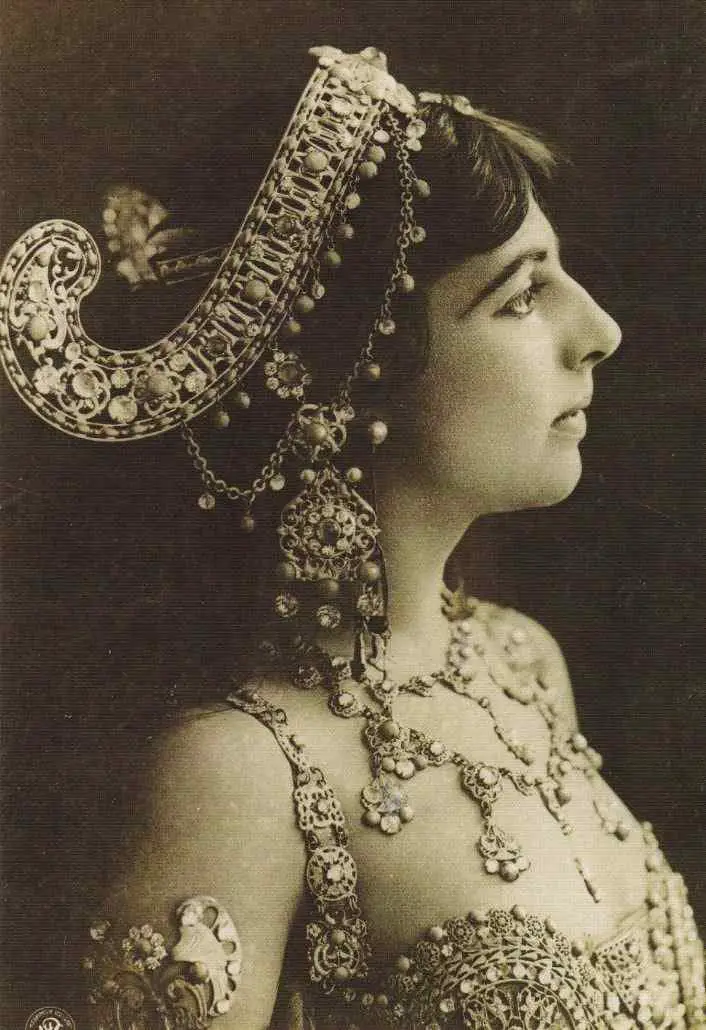

Dutch dancer Mata Hari, perhaps Europe’s most famous striptease performer, was executed by a French firing squad after being convicted of espionage for the Germans during World War I.

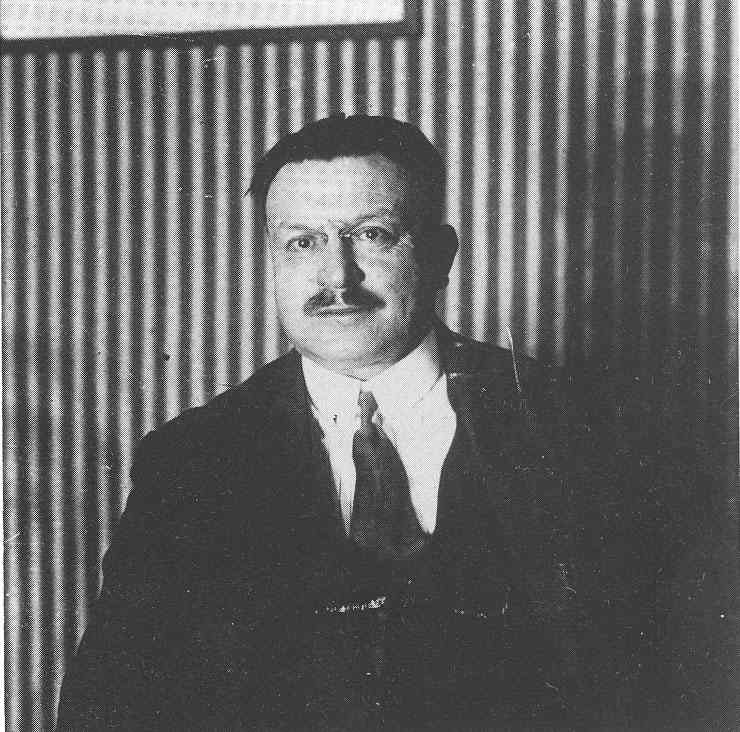

Her real crime, however, was being a lady with loose morals. Her arresting officer observed, “She was one of the most charming specimens of female humanity I had ever set eyes on,” while Sir Basil Thomson, Assistant Commissioner of Police and head of Special Branch, remembered her as “tall and sinuous, with glowing black eyes and a dusky complexion, vivacious in manner, intelligent and quick in repartee.”

Known for her charm and intelligence, Mata Hari’s real life was just as intriguing.

Mata Hari’s Early Life and Marriage

Born Margaretha Geertruida Zelle on August 7, 1876, in Leeuwarden, Netherlands. She had a happy early childhood as her father was a successful haberdasher.

But things changed when her father was bankrupt, and her parents divorced. When her mother died in 1891, Margaretha’s world fractured completely, forcing her to live with various relatives, drifting from one household to another.

When Margaretha was eighteen, she came across an advertisement by Capt. Rudolf MacLeod, twice her age. He was home on leave from the Dutch East Indies seeking “a girl of pleasant character—object matrimony.” Eager for adventure, she decided to respond.

The couple didn’t waste any time and got engaged just six days later. On July 11, 1895, they were married at the city hall of Amsterdam. However, the marriage was neither happy nor long-lasting. MacLeod drank heavily, cheated on Margaretha, and beat her.

Their son died in 1899, adding more strain to their troubled marriage. There are several theories that he was poisoned by a maid. After seven hard years, she finally left him.

After losing custody of her daughter to her ex-husband, Margaretha decided to start anew in Paris. She once told an interviewer why she left Holland for Paris in 1902, “I thought all women who ran away from their husbands went to Paris.”

The Journey to the “Star of Dance”

In 1903, Margaretha first worked as a riding instructor after coming to the City of Lights. Then, her owner introduced her as a dancer to the salons of one of Paris’ upper-class doyennes.

No classical dance training and too tall to pass as a ballerina, she understood she needed an angle to distinguish herself as more than a typical dance-hall girl.

Aware that her strength lay in her sex appeal rather than her dance skills, Mata Hari used her allure to captivate audiences. Drawing inspiration from her time in the Indies, she adopted the stage name “Mata Hari,” derived from the Malay words for “eye” and “day,” meaning “Eye of the Day” or the sun.

In February 1905, Mata Hari debuted in an exclusive Paris salon. Her dance presented as a sacred invocation to Shiva, the Hindu god of destruction, mixed raw eroticism with a guise of spirituality.

She wore a costume she designed herself, featuring diaphanous veils, a metallic brassière, and jewel-adorned cache-siens. She gradually removed each piece, intensifying the performance until, at the climactic moment, she prostrated herself almost completely naked at the god’s feet.

Her career was made, as a respected reviewer wrote breathlessly in a society magazine: “Lady MacLeod is Venus.”

Declared a “Star of Dance” in 1908, the olive-skinned beauty spent the next several years traveling across Europe, performing before sold-out crowds. She also began numerous affairs with military officers and wealthy aristocrats, who lavished her with gifts and money.

“Tonight I dine with Count A and tomorrow with Duke B,” she once quipped. “If I don’t have to dance, I make a trip with Marquis C. I avoid serious liaisons.”

However, during the First World War, Mata Hari’s reputation started to decline and financial pressures mounted.

The Netherlands stayed neutral in the conflict, and being Dutch, Mata Hari could move between countries without restrictions. However, her movements drew attention wherever she went.

When she attempted to return to France, German authorities seized her belongings and assets, forcing her to return to her native Holland. She rekindled an old affair with a wealthy Dutch baron there, but the financial strain remained.

Mata Hari’s Entanglement in Espionage

In 1915, Karl Kroemer, the honorary German consul in Amsterdam, approached her with an offer. He offered her 20,000 francs for pillow talk with French officers. “More, if it proves valuable,” he added. “Then, you can have all you want.”

Struggling financially, Mata Hari accepted the offer, though her actual involvement in espionage remains ambiguous. She was assigned the codename “H 21” and continued her travels across Europe, maintaining relationships with influential men.

Her movements and associations soon attracted the attention of British intelligence, which suspected her of espionage.

British agents in Holland alerted the French: “She is regarded by Police and Military to be not above suspicion, and her subsequent movements should be watched.”

In 1916, French intelligence officer Georges Ladoux saw an opportunity to either entrap or recruit her. “Only promise me,” he said, “that you will not seduce any French officers.”

“I ask a million gold francs,” she told him. “I’ve no intention of hanging around for months getting tidbits of information. I’ll bring off one big coup, and then go.”

She intended to reconnect with German intelligence and gradually work her way back into the inner circles of the High Command, leveraging personal relationships along the way.

“I have already been the mistress of the Crown Prince, and it would be up to me if I wanted to see him again…. Here, I am just a lady of the night; there, I was treated as a queen.”

“Go to Holland,” Ladoux told her, “and you will receive my instructions.”

However, her efforts to travel were not successful. At Scotland Yard, she was interrogated by Sir Basil.

“We were convinced now that she was acting for the Germans,” he wrote, “and that she was then on her way to Germany with information which she had committed to memory.”

Mata Hari claimed she was a spy but for the French, with Ladoux as her controller. He informed the British that he had hired her purely as a ruse to trap her. With a complete lack of evidence, Mata Hari was released again—this time back to Spain, rather than Holland.

Following that, Mata Hari wound up in neutral Spain, where she bedded a German major called Arnold Kalle. What happened between the two is widely debated.

Though it’s possible that Kalle sent the telegrams in an antiquated code that the Germans knew the Allies had deciphered as a ruse to expose her, they provided Ladoux with all the proof he needed.

Mata Hari was taken into custody on February 13, 1917, accused of spying, and imprisoned at the notorious Saint-Lazare prison in Paris.

The dancer was questioned for several months after spending time in her wet, vermin-infested cage. She spoke openly about her promiscuous lifestyle, but she insisted that she had never been an espionage agent for a nation other than France. “A courtesan, I admit it,” she said. “A spy, never!”

When questioned about Kalle’s messages, she admitted to taking money from the Germans, but she denied giving them any secrets. She said, “I never considered myself a German agent with a number because I never did anything for them.”

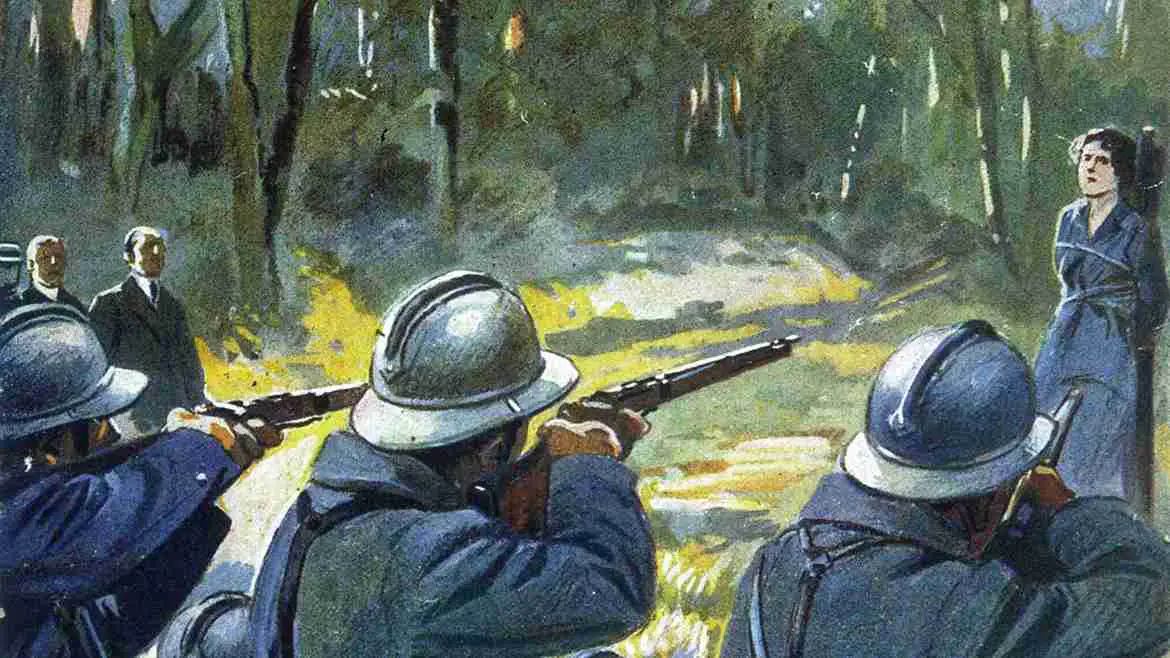

Mata Hari’s Execution by Firing Squad

On February 13, 1917, Mata Hari was arrested in her room at the Hotel Elysée Palace on the Champs Elysées in Paris. She faced trial on July 24, accused of espionage for Germany and allegedly responsible for the deaths of over 50,000 soldiers.

Despite suspicions from both French and British intelligence, neither could provide concrete evidence to support the charges against her.

Mata Hari was convicted of espionage and sentenced to death by a firing squad. At dawn on October 15, 1917, Mata Hari was led to a field on the outskirts of Paris.

According to an eyewitness account by British reporter Henry Wales, she refused a blindfold and blew the firing squad a kiss.

A 1934 New Yorker article described Mata Hari at her execution wearing “a neat Amazonian tailored suit and new white gloves.”

Another account claimed she wore a suit, low-cut blouse, and tricorn hat chosen by her accusers for her trial, as it was her only clean outfit in prison.

Wales documented her death, noting that after the shots, “Slowly, inertly, she settled to her knees, her head up always, and without the slightest change of expression on her face. For the fraction of a second it seemed she tottered there, on her knees, gazing directly at those who had taken her life. Then she fell backward, bending at the waist, with her legs doubled up beneath her.”

A non-commissioned officer then shot her in the head to ensure her death.

The Debate over Mata Hari’s Guilt

The question of Mata Hari’s guilt remains a topic of debate among historians for many years.

Some believe she was a scapegoat used to boost French morale during a bleak war period, while others argue that her disregard for societal norms and her numerous liaisons with influential men made her an easy target for accusations of espionage.

While called “the greatest woman spy of the century,” Margaretha’s actual espionage activities are unclear and often exaggerated because of her personality and lifestyle.

In 1930, the German government exonerated her, acknowledging the lack of concrete evidence against her. Subsequent releases of French documents in 2017 further fueled the belief that Mata Hari was wrongfully convicted.

Her glamorous life has left many historians guessing wildly. Even after her death, Margaretha Geertruida Zelle remains an enigmatic figure, her fame continuing to captivate people worldwide.