew weaker and began to lose his breath. His health continued to decline throughout the seventies, and he had to frequently go to the hospital. At home, he had an oxygen tank. “For us children, it wasn’t easy hearing him cough all night, and it destroyed us to see that he couldn’t breathe,” she added.

Italian miners also faced discrimination from locals who saw them as competitors for jobs. They had to endure harsh treatment and social marginalization.

Private rentals were scarce, and landlords often refused to rent to Italians. Nunzio also recalled living in tin shacks, with water dripping on their heads. Italians were called “dirty macaroni” and “sandwich thieves.”

Many Italians felt isolated and nostalgic for their homeland. Some hoped to return to Italy, while others brought their families to Belgium, forming the first Italian communities.

Some new arrivals were so shocked by the conditions that they refused to work. They were imprisoned and deported. But for most, there was no choice. “Back in Italy, we died of hunger,” said Nunzio, an ex-miner. “The only option was to leave.”

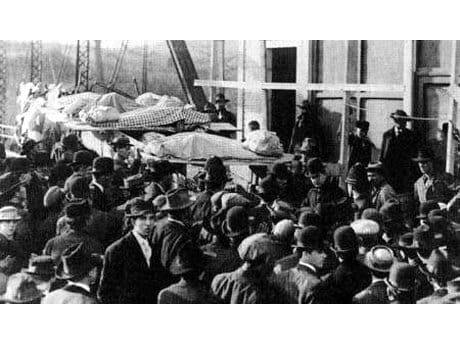

The “Men for Coal” agreement with Italy ended in 1956 after the Marcinelle mining disaster, which killed 262 workers, including 136 Italians.

The disaster hit Italy hard, especially because many victims came from the same regions. The village of Manoppello in Abruzzo was the hardest hit, losing 22 men. Similar tragedies affected villages in Calabria, Sicily, and other parts of southern Italy, leaving many widows and children.

After Italy ended the migration agreement, Belgium sought workers from Spain, Greece, Morocco, and Turkey. Strikes occurred as miners recognized the severe risks they faced.

A commission’s report left many questions unanswered, and in 1961, only one engineer, Adolphe Calicis, was sentenced to six months for negligence. Safety failures, such as inadequate training, poor rescue equipment, and insufficient insurance, remained unaddressed. Victims’ families waited eight years for a small compensation of 5,000 Belgian francs.

Following the disaster, Belgium established a Mines Safety Commission in September 1956 to monitor and improve safety procedures. The High Authority of the European Coal and Steel Community, the forerunner of the EU, also took greater control over mine safety, leading to improved conditions in Belgian and European mines.